This SimCity-Like Tool Lets Urban Planners See The Potential Impact Of Their Ideas

Urban Footprint makes it easy to run simulations to see how a new plan might change traffic and commute times, the ability of kids to walk to school, access to jobs, energy use, the local economy, health, and carbon emissions.

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]

Editor's Note: What about the infrastructure capacity of water, sewer, roads, schools, tunnels and bridges? Planners have big ideas but don't like to actually plan for these boring considerations. This is why many of us are strongly opposed to Plan Bay Area, SB827 and other rapid urbanization schemes.

BY ADELE PETERS6 MINUTE READ

When a state senator in California proposed a bill that would require cities to allow developers to build dense housing near transit stops–including five-story apartment buildings on some streets where there are only one or two-story buildings now–Californians quickly took sides. Some say the change is a needed step to address the state’s housing crisis, and that it would lower carbon emissions because people living near transit would no longer have to drive. Some say that it would change neighborhood character, or that the increased development will drive displacement of low-income renters.

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]

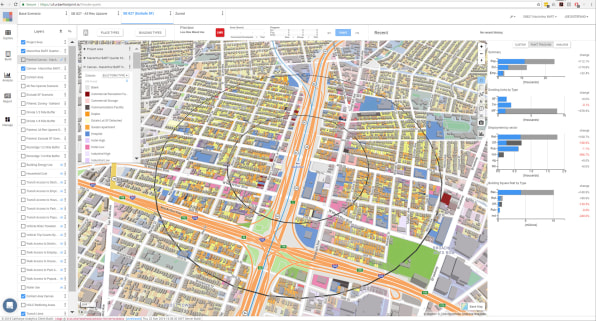

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]One thing that’s helpful–but often lacking–in arguments across the country about major urban policy like this is specific numbers about how the change might affect the city in the future. UrbanFootprint, a startup with a software tool of the same name, was first to begin providing stats. Near one Oakland BART station, for example, they found that the surrounding area could go from 4,447 housing units to 27,156. In comparison to building the same amount of housing in a typical Alameda County location, they later calculated, the dense housing near the BART station would result in 270 million fewer miles traveled in cars per year, 12 million fewer gallons of fuel burned (a savings of $43 million in fuel cost alone), and nearly 110,000 metric tons of carbon emissions averted.[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]

The software makes it possible to plug in any urban planning scenario, push a few buttons, and see a broad set of impacts, including how a plan might change traffic and commute times, the ability of kids to walk to school, access to jobs, energy use, the local economy, health, and carbon emissions. (The software tool can’t predict changes to rents). In the past, these types of complex calculations–if they were done at all–could take months or years as teams of consultants gathered massive amounts of data and made or customized models. Today, the State of California announced that it is partnering with the company to make the tool available for free to more than 500 cities, counties, and regional agencies in the state.

When communities can see comprehensive data about multiple plans for the future, the startup’s founders say, it becomes easier to compare them and reach consensus. For planners and designers, the tool can lead to better designs.

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]Co-founders Peter Calthorpe and Joe DiStefano first started using data in a similar way–without the software–around 25 years ago. As they had worked with cities as consultants, they’d seen information gaps. “Whether it was a decision about how to invest in transportation or a decision about where and how to put housing, battles about sprawl versus transit-oriented development, all this stuff was being done in a next-to-factless vacuum,” says DiStefano.

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]Co-founders Peter Calthorpe and Joe DiStefano first started using data in a similar way–without the software–around 25 years ago. As they had worked with cities as consultants, they’d seen information gaps. “Whether it was a decision about how to invest in transportation or a decision about where and how to put housing, battles about sprawl versus transit-oriented development, all this stuff was being done in a next-to-factless vacuum,” says DiStefano.In Salt Lake City, in the late 1990s, they worked with the city to envision how it could meet a new demand for housing. Environmentalists were concerned about sprawl. Fiscally conservative legislators were concerned about the cost of water for new neighborhoods. The Mormon Church wanted affordable housing. Calthorpe and DiStefano ran the numbers for the various scenarios that each group wanted. When everyone saw the results, they collectively chose the option of transit-oriented development.

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]“When you lay out all the facts against all the scenarios what happens is there are few really truly virtuous strategies that rise up and solve many problems simultaneously,” says Calthorpe. “And when you find those strategies you get a political consensus that didn’t exist before.”

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]“When you lay out all the facts against all the scenarios what happens is there are few really truly virtuous strategies that rise up and solve many problems simultaneously,” says Calthorpe. “And when you find those strategies you get a political consensus that didn’t exist before.”This happens, he says, despite living in a time when facts sometimes don’t seem to matter. The process doesn’t ask environmentalists or fiscal conservatives to change their values; it shows which solutions can best meet a variety of desires.

Looking at several impacts of a plan simultaneously also makes connections between multiple problems clearer, such as the link between walkable neighborhoods, transit, and health. “We tend to deal with our issues one at a time,” says Calthorpe. “If it’s obesity, we think about diet and exercise. But actually, the kind of environments we create have a huge impact.”

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]They used a similar process in Portland, Oregon, post-Katrina Louisiana, China, and elsewhere. In Hawaii, the local Sierra Club opposed a new transit system, but the group changed its mind after seeing the data about the reductions in car trips the project would bring. The process worked. But Calthorpe and DiStefano also realized that it was difficult to scale. The work in Salt Lake City took two years, a massive budget, and “an army of consultants.” They started to play with the idea of creating software that could make the process cheaper, quicker, and more accessible.

When California passed a 2008 law that required cities and regions to create plans for more sustainable design to reduce emissions, the state needed software to set targets and measure compliance. The government asked Calthorpe and DiStefano to take its early version of the software and develop it further. The tool helped the state see a range of financial, environmental, and social impacts beyond carbon, helping win broader support for smart growth rather than climate action alone. Seeing that success, UrbanFootprint decided to make another version that any city can use.

In late 2017, the company raised $5 million in seed funding from the venture firm Social Capital and angel investors. Social Capital, a purpose-driven firm in Silicon Valley, has a different perspective than some peers. “We believe UrbanFootprint will be transformative for one of the most critical real-world challenges of our times,” says Jay Zaveri, a partner at Social Capital. “It sits at the nexus of software technology, machine learning, and urban infrastructure scenario planning to drive sustainable and equitable outcomes for cities everywhere.”

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]

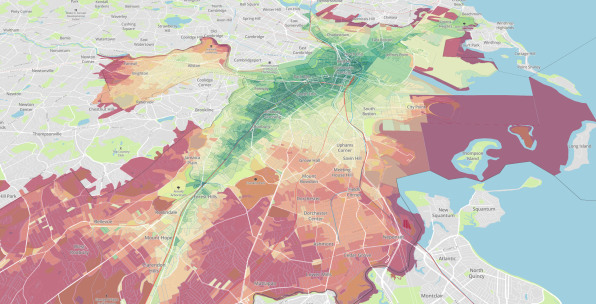

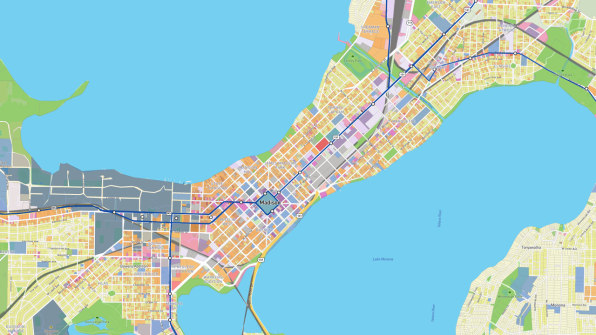

[Image: courtesy UrbanFootprint]The tool pulls in data from around 100 datasets–about jobs and the people living in a neighborhood, how many people are driving or biking, existing buildings, predictions for sea levels rise, decaying infrastructure, inequality, health, and more–and uses machine learning to clean up the data. When someone using the software enters information about a proposed plan or policy, the tool feeds back environmental, social, and economic metrics. The tool uses a variety of models, some built in-house, and others that build on academic work. California energy and water agencies helped build the models for measuring energy and water impacts; conservation modeling was developed with the Nature Conservancy. After entering data about a proposed plan, a city can see detailed, color-coded maps that show, for example, access to public transit.

As new data becomes available from the growing range of sensors used by city governments or from startups like Aclima, which is using air quality sensors attached to Google StreetView cars, that can be added to the tool. UrbanFootprint worked with The Nature Conservancy to add data about conservation and ecosystem services, and with the American Lung Association to add data about air quality impacts like asthma.

“The data is getting to the point now where one of the biggest challenges for people engaged in city building is filtering through it all,” Calthorpe says. “It turns into an avalanche of information that people can’t really manage their way to clarity and insights.” It isn’t really useful, he argues, unless it’s in a tool that makes it easily accessible.

The software is currently built for the U.S., though UrbanFootprint is also working with international cities like Chongqing, China, which has a population of 30 million, nearly as large as all of California. They believe it can be useful anywhere, and as cities continue to grow–by 2050, 70% of the world’s population will be urban–good planning, which shapes social opportunity and environmental impact, is also necessary.

“In China alone, they’re going to be building cities for another 300 million people in the next 20 years,” says Calthorpe. “That’s basically building the urban environment of the United States. And they’re going to do that in 20 years instead of 200 years. So getting cities right is really at the crux of the well-being of mankind.”

No comments:

Post a Comment