Brief video with the protestors outside the Citizen Marin Town Hall on March 20, 2013. The Town Hall event was open to the community to talk about affordable housing solutions. People from all perspectives were encouraged to speak up about their views on affordable housing.

This group of activists were organized by Cesar Lagleva, a Marin Profesional Public Employee Union Shop Steward (M.A.P.E.) encouraged others to protest against the public event. Their cries of Racism, NIMBYism and Classism are meant to intimidate people from speaking openly about housing. The irony is that most people inside at the event SUPPORT a fair allocation of affordable housing provided it is financially responsible and fits in to existing neighborhood densities.

Cesar was author of the highly offensive Marin Voice article I mentioned in an earlier post here.

Also present was the every present protestor and self proclaimed "Janitor of Political Waste Management", Jimmy Fishbob Geraghty. His daily rants about "racist Marinites" can be found on the San Rafael Patch and Marin IJ online. You will often see him holding signs and protesting around the Bay Area. If you can't get enough of him on the public news sites, you can get the full rants on his facebook page. After this footage was shot, I spoke with him briefly, and came away with a positive impression of him. He seems earnest but misguided and genuinely a nice guy. It was one of my personal highpoints of the evening.

Local affordable housing lobbyist, Dave Coury, also was present wearing his button to end Racism, Nimbyism and Classism. He had been overheard at the February 2013 planning meeting asking for "affirmative action complaints against the Dixie School district" on his cell phone in the lobby during testimony about the Housing Element and its effects on school funding for Dixie School District. He also has publicly called on the supervisors to simply zone all land in Marin within 1/2 mile of 101 Freeway as 30 units per acre multifamily housing. We can only guess his client list funding his activities. In the July 9, 2013 Board of Supervisors meeting, Dave Coury called the struggle for housing in Marin ""a war" and linked a shooting in Marin City to the housing issue.

Local affordable housing lobbyist, Dave Coury, also was present wearing his button to end Racism, Nimbyism and Classism. He had been overheard at the February 2013 planning meeting asking for "affirmative action complaints against the Dixie School district" on his cell phone in the lobby during testimony about the Housing Element and its effects on school funding for Dixie School District. He also has publicly called on the supervisors to simply zone all land in Marin within 1/2 mile of 101 Freeway as 30 units per acre multifamily housing. We can only guess his client list funding his activities. In the July 9, 2013 Board of Supervisors meeting, Dave Coury called the struggle for housing in Marin ""a war" and linked a shooting in Marin City to the housing issue.

Cesar Lagleva, sat next to me at a One Bay Area Plan meeting on April 16th. I greeted him and offered to shake his hand and he shot back "don't touch me". Clearly, we have a ways to go on our friendship.

Cesar Lagleva, is one of the organizers for Concerned Marinites to End Nimbyism (CMEN ..no jokes please) and their website is http://www.concernedmarinites.org/. where you will find more of their rhetoric. It is amazing to me that this public employee union official attacks the taxpayers that support him with such language I am told he is a clinical social worker or psychologist. Here is a puff piece put out by his union.

Supervisor Steve Kinsey was the keynote speaker. He thanked M.A.P.E. for organizing and told the crowd that "Marin can be very unwelcoming". Like the rest of the crowd gathered, he was invited to participate the open town hall inside and share his views. Supervisor Kinsey did not attend but stopped for a TV news interview, got in his car and sped off.

We think a fruitful discussion about affordable housing will begin with honest, open dialog and not with shouts of RACISM, CLASSISM and NIMBYism.

We still have time to talk and my offer for a cup of coffee to share with Cesar is still open.

We still have time to talk and my offer for a cup of coffee to share with Cesar is still open.

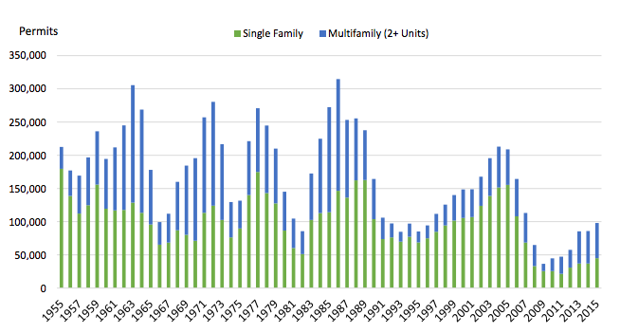

In a state where vacant homes and apartments are scarce and where rents and house prices are out of control, state leaders and experts have proposed a host of solutions. Build more homes, build them in higher-density developments and build them in existing cities and suburbs, closer to jobs, buses and commuter rail line. (Jeff Gritchen, Orange County Register)

In a state where vacant homes and apartments are scarce and where rents and house prices are out of control, state leaders and experts have proposed a host of solutions. Build more homes, build them in higher-density developments and build them in existing cities and suburbs, closer to jobs, buses and commuter rail line. (Jeff Gritchen, Orange County Register)