A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Why politicians love cities

Glenn Reynolds: Why politicians love cities

Glenn Harlan Reynolds 4:02 AM. EST June 21, 2016The 20th century French architect Le Corbusier, famous for his huge, inhuman structures, dedicated his first book To Authority. Too many of his successors seem to feel the same way. Now, in his new book The Human City: Urbanism For The Rest Of Us, Joel Kotkin says there’s a better way.

Today’s urban planners seem to favor high density. Like Le Corbusier, they’d like people to live in tall, densely packed buildings, take mass transit to work, and scorn the “fatter and slower and dumber” residents of the suburb, to use a description from Seattle’s The Stranger that Kotkin quotes.

The problem is that most people, especially people who have or want to have children, don’t like living that way, and that as American cities have become taller and denser, they have essentially become playgrounds for the rich and childless. “For all their impressive achievements, and sometimes inspiring architecture, high-density cores such as those in Manhattan, Seattle, San Francisco, Boston and Washington, D.C., have the lowest percentages of children,” Kotkin says in his new book.

And it’s not just in America. Kotkin says big Asian cities have the lowest fertility rates on the planet, and in Hong Kong, 45% of couples say they’ve given up on having children. Yet politicians love these cities.

As Kotkin writes, “Around the world, planners, politicians and pundits often wax poetic about these massive new building projects and soaring residences made up of hundreds of tiny stacked units, but there’s just one problem with this brave new condensed world: Most people, including many inner-city residents, aren’t crazy about it. People care deeply about where they live, and they often aren’t thrilled with the kind of urban vision held by many city leaders.”

So if people are lukewarm, why are politicians so enthusiastic about big urban development? I think there are three reasons: Snobbery, graft and politics.

The snobbery comes from the fact that most media are headquartered in big cities and the people who work there are the kind of people who like big cities — often people who, as one of Taylor Swift’s songs has it, move to a “big ole city” in part as revenge on the places they come from. As Kotkin notes, the writers, pundits and academic types who write on the subject of cities tend to live in big cities; suburban and rural people are treated as losers, or just ignored, despite the fact that most people don’t live in big cities. And there’s a class thing going on, too. As Robert Bruegmann noted in his book, Sprawl: A Compact History, nobody minds when rich people build houses in the country. It’s when the middle class does it that we get complaints.

The graft is probably more important still: Big developments mean lots of permissions, many regulatory interactions and, of course, big budgets — all of which lend themselves to facilitating the transfer of money from developers to politicians. Frequently they’re government subsidized, which allows that money to come, ultimately but almost invisibly, from the pockets of taxpayers.

(This is also why politicians like subways and light rail better than buses. You can reward a developer over the long term by putting a rail station near a development, which makes it a proper object for graft. Bus routes, on the other hand, can change overnight, so they’re not worth as much.)

Finally, there’s politics. Politicians like to pursue policies that encourage their political enemies to leave, while encouraging those who remain to vote for them. (This is known as “the Curley effect” after James Michael Curley, a former mayor of Boston.) People who have children, or plan to, tend to be more conservative, or at least more bourgeois, than those who do not. By encouraging high density and mass transit, urban politicians (who are almost always on the left) encourage people who might oppose them to “vote with their feet” and move to the suburbs.

This isn’t necessarily good for the cities they rule. Curley’s approach, which involved “wasteful redistribution to his poor Irish constituents and incendiary rhetoric to encourage richer citizens to emigrate from Boston,” as David Henderson wrote on the EconLog, shaped the electorate to his benefit. Result: “Boston as a consequence stagnated, but Curley kept winning elections.”

But that’s OK. Politicians don’t care about you. They care about power, in urban planning and in everything else.

Glenn Harlan Reynolds, a University of Tennessee law professor and the author of The New School: How the Information Age Will Save American Education from Itself, is a member of USA TODAY's Board of Contributors.

Saturday, December 30, 2017

"Housing Crisis" or bubble ?? California Net Migration -556,710

"Housing Crisis" or bubble ??

California Net Migration -556,710

"The latest population estimates indicate that the long-term movement to the South and West is continuing. Of course, the biggest exception in the West remains its largest state, California, which has become one of the nation's largest exporters of people since the 1990s."

http://www.newgeography.com/content/005837-the-migration-millions-2017-state-population-estimates

by Wendell Cox 12/30/2017

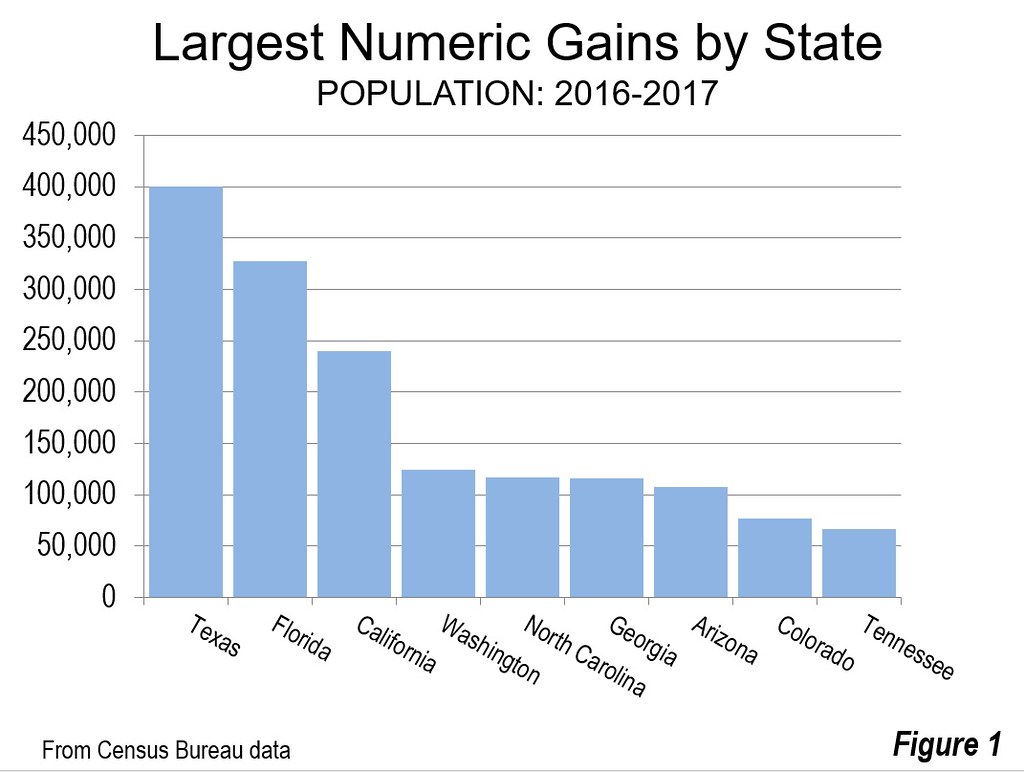

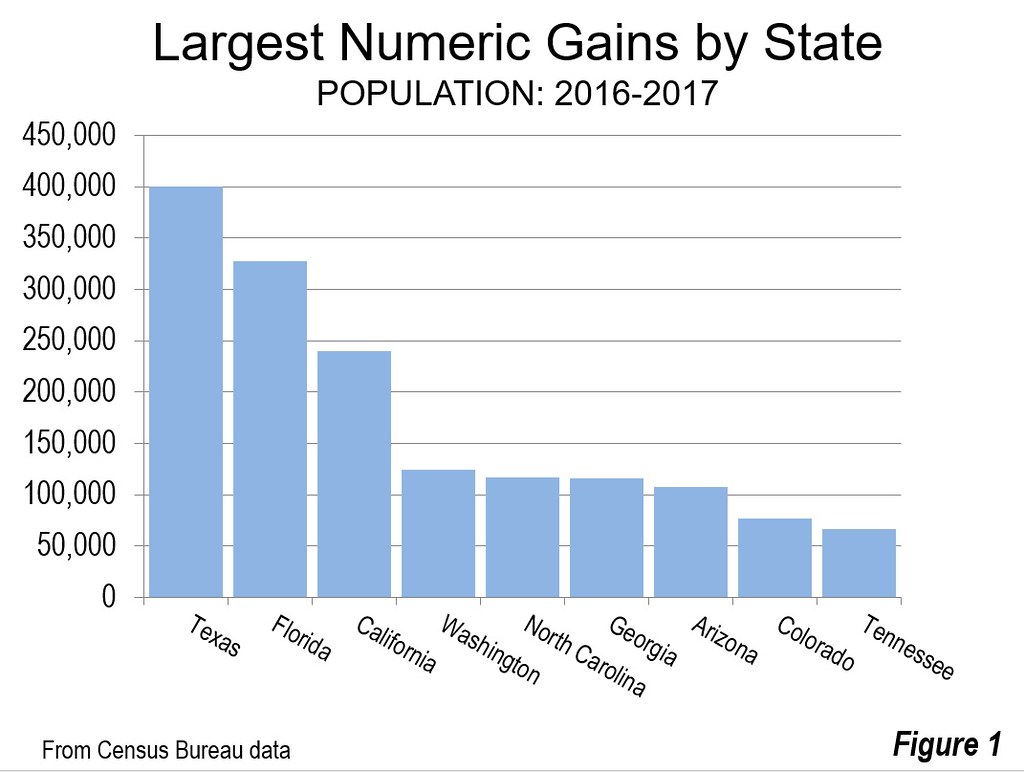

Texas added the most new residents of any state over the past year according to the July 1, 2017 estimates of the United States Census Bureau. Texas grew by 400,000 residents (Figure 1). Florida added 328,000 residents more than one third more than California. Four states grew between 100,000 to 125,000, led by Washington, North Carolina, Georgia and Arizona. Colorado and Tennessee round out the top 10. The ten states adding the most new residents include five from the South census region and five from the West census region.

Population Growth

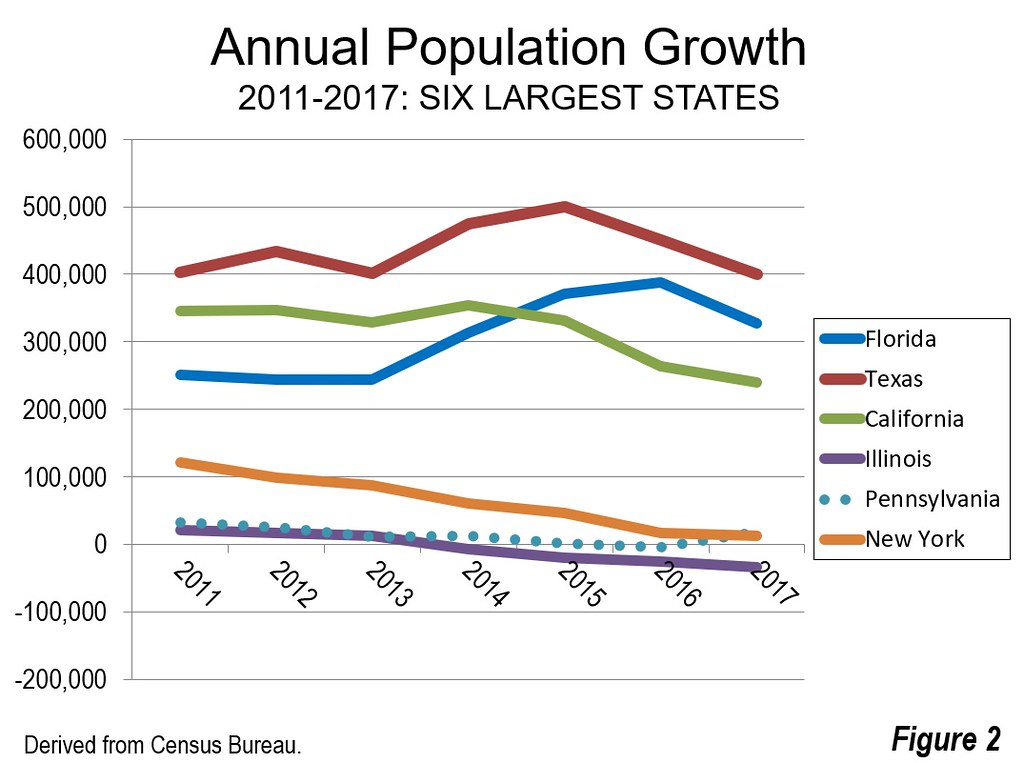

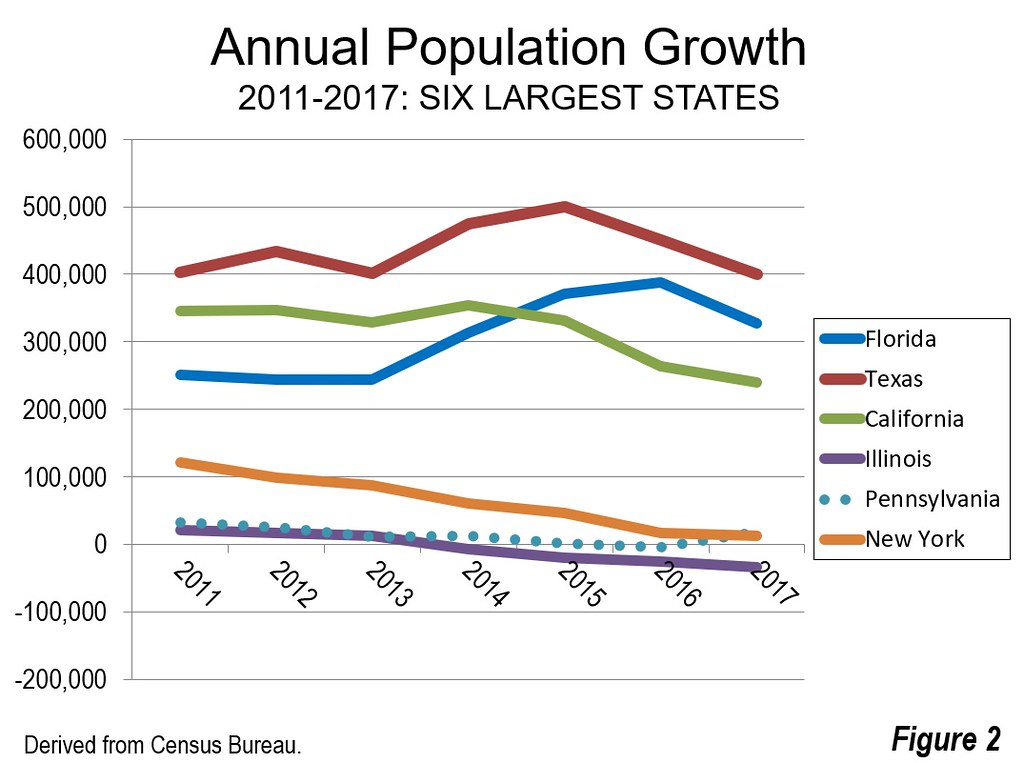

Over this decade, the three largest states have dominated numeric population growth. Texas has led the nation in each of the seven years, though has experienced declines in growth over the last two due likely to the instability in petroleum markets. Since 2010, Texas has added 3.1 million residents, more than live in 18 states and the District of Columbia. California has added 2.2 million new residents since 2010, edging out Florida. California's growth, however, has dropped significantly, to 240,000 between 2016 and 2017 the smallest number since the late 1990s. California's growth in this decade had peaked in 2014 at more than 350,000, but has since dropped by nearly one quarter. Florida added 2.1 million new residents and has led California in each of the last three years.

The other three largest states did much more poorly. New York has dropped from a gain of over 120,000 in 2011 to only 13,000 in 2017. Illinois has done even more poorly, dropping from the 21,000 gain in 2011 to a loss of 33,000 in 2017. Illinois has experienced a reduction in its growth each year of this decade.

Illinois Drops a Notch: Further, Illinois in 2017 lost its long standing hold on the fifth-largest position to Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania's ascendancy reverses a development in the 1950s, when Illinois passed Pennsylvania to become the third largest state. Less than a decade earlier, Pennsylvania had been passed by California, relinquishing its second ranking, which it had held since the 1810 census. Later, Illinois had been passed in the 1970s by Texas and in the following decade by Florida. (Figure 2).

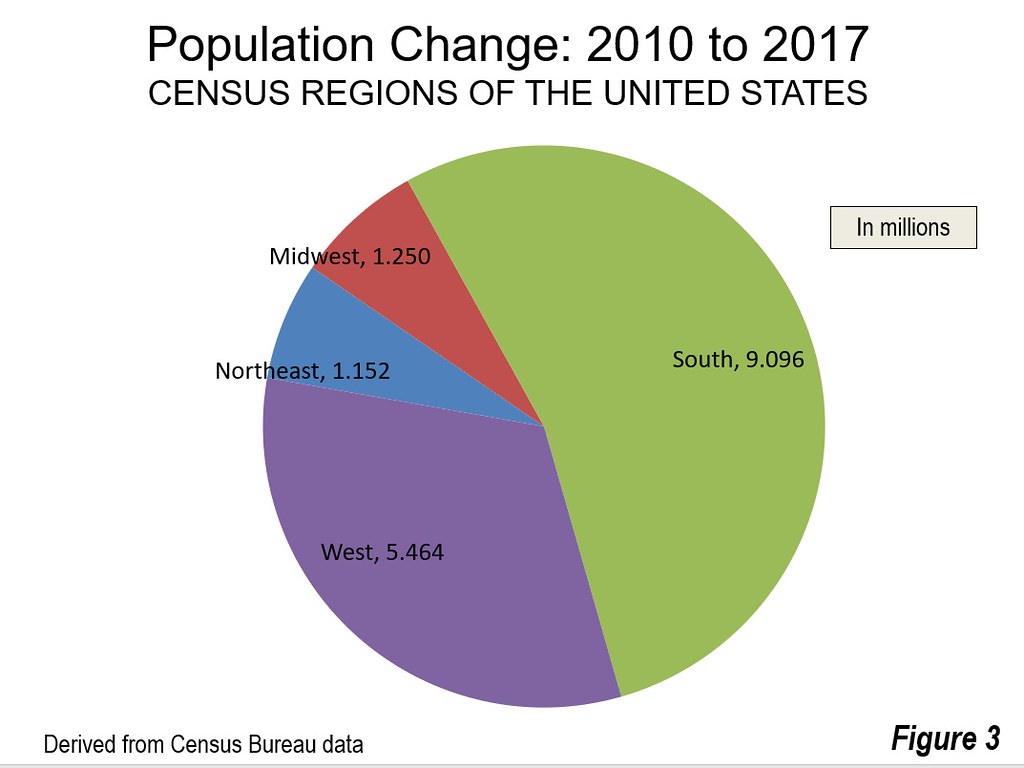

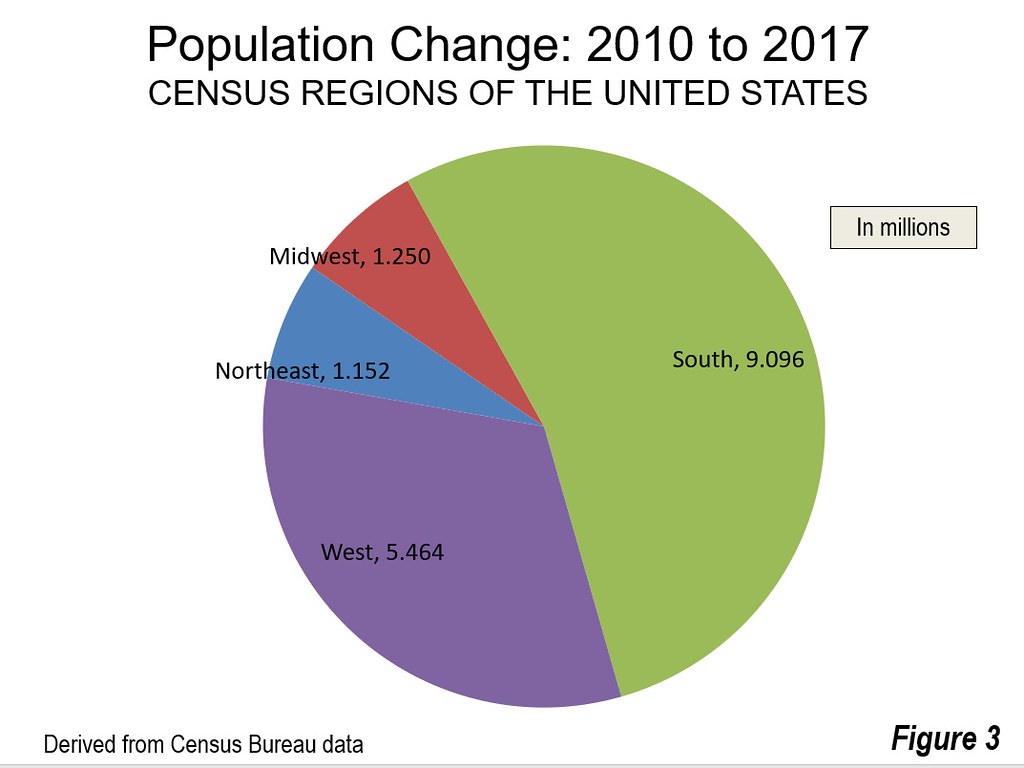

The South census region has dominated US population growth throughout the decade. Between 2010 and 2017, the South added 9.1 million new residents or 54% of the national growth. This compares to the West, which also grew strongly but added millions fewer (5.5 million new residents). The West accounted for 32% of the national growth. The Midwest and Northeast continue to lag, each taking 7% of the national growth (Figure 3).

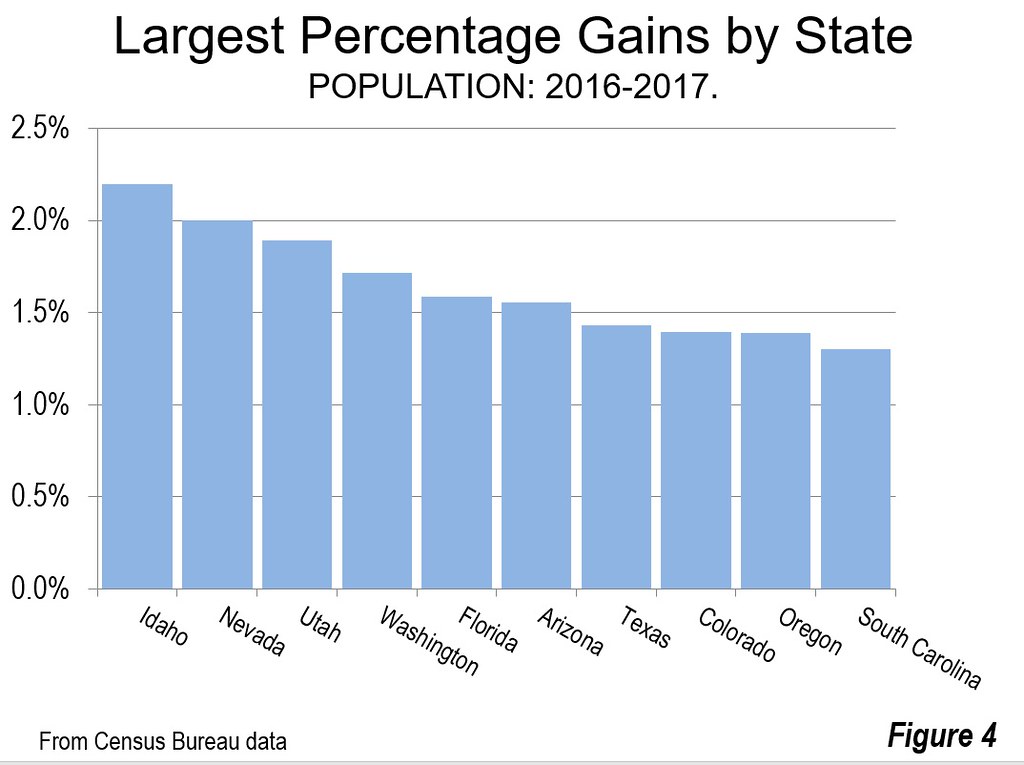

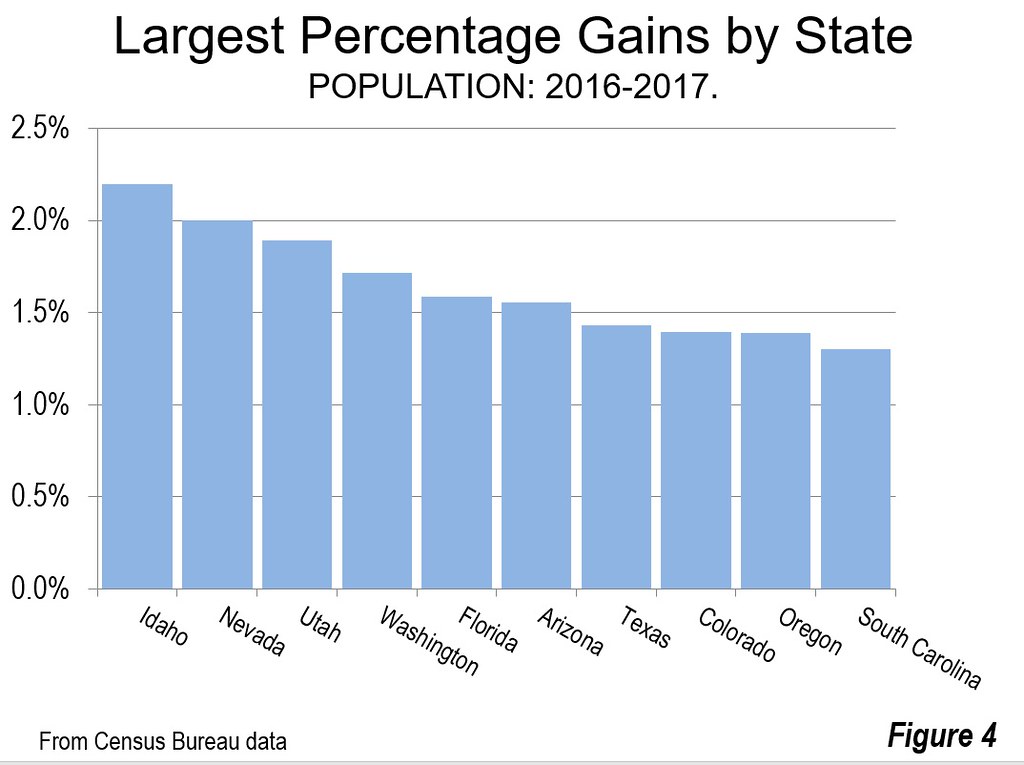

Idaho experienced the largest proportional growth rate in 2007, at 2.2%. Idaho was followed closely by its neighbors, Nevada at 2.0% and Utah at 1.9%. The next four positions were taken by large or medium sized states, including Washington at 1.7%, Florida and Arizona at 1.6% and Texas at 1.4%. Colorado and Oregon grew at 1.4%, followed by South Carolina at 1.3% (Figure 4).

Where the Millions are Moving

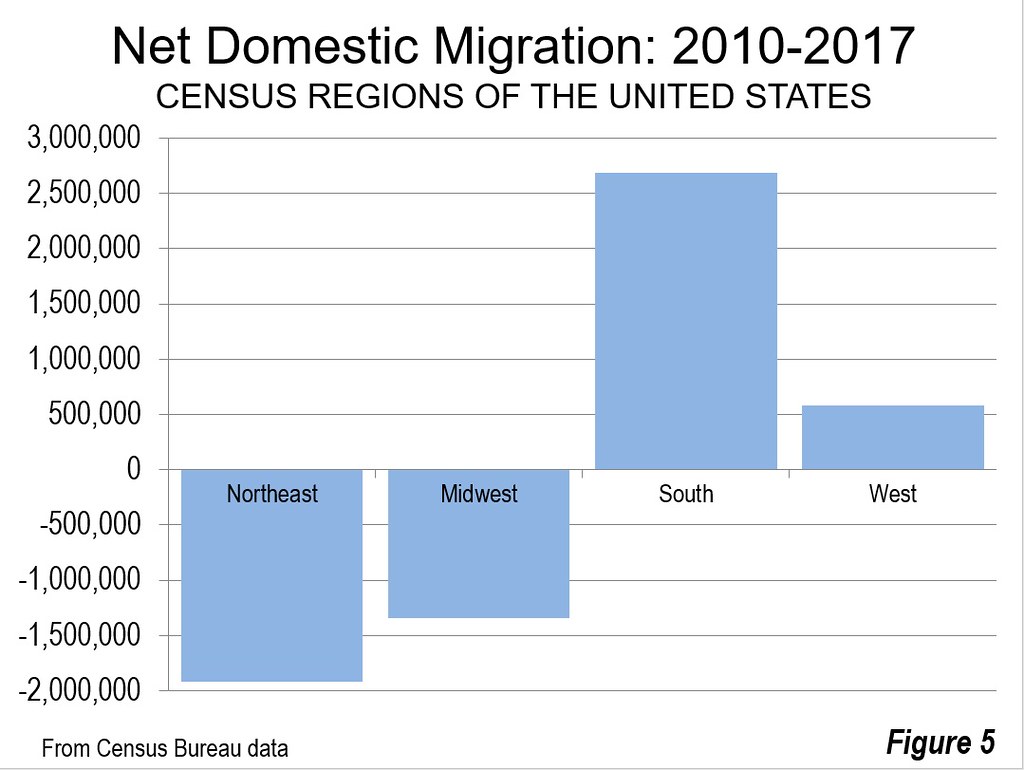

Despite the fact that interstate migration stands at a lower rate than in recent decades, millions of people continue to cross state lines seeking new residences. From 2010 to 2017, the number was 4.3 million. Domestic migration has been dominated by the South and West census regions, consistent with their dominance of population growth.

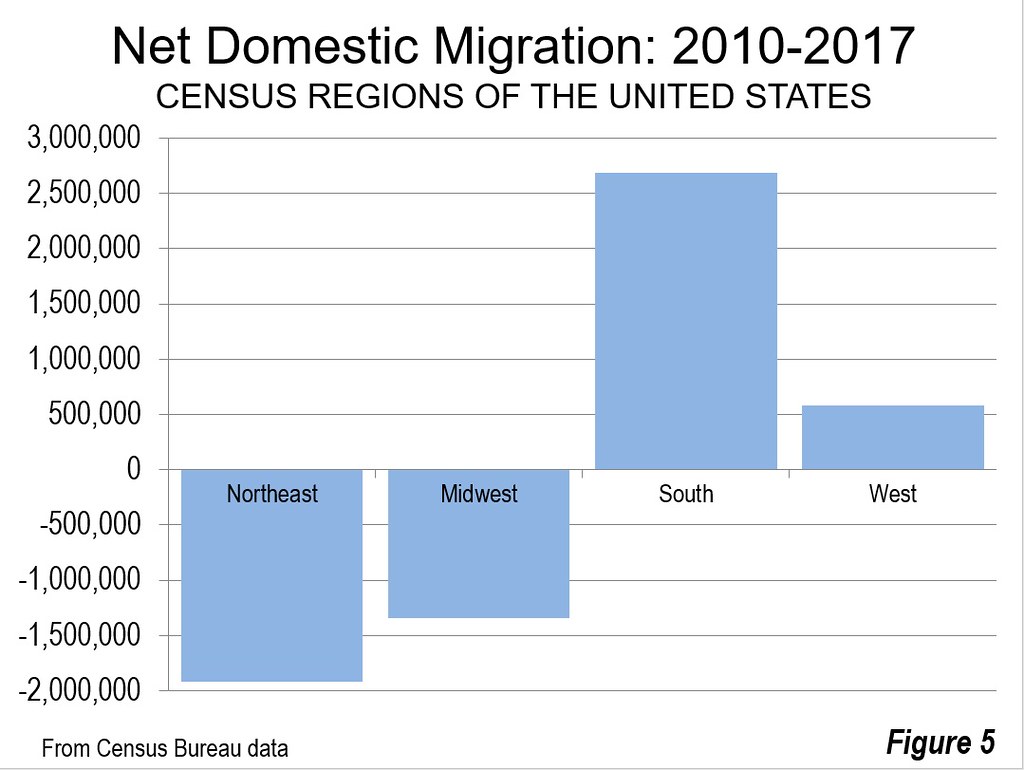

The South census region had a net domestic migration gain of 2.7 million residents. The West census region had a gain of 600,000 net domestic migrants, far short of the number in the South. In contrast, a net 1.9 million residents left the Northeast for other census regions, while 1.3 million left the Midwest for elsewhere (Figure 5). Even so, as indicated above, the Northeast and Midwest continue to grow as a result of in migration from other countries and natural growth (births minus deaths).

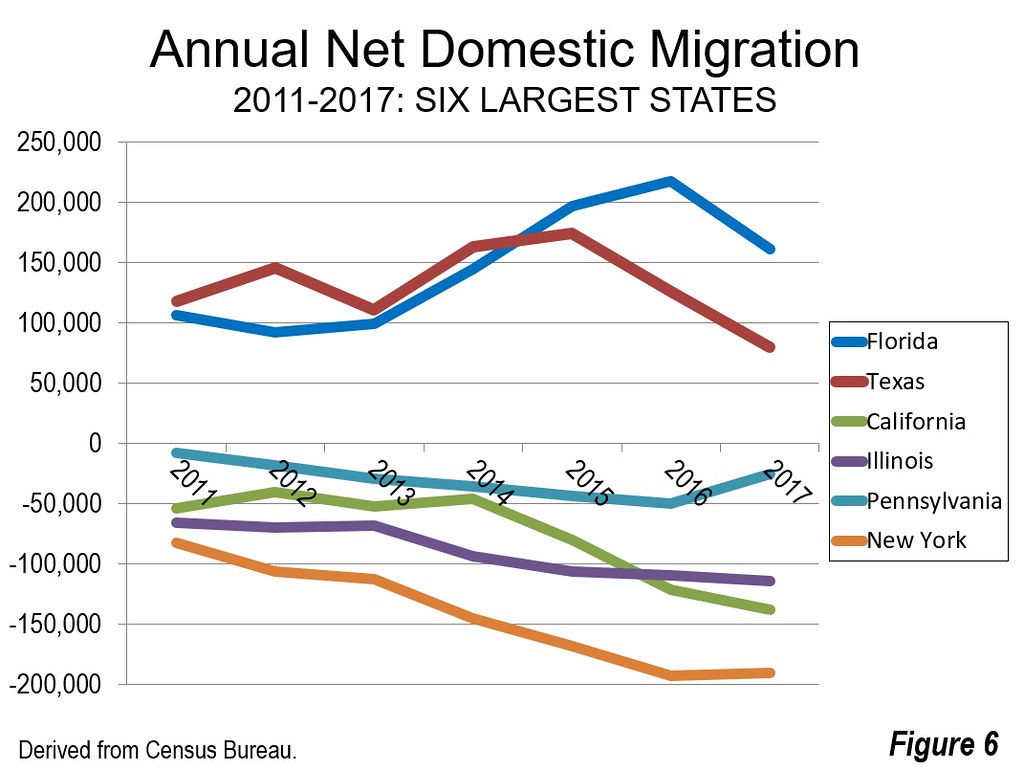

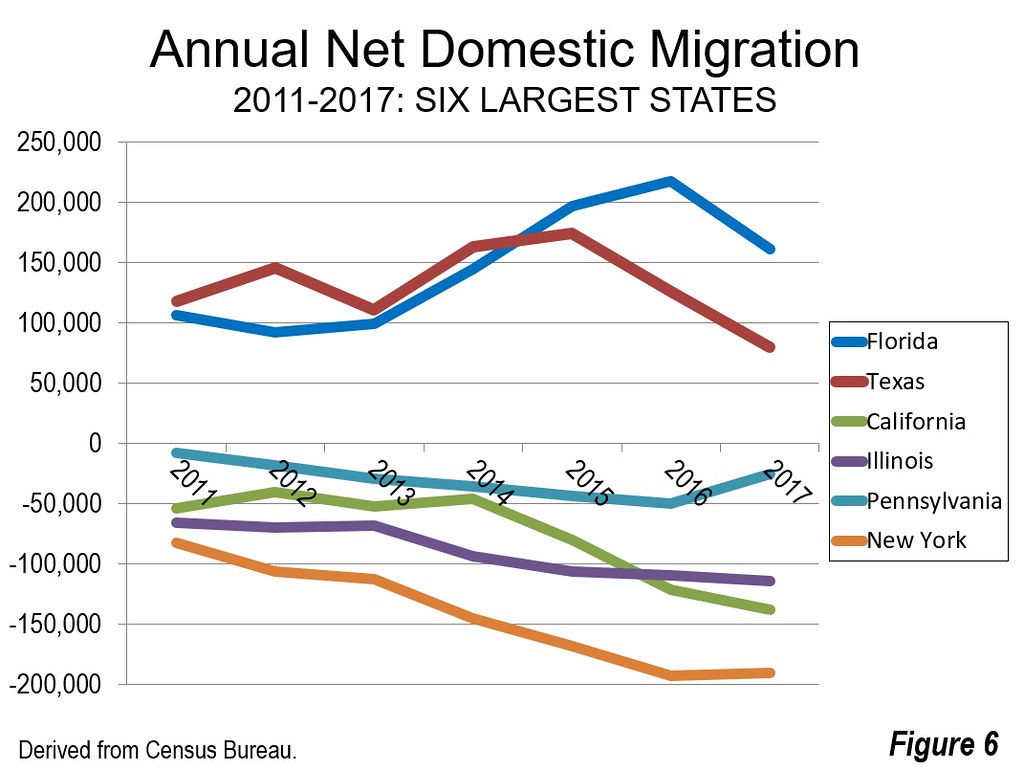

The six largest states experienced significantly different net domestic migration results. Florida has led in net domestic migration, adding 1.025 million residents from other states since 2010. Florida has also led in three of the seven years. Texas led in the first four years of the decade and has added 945,000 net domestic migrants.

Among the other four largest states, the net domestic migration losses have been substantial. The smallest loss has been in Pennsylvania at approximately 215,000. California has lost approximately 545,000 net domestic migrants since 2010, a pattern that has accelerated in recent years. Just three years ago (2014), California had lost fewer than 50,000 net domestic migrants. By 2017, outward net migration had escalated to nearly 140,000. In the first five years of the decade, California had done less poorly in net domestic migration than Illinois. However, in each of the last two years, California has lost more net domestic migrants than Illinois.

Illinois has lost the second largest number of net domestic migrants, at more than 640,000. The losses have escalated from below 75,000 in each of the first three years of the decade to nearly 115,000 in 2017. New York hemorrhaged by far the largest number of net domestic migrants, more than 1,020,000. In each of the last two years, New York has lost approximately 190,000 net domestic migrants, well above its early 80,000 loss in 2011. (Figure 6).

Dominance of the South (and West)

The latest population estimates indicate that the long-term movement to the South and West is continuing. Of course, the biggest exception in the West remains its largest state, California, which has become one of the nation's largest exporters of people since the 1990s. In contrast, Arizona, Washington, Colorado, Oregon, Nevada have attracted large numbers of people. In the South, most states have been gaining domestic migrants, though there are exceptions, especially Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia and Mississippi. But overall the South has been dominant. In each of the last seven years, the South has been the destination for more than 70 percent of US net domestic migration.

The data is summarized in the Table below.

State Population Estimates

2010 - 2017

State & DC April 1, 2010 July 1, 2017 Change % Net Domestic Migration

Alabama 4,785,579 4,874,747 89,168 1.9% 1,153

Alaska 714,015 739,795 25,780 3.6% -37,492

Arizona 6,407,002 7,016,270 609,268 9.5% 278,290

Arkansas 2,921,737 3,004,279 82,542 2.8% 7,222

California 37,327,690 39,536,653 2,208,963 5.9% -556,710

Colorado 5,048,029 5,607,154 559,125 11.1% 276,485

Connecticut 3,580,171 3,588,184 8,013 0.2% -153,276

Delaware 899,712 961,939 62,227 6.9% 25,824

District of Columbia 605,040 693,972 88,932 14.7% 30,787

Florida 18,846,461 20,984,400 2,137,939 11.3% 1,025,261

Georgia 9,712,696 10,429,379 716,683 7.4% 163,536

Hawaii 1,363,817 1,427,538 63,721 4.7% -42,456

Idaho 1,570,912 1,716,943 146,031 9.3% 61,332

Illinois 12,841,196 12,802,023 -39,173 -0.3% -642,821

Indiana 6,490,029 6,666,818 176,789 2.7% -57,864

Iowa 3,050,223 3,145,711 95,488 3.1% -17,695

Kansas 2,858,403 2,913,123 54,720 1.9% -83,158

Kentucky 4,347,948 4,454,189 106,241 2.4% -12,593

Louisiana 4,544,871 4,684,333 139,462 3.1% -47,701

Maine 1,327,568 1,335,907 8,339 0.6% 3,968

Maryland 5,788,099 6,052,177 264,078 4.6% -112,092

Massachusetts 6,564,943 6,859,819 294,876 4.5% -98,948

Michigan 9,876,731 9,962,311 85,580 0.9% -225,302

Minnesota 5,310,711 5,576,606 265,895 5.0% -32,518

Mississippi 2,970,437 2,984,100 13,663 0.5% -59,667

Missouri 5,995,681 6,113,532 117,851 2.0% -57,375

Montana 990,507 1,050,493 59,986 6.1% 37,304

Nebraska 1,829,956 1,920,076 90,120 4.9% -12,289

Nevada 2,702,797 2,998,039 295,242 10.9% 145,131

New Hampshire 1,316,700 1,342,795 26,095 2.0% 2,875

New Jersey 8,803,708 9,005,644 201,936 2.3% -395,160

New Mexico 2,064,607 2,088,070 23,463 1.1% -55,903

New York 19,405,185 19,849,399 444,214 2.3% -1,022,071

North Carolina 9,574,247 10,273,419 699,172 7.3% 327,631

North Dakota 674,518 755,393 80,875 12.0% 39,178

Ohio 11,539,282 11,658,609 119,327 1.0% -192,615

Oklahoma 3,759,529 3,930,864 171,335 4.6% 28,125

Oregon 3,837,073 4,142,776 305,703 8.0% 181,252

Pennsylvania 12,711,063 12,805,537 94,474 0.7% -214,426

Rhode Island 1,053,169 1,059,639 6,470 0.6% -33,615

South Carolina 4,635,834 5,024,369 388,535 8.4% 264,781

South Dakota 816,227 869,666 53,439 6.5% 11,890

Tennessee 6,355,882 6,715,984 360,102 5.7% 178,125

Texas 25,241,648 28,304,596 3,062,948 12.1% 944,018

Utah 2,775,260 3,101,833 326,573 11.8% 50,162

Vermont 625,842 623,657 -2,185 -0.3% -10,179

Virginia 8,025,206 8,470,020 444,814 5.5% -53,500

Washington 6,741,386 7,405,743 664,357 9.9% 249,052

West Virginia 1,854,315 1,815,857 -38,458 -2.1% -28,380

Wisconsin 5,690,403 5,795,483 105,080 1.8% -68,738

Wyoming 564,376 579,315 14,939 2.6% -8,838

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

California Net Migration -556,710

"The latest population estimates indicate that the long-term movement to the South and West is continuing. Of course, the biggest exception in the West remains its largest state, California, which has become one of the nation's largest exporters of people since the 1990s."

http://www.newgeography.com/content/005837-the-migration-millions-2017-state-population-estimates

THE MIGRATION OF MILLIONS: 2017 STATE POPULATION ESTIMATES

by Wendell Cox 12/30/2017

Texas added the most new residents of any state over the past year according to the July 1, 2017 estimates of the United States Census Bureau. Texas grew by 400,000 residents (Figure 1). Florida added 328,000 residents more than one third more than California. Four states grew between 100,000 to 125,000, led by Washington, North Carolina, Georgia and Arizona. Colorado and Tennessee round out the top 10. The ten states adding the most new residents include five from the South census region and five from the West census region.

Population Growth

Over this decade, the three largest states have dominated numeric population growth. Texas has led the nation in each of the seven years, though has experienced declines in growth over the last two due likely to the instability in petroleum markets. Since 2010, Texas has added 3.1 million residents, more than live in 18 states and the District of Columbia. California has added 2.2 million new residents since 2010, edging out Florida. California's growth, however, has dropped significantly, to 240,000 between 2016 and 2017 the smallest number since the late 1990s. California's growth in this decade had peaked in 2014 at more than 350,000, but has since dropped by nearly one quarter. Florida added 2.1 million new residents and has led California in each of the last three years.

The other three largest states did much more poorly. New York has dropped from a gain of over 120,000 in 2011 to only 13,000 in 2017. Illinois has done even more poorly, dropping from the 21,000 gain in 2011 to a loss of 33,000 in 2017. Illinois has experienced a reduction in its growth each year of this decade.

Illinois Drops a Notch: Further, Illinois in 2017 lost its long standing hold on the fifth-largest position to Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania's ascendancy reverses a development in the 1950s, when Illinois passed Pennsylvania to become the third largest state. Less than a decade earlier, Pennsylvania had been passed by California, relinquishing its second ranking, which it had held since the 1810 census. Later, Illinois had been passed in the 1970s by Texas and in the following decade by Florida. (Figure 2).

The South census region has dominated US population growth throughout the decade. Between 2010 and 2017, the South added 9.1 million new residents or 54% of the national growth. This compares to the West, which also grew strongly but added millions fewer (5.5 million new residents). The West accounted for 32% of the national growth. The Midwest and Northeast continue to lag, each taking 7% of the national growth (Figure 3).

Idaho experienced the largest proportional growth rate in 2007, at 2.2%. Idaho was followed closely by its neighbors, Nevada at 2.0% and Utah at 1.9%. The next four positions were taken by large or medium sized states, including Washington at 1.7%, Florida and Arizona at 1.6% and Texas at 1.4%. Colorado and Oregon grew at 1.4%, followed by South Carolina at 1.3% (Figure 4).

Where the Millions are Moving

Despite the fact that interstate migration stands at a lower rate than in recent decades, millions of people continue to cross state lines seeking new residences. From 2010 to 2017, the number was 4.3 million. Domestic migration has been dominated by the South and West census regions, consistent with their dominance of population growth.

The South census region had a net domestic migration gain of 2.7 million residents. The West census region had a gain of 600,000 net domestic migrants, far short of the number in the South. In contrast, a net 1.9 million residents left the Northeast for other census regions, while 1.3 million left the Midwest for elsewhere (Figure 5). Even so, as indicated above, the Northeast and Midwest continue to grow as a result of in migration from other countries and natural growth (births minus deaths).

The six largest states experienced significantly different net domestic migration results. Florida has led in net domestic migration, adding 1.025 million residents from other states since 2010. Florida has also led in three of the seven years. Texas led in the first four years of the decade and has added 945,000 net domestic migrants.

Among the other four largest states, the net domestic migration losses have been substantial. The smallest loss has been in Pennsylvania at approximately 215,000. California has lost approximately 545,000 net domestic migrants since 2010, a pattern that has accelerated in recent years. Just three years ago (2014), California had lost fewer than 50,000 net domestic migrants. By 2017, outward net migration had escalated to nearly 140,000. In the first five years of the decade, California had done less poorly in net domestic migration than Illinois. However, in each of the last two years, California has lost more net domestic migrants than Illinois.

Illinois has lost the second largest number of net domestic migrants, at more than 640,000. The losses have escalated from below 75,000 in each of the first three years of the decade to nearly 115,000 in 2017. New York hemorrhaged by far the largest number of net domestic migrants, more than 1,020,000. In each of the last two years, New York has lost approximately 190,000 net domestic migrants, well above its early 80,000 loss in 2011. (Figure 6).

Dominance of the South (and West)

The latest population estimates indicate that the long-term movement to the South and West is continuing. Of course, the biggest exception in the West remains its largest state, California, which has become one of the nation's largest exporters of people since the 1990s. In contrast, Arizona, Washington, Colorado, Oregon, Nevada have attracted large numbers of people. In the South, most states have been gaining domestic migrants, though there are exceptions, especially Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia and Mississippi. But overall the South has been dominant. In each of the last seven years, the South has been the destination for more than 70 percent of US net domestic migration.

The data is summarized in the Table below.

State Population Estimates

2010 - 2017

State & DC April 1, 2010 July 1, 2017 Change % Net Domestic Migration

Alabama 4,785,579 4,874,747 89,168 1.9% 1,153

Alaska 714,015 739,795 25,780 3.6% -37,492

Arizona 6,407,002 7,016,270 609,268 9.5% 278,290

Arkansas 2,921,737 3,004,279 82,542 2.8% 7,222

California 37,327,690 39,536,653 2,208,963 5.9% -556,710

Colorado 5,048,029 5,607,154 559,125 11.1% 276,485

Connecticut 3,580,171 3,588,184 8,013 0.2% -153,276

Delaware 899,712 961,939 62,227 6.9% 25,824

District of Columbia 605,040 693,972 88,932 14.7% 30,787

Florida 18,846,461 20,984,400 2,137,939 11.3% 1,025,261

Georgia 9,712,696 10,429,379 716,683 7.4% 163,536

Hawaii 1,363,817 1,427,538 63,721 4.7% -42,456

Idaho 1,570,912 1,716,943 146,031 9.3% 61,332

Illinois 12,841,196 12,802,023 -39,173 -0.3% -642,821

Indiana 6,490,029 6,666,818 176,789 2.7% -57,864

Iowa 3,050,223 3,145,711 95,488 3.1% -17,695

Kansas 2,858,403 2,913,123 54,720 1.9% -83,158

Kentucky 4,347,948 4,454,189 106,241 2.4% -12,593

Louisiana 4,544,871 4,684,333 139,462 3.1% -47,701

Maine 1,327,568 1,335,907 8,339 0.6% 3,968

Maryland 5,788,099 6,052,177 264,078 4.6% -112,092

Massachusetts 6,564,943 6,859,819 294,876 4.5% -98,948

Michigan 9,876,731 9,962,311 85,580 0.9% -225,302

Minnesota 5,310,711 5,576,606 265,895 5.0% -32,518

Mississippi 2,970,437 2,984,100 13,663 0.5% -59,667

Missouri 5,995,681 6,113,532 117,851 2.0% -57,375

Montana 990,507 1,050,493 59,986 6.1% 37,304

Nebraska 1,829,956 1,920,076 90,120 4.9% -12,289

Nevada 2,702,797 2,998,039 295,242 10.9% 145,131

New Hampshire 1,316,700 1,342,795 26,095 2.0% 2,875

New Jersey 8,803,708 9,005,644 201,936 2.3% -395,160

New Mexico 2,064,607 2,088,070 23,463 1.1% -55,903

New York 19,405,185 19,849,399 444,214 2.3% -1,022,071

North Carolina 9,574,247 10,273,419 699,172 7.3% 327,631

North Dakota 674,518 755,393 80,875 12.0% 39,178

Ohio 11,539,282 11,658,609 119,327 1.0% -192,615

Oklahoma 3,759,529 3,930,864 171,335 4.6% 28,125

Oregon 3,837,073 4,142,776 305,703 8.0% 181,252

Pennsylvania 12,711,063 12,805,537 94,474 0.7% -214,426

Rhode Island 1,053,169 1,059,639 6,470 0.6% -33,615

South Carolina 4,635,834 5,024,369 388,535 8.4% 264,781

South Dakota 816,227 869,666 53,439 6.5% 11,890

Tennessee 6,355,882 6,715,984 360,102 5.7% 178,125

Texas 25,241,648 28,304,596 3,062,948 12.1% 944,018

Utah 2,775,260 3,101,833 326,573 11.8% 50,162

Vermont 625,842 623,657 -2,185 -0.3% -10,179

Virginia 8,025,206 8,470,020 444,814 5.5% -53,500

Washington 6,741,386 7,405,743 664,357 9.9% 249,052

West Virginia 1,854,315 1,815,857 -38,458 -2.1% -28,380

Wisconsin 5,690,403 5,795,483 105,080 1.8% -68,738

Wyoming 564,376 579,315 14,939 2.6% -8,838

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

NYC Woman Shows Her Loft Apartment That She Has Lived in for 29 Years

Urban YIMBYs can learn from the experience of New Yorkers. There is no FREE LUNCH. Gentrifiers push out minorities, artists and the middle class. Only the rich and the resilient remain.

Friday, December 29, 2017

California officials say housing next to freeways is a health risk — but they fund it anyway

California officials say housing next to freeways is a health risk — but they fund it anyway

By TONY BARBOZA and DAVID ZAHNISER

DEC 17, 2017 | 5:00 AM

Traffic flows on the I-5 near the Sheldon Street exit where an empty lot is a possible site for a homeless veterans housing complex in Sun Valley on December 12, 2017. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Traffic flows on the I-5 near the Sheldon Street exit where an empty lot is a possible site for a homeless veterans housing complex in Sun Valley on December 12, 2017. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) It’s the type of project Los Angeles desperately needs in a housing crisis: low-cost apartments for seniors, all of them veterans, many of them homeless.

There’s just one downside. Wedged next to an offramp, the four-story building will stand 200 feet from the 5 Freeway.

State officials have for years warned against building homes within 500 feet of freeways, where people suffer higher rates of asthma, heart disease, cancer and other health problems linked to car and truck pollution. Yet they’re helping build the 96-unit complex, providing $11.1 million in climate change funds from California’s cap-and-trade program.

The Sun Valley Senior Veterans Apartments is one of at least 10 affordable housing projects within 500 feet of a freeway awarded a total of $65 million in cap-and-trade money since 2015, a Times review of records found. Those developments will place hundreds of apartments for homeless people, veterans and families near freeways in Los Angeles, the Bay Area and the Central Valley, some less than 100 feet from traffic.

California’s support for those projects shows how policies created to cut greenhouse gases and ease the housing crunch are also putting some of the state’s neediest residents at risk from traffic pollution. It's one way public dollars are helping finance a surge in residential development near freeways, where Los Angeles and other California cities have permitted thousands of new homes in recent years.

How close do you live to the freeway? »

State officials acknowledge that some cap-and-trade money, collected from companies that buy permits to emit greenhouse gases, will put residents near elevated levels of pollution. But they say dense housing near bus and rail lines is crucial to meeting California’s climate goals, by getting cars off the road.

Even in places with poor air quality, they argue, residents’ health will improve from walking and biking more. And they say the dangers from living near freeways can be reduced with anti-pollution design features recommended this year by state air regulators, including sound walls, vegetation barriers and high-efficiency air filters that remove some of the harmful particles from vehicle exhaust.

“When those strategies are employed, the environmental and public health benefits of these projects far outweigh the negatives,” said Ken Alex, a senior advisor to Gov. Jerry Brown who chairs the Strategic Growth Council, the agency that distributes cap-and-trade funds to affordable housing developers.

California’s decision to subsidize low-income housing near freeways alarms some health scientists, who point to years of studies that link roadway pollution with a growing list of illnesses — and billions in healthcare costs. They say air filters and other mitigation measures are not enough to protect residents, especially children, whose lungs could be damaged for life, and seniors, who could die early from heart attacks.

“I see the economic incentives for doing this,” said Beate Ritz, an environmental epidemiologist at UCLA who has studied the health effects of traffic pollution for more than two decades. “But it’s kind of stupid, because we all know we will pay for it with long-term health effects. Somebody has to pay for the costs of diabetes, of cognitive decline or strokes. This is just creating a huge amount of costs for society in the long run.”

Construction is expected to start within weeks on the Sun Valley project, capping a decade of debate that pitted the need for more housing against the health of people who would live there. Proponents say those apartments will be far superior to life on the street, with higher-rated air filters and a buffer — dozens of trees, a sound wall and a parking lot — separating residents from pollution.

Despite those measures, some locals argue the freeway is simply too close.

“These vets are going to be sucking in these diesel fumes. It’s going to shorten their lives,” said Mike O’Gara, who lives eight blocks away and is a veteran of the U.S. Naval Air Forces. “What a hell of a great reward for serving their country.”

Unpleasant choices

The Sun Valley project offers a window into the unpleasant choices faced by politicians, real estate developers and nonprofit groups as they struggle to counter rising rents and a surge in homelessness, which grew 23% this year across Los Angeles County, to nearly 58,000 people.

Los Angeles, a city crisscrossed by freeways, is embarking on a $1.2-billion plan aimed at financing 10,000 homes for homeless people. Land next to those corridors — often cheaper and less likely to spur outcry from neighborhood groups — will be tempting to build on.

If policymakers put low-cost housing next to freeways, they will place some of their poorest constituents in locations where pollution can be five to 10 times higher, saddling them with the health consequences. But if they prohibit new construction in those areas, they could make things tougher for people trying to get off, or stay off, the streets.

Of the roughly 2,000 affordable housing units approved in Los Angeles in 2016, 1 in 4 was within 1,000 feet of a freeway, according to figures from the Department of City Planning. Officials are weighing whether to build homeless housing on at least nine city-owned properties within 500 feet of freeways — including one that’s less than 200 feet from the sprawling 110-105 freeway interchange.

Housing advocates point to studies that link homelessness to early deaths from drug use, respiratory disorders and other health problems. Homeless individuals are also less likely to obtain access to healthcare, mental health services and substance abuse counseling than those who have shelter, said Mike Alvidrez, chief executive of Skid Row Housing Trust, which has built 1,800 units of housing since 1989 — including one building next to the 10 Freeway.

“We know that people die sooner if they don’t get off the street and into housing. We just know that,” he said. “So if you have a solution that going to prolong someone’s life — irrespective of whether it’s the worst place you could put it, next to a freeway or next to two freeways — if you don’t have another option, that’s what you do.”

Across the region, homeless people are already living near freeways — in tents tucked along sound walls, in campsites obscured by shrubbery. Jason McKenney, 34, said he has spent some nights in North Hollywood Park, which runs along the 170 Freeway.

Sitting under a tree nursing an injured leg, the onetime construction worker said he would have no qualms about moving into a building next to a freeway, if it had cheap rents and counseling for substance abuse.

“I would jump at that chance,” he said.

Apartments near transit

With climate change now a top priority, California has embraced policies to cut carbon emissions by packing dense housing near jobs and transit. State leaders have set aside nearly $700 million from the cap-and-trade program to finance transit-oriented developments and infrastructure.

The planned Sun Valley development is on a noisy stretch of Laurel Canyon Boulevard with high-speed traffic and few walkable businesses. But because it’s near a bus stop, the project was eligible for cap-and-trade funds.

To boost transit use near the senior housing complex, a portion of those funds will go toward free bus and rail passes for the tenants, as well as new crosswalks, sidewalks and wheelchair ramps.

Like many projects that have received cap-and-trade money, the project is in a location that already endures a heavy pollution burden, which helped it qualify for state funds. The application for cap-and-trade money acknowledged the neighborhood has high rates of asthma.

Some in the neighborhood, such as 75-year-old Joan Winget, see the freeway as a serious health threat. Diagnosed with emphysema in 2012, Winget has lived more than 20 years in a mobile home park right next to the senior housing site.

The retired property manager smoked cigarettes until 1979, and her health issues are linked at least in part to that habit. But she worries her medical problems have been exacerbated by pollution from the nearby 5-170 freeway interchange, whose swooping ramps can be seen from the property’s driveway.

Each day, about 200,000 vehicles on the 5 pass her home. To protect herself, Winget keeps her doors and windows closed 24/7 and the air conditioning running around the clock. She misses the days when she let a breeze blow through her home late at night.

“I hate it,” she said. “I love fresh air. I like getting outside. I don’t like being stuck in the house all the time. I might not be getting the greatest air in here, but it’s worse outside.”

Regulators say decades of tough clean-air rules have slashed tailpipe emissions, reducing risks to people near freeways. But some scientists warn those health improvements will be undercut by the state’s push to concentrate high-density housing near transit hubs, which often sit near major roadways.

A 2016 study projected state climate policies would increase the number of preventable deaths from heart disease in Southern California by placing more people near traffic pollution. Establishing buffers between homes and heavy traffic, in contrast, would decrease heart disease deaths, especially among the elderly, according to the study by researchers from USC, the California Department of Public Health and several other institutions.

The state Air Resources Board — which since 2005 has recommended municipalities “avoid siting” homes within 500 feet of freeways — oversees the spending of billions of dollars in cap-and-trade funds by a dozen state agencies. But the board does not select the affordable housing projects that get the money. Those decisions rest with the Strategic Growth Council, a committee appointed by the governor and state lawmakers.

Records show the Strategic Growth Council voted unanimously to award funds for apartments next to the 110 Freeway in Los Angeles, housing along Highway 99 in Turlock and a 135-unit building in San Jose that’s just 25 feet from Highway 87, a location a state analysis ranks in the 95th percentile for diesel emissions.

At least one member of the panel, Manuel Pastor, said he was unaware he had voted for housing so close to freeways.

Pastor, who directs USC’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and has written on the health implications of building near roadway pollution, said the issue never came up when the projects were being considered.

“Your pointing out the exact location of these projects is the first time it has come to my attention,” said Pastor, an appointee of State Senate leader Kevin de León. “I have not until now asked for a map of where these things are.”

‘Poor planning and bad zoning’

The push to build homes on the Sun Valley site began more than a decade ago, just as Los Angeles city officials were starting to reckon with the health risks posed by freeway-adjacent development.

Initially, the zoning for the site allowed for just three homes. The City Council hiked that number to 26 in 2008, at the request of the property’s owners. Three years later, the same developers asked the city to increase the number again, taking it to 96.

Each step of the way, there were warnings about freeway pollution — first from planning commissioners, then neighbors, and finally the South Coast Air Quality Management District. Early on, one mayoral appointee called it an example of “poor planning and bad zoning.”

But the developers had a champion in U.S. Rep. Tony Cardenas, who represented the area.

Cardenas and two of his allies, then-State Sen. Alex Padilla and then-Assemblyman Raul Bocanegra, urged city leaders in 2013 to allow a 96-unit elder care facility to go up on the site. All three have received a steady stream of political contributions from developers, architects and others who worked on the Sun Valley development — at least $70,350 over the last 15 years, a Times review of donations found.

The elder care project was approved, and in 2015, the owners sold it for $3.5 million, more than three times the amount paid in 2006, when only three homes could be built on the site.

Neither Cardenas nor Bocanegra would comment for this story. Padilla, now California’s secretary of state, said he supported the project because it offered “affordable living options for senior citizens.”

Businessman David Spiegel, one of the project’s developers at the time, said he followed the city’s rules. “There are hundreds of thousands of units that have been and are currently being built on the freeway,” he said, “so any impacts must be acceptable to city, state and federal agencies.”

Sealing windows shut

The property was purchased by the East L.A. Community Corp., a nonprofit housing developer with experience putting low-income housing next to freeways. ELACC, as the group is known, had already built 33 apartments for homeless veterans along the 5 Freeway in Boyle Heights. At that location, windows facing the freeway are sealed shut and the air conditioning system has higher-rated filters.

Isela Gracian, the nonprofit group’s president, said many of L.A.’s low-income neighborhoods were carved up by freeways decades ago. That, she said, makes it difficult to find properties far from car and truck pollution.

“Not every piece of land is available to us,” she said. “Whoever currently owns the land has to be willing and open to selling the property. It’s not like we can walk the streets and say, ‘This is a better location — let’s swap the project and move it over here.’ ”

Still, one agency in Los Angeles County has managed to avoid putting its money into projects along freeways.

The county’s Community Development Commission, which provides tens of millions of dollars in low-interest loans to affordable housing developers each year, decided in 2008 that it would not allow its money to finance projects within 500 feet of a freeway.

Kathy Thomas, who heads the agency, said that decision was made in response to warnings about the health hazards of traffic pollution from the Air Resources Board and other regulators. Yet even with that limitation, the commission finances hundreds of units of housing each year — and receives more requests for money than it has to lend, she said.

“We have not had any difficulty finding projects,” Thomas said in an email. “Our freeway buffer requirement is well-known among developers and we really don’t get any pushback.”

Thomas said it would be “negligent” for her agency to knowingly put low-cost housing next to freeways and undermine the county’s work in reducing “the cost burden of frequent users on the healthcare system.”

Some officials want similar conditions on the spending of cap-and-trade funds.

Dean Florez, a former state senator who sits on the Air Resources Board, said California should stop using cap-and-trade money for housing near freeways. Those projects, he said, “will endanger people’s lungs for decades.”

The Strategic Growth Council is moving ahead without such restrictions as it accepts applications for another $255 million in affordable housing funds.

Agency officials will score projects by proximity to transit, greenhouse gas reductions, walkability and other criteria. One thing they won’t measure is how close the projects are to freeway pollution.

Thursday, December 28, 2017

New Laws affecting real estate in Califronia as of January 1, 2018

|

| 2017 saw approval of the most Radical Housing Laws yet and may force urban development in Marin County and other suburbs. |

Lots to unpack here:

Housing

Streamlined

Affordable Housing

Production

Creates streamlined

“Build-by-right”

Creates a streamlined, ministerial approval process for infill

projects with two or more residential units in localities that have

failed to meet their regional housing needs assessment numbers.

This law creates a streamlined "by-right" approval process for infill

projects with two or more residential units or Accessory Dwelling Units in

localities that have failed to produce sufficient housing to meet their

Regional Housing Needs Assessment goals, provided that the project: 1)

approval process for

infill projects with two

or more residential

units or accessory

dwelling units for

certain localities

is not located in a hazard zone (e.g., flood, fire, earthquake, etc.); 2)

dedicates 10% of the units to households making at or below 80% of the

area median income; and 3) pays prevailing wage to projects over 10

units.

The streamlined approval process requires some level of affordable

housing to be included in the housing development. To receive the

streamlined process for housing developments, the developer must

demonstrate that the development meets a number of requirements.

Localities must provide written documentation to the developer if there is

a failure to meet the specifications for streamlined approval, within

specified periods of time. If the locality does not meet those deadlines,

the development shall be deemed to satisfy the requirements for

streamlined approval.

“Infill” is the use of land within a built-up area for further construction.

Background

Each community’s general plan must include a housing element, which

outlines a long-term plan for meeting the community’s existing and

projected housing needs. The housing element demonstrates how the

community plans to accommodate its “fair share” of its region’s housing

needs. To do so, each community establishes an inventory of sites

designated for new housing that is sufficient to accommodate its fair

share. Communities also identify regulatory barriers to housing

development and propose strategies to address those barriers. State law

requires cities and counties to update their housing elements every eight

years. In addition, before building new housing, housing developers

must obtain one or more permits from local planning departments and

must also obtain approval from local planning commissions, city

councils, or county boards of supervisors. Some housing projects can be

permitted by city or county planning staff ministerially or without further

approval from elected officials. Projects reviewed ministerially require

only an administrative review designed to ensure they are consistent

with existing general plan and zoning rules, as well as meet standards

for building quality, health, and safety. Most large housing projects are

not allowed ministerial review. Instead, these projects are vetted through

both public hearings and administrative review. Most housing projects

that require discretionary review and approval are subject to California

Environmental Quality Act review, while projects permitted ministerially

generally are not

..

SB 35 codified as §§ 65400 and 65582.1 of the Government

Code. Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Enforcement of

California Housing

Laws

The law enhances the authority of the Department of Housing and

Community Development (HCD) to determine if a locality is in

compliance with its general plans for housing development.

The existing Planning and Zoning Law requires a city or county to adopt

a comprehensive, long-term general plan for the physical development

of the city or county and of any land outside its boundaries that bears

relation to its planning. That law also requires the general plan to contain

specified mandatory elements, including a housing element for the

preservation, improvement, and development of housing which must be

submitted to the Department of Housing and Community Development

(the HCD) prior to the adoption of the element or amendment to the

element. The HCD then reviews the draft to determine whether the draft

substantially complies with the housing element.

This law further requires the HCD to also review any action or failure to

act by the city, county, or city and county that it determines is

inconsistent with an adopted housing element or a specified provision

and to issue written findings as to whether the action or failure to act

substantially complies with the housing element. If the HCD finds that

the action or failure to act by the city, county, or city and county does not

substantially comply with the housing element, and if it has issued

findings as described above that an amendment to the housing element

substantially complies with the housing element, this law authorizes the

HCD, after allowing no more than 30 days for a local agency response,

to revoke its findings until it determines that the city, county, or city and

county has come into compliance with the housing element. This law

also requires the HCD to notify the city, county, or city and county and

authorizes the HCD to notify the Office of the Attorney General that the

city, county, or city and county is in violation of state law if the

HCD finds noncompliance or a violation.

Assembly Bill 72 codified as Government Code § 65585.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Permits developers to

voluntarily use an

alternate zoning and

environmental

approval process in a

housing sustainability

district

Allows a city or county to create a housing sustainability district to

complete upfront zoning and environmental review in order to

receive incentive payments for development projects that are

consistent with the district's ordinance.

This law provides local governments the option of creating "Housing

Sustainability Districts," which operate as overlay districts to streamline

the residential development process in areas with existing infrastructure

and transit. These districts would be zoned at higher densities, near

public transit, and an EIR on the district would be completed at the front

end. Additionally, 20% of the housing in the district must be zoned at

affordable levels. Any development affordable to persons and families

whose income exceeds moderate-income shall contain no less than 10%

units for lower-income households. Once zoning is complete, the

housing sites within the district would be subject to ministerial approval

and subject to prevailing wage. In exchange for creating Districts,

localities receive incentive payments to encourage their establishment of

these districts, at two stages: a) First, local governments receive an

incentive payment when they create Districts. This payment would be

issued by the HCD upon preliminary approval of the district ordinance

and issuance of the EIR. b) Once a city permits housing units within a

district and demonstrates it has received a certificate of compliance from

HCD, it would receive a second incentive payment. This payment would

be issued by HCD. This law seeks to expedite and streamline local

housing development approval processes by exempting project-level

environmental review. Additionally, this law requires the locality to issue

a written decision within 120 days of receipt of the application.

Assembly Bill 73 codified as Government Code §§ 65582.1 and 66200

et. seq., and Public Resources Code § 21155.10 et. seq.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Ensures that local

agencies cannot

disapprove housing

projects without a

preponderance of

evidence proving that

the project adversely

impacts public health

or safety.

Changes the standard for a locality to disapprove development

from “substantial evidence” which is a relatively low threshold to a

“preponderance of the evidence.”

Purpose: This law seeks to address the severity of California’s housing

crisis by taking a critical look at cities’ approval processes for

development. State courts are often too deferential to localities in

accepting any justification declaring a development not feasible.

Although there is an evident lack of funding, space, and construction,

there are solutions the state can implement to ensure development is

taking place in conjunction with a city’s general plan and zoning

ordinance.

Under current law and the current Housing Accountability Act (HAA), for

affordable projects or emergency shelters, a local government may not

disapprove the development or condition approval in a manner that

renders the project not feasible unless it makes written findings, based

upon substantial evidence in the record, as to at least one of five

elements. For other types of housing projects, the local government may

not deny the proposed housing development or condition its approval

upon lower density unless it makes written findings, supported by

substantial evidence on the record, that it is necessary to safeguard

human health and safety. Substantial evidence, which is a relatively low

threshold, is "such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept

as adequate to support a conclusion." (Richardson v. Perales (1971) 402

United States 389.)

This new law requires a local government to make these findings by a

"preponderance of the evidence" rather than "substantial" evidence. The

preponderance of the evidence standard is higher than the substantial

evidence standard, and the evidence provided has to convince the

decision maker that it is "more likely than not." It is the standard

employed in most civil legal cases and is sometimes expressed in

statistical terms as 50% plus one. The purpose of this provision is to

impose a higher standard on local governments that wish to deny or

impose certain conditions on housing projects that qualify for the

protections of the HAA.

Fines and punitive damages: Under existing law, a court may impose

fines upon a local agency for acting in bad faith. The new law requires a

court to impose a minimum fine of $10,000 per housing unit in the

housing development project if the court finds a violation of the HAA.

Change in zoning or land use designation not valid for disapproval: The

new law provides that a change in a zoning ordinance or general plan

land use designation subsequent to the date the application was

deemed complete does not constitute a valid basis to disapprove or

condition approval of the housing development project or emergency

shelter.

Assembly Bill 678 and Senate Bill 167 codified as Government Code §

65589.5.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Seeks to identify

solutions to the state’s

housing crisis using

the housing element

planning process

Requires a more detailed and broader housing element planning

process with an eye toward removing obstacles that may hinder a

locality from meeting its general housing plan.

Background: Every local government is required to prepare a housing

element as part of its general plan. The housing element process starts

when The Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD)

determines the number of new housing units a region is projected to

need at all income levels (very low-, low-, moderate-, and above moderate

income) over the course of the next housing element planning

period to accommodate population growth and overcome existing

deficiencies in the housing supply. This number is known as the RHNA.

The Council of Governments (COG) for the region, or HCD for areas

with no COG, then assigns a share of the RHNA number to every city

and county in the region based on a variety of factors.

In preparing its housing element, a local government must show how it

plans to accommodate its share of the RHNA. The housing element

must include an assessment of housing needs and an inventory of

resources and constraints relevant to the meeting of these needs.

Included in this analysis is an assessment of both governmental and

nongovernmental constraints upon the maintenance, improvement, or

development of housing for all income levels, including the availability of

financing, the price of land, and the cost of construction.

Governmental and nongovernmental constraints: Existing law

requires the housing element to include an analysis of potential and

actual governmental and nongovernmental constraints upon the

maintenance, improvement, or development of housing for all income

levels. The analysis of governmental constraints must include land use

controls, building codes and their enforcement, site improvements, fees

and other exactions required of developers, and local processing and

permit procedures.

This new law would require the analysis of governmental constraints to

also include any locally adopted ordinances that directly impact the cost

and supply of residential development. Nothing under existing law would

prevent a local government from providing this information, but this law

requires all local governments to undertake this expanded analysis of

governmental constraints.

Existing law requires the analysis of nongovernmental constraints to

include the availability of financing, the price of land, and the cost of

construction.

This new law also require the analysis of nongovernmental constraints to

include information about any requests to develop housing at lower

densities below those specified in the housing element's analysis of

density levels zoned to accommodate the local government's share of

the RHNA, the length of time between receiving approval for a housing

development and submittal of an application for building permits for that

housing development that hinder the construction of a local

government's share of the RHNA, and any local efforts to remove

nongovernmental constraints that create a gap between the local

government's planning for the development of housing for all income

levels and the construction of that housing..

Existing law also requires a local government's housing element to

address and, where appropriate and legally possible, remove

governmental constraints to the maintenance, improvement, and

development of housing. This law would expand this analysis by

requiring the housing element to also address and remove

nongovernmental constraints

Annual general plan report: This law requires charter cities to comply

with requirements for the submittal of the annual general plan report, and

adds that the report shall include the following: 1) the number of housing

development applications received in the prior year; 2) the number of

units included in all development applications in the prior year; 3) the

number of units approved and disapproved in the prior year; and 4) a

listing of sites rezoned to accommodate that portion of the local

government's share of the regional housing need for each income level

that could not be accommodated on sites identified in the housing

element's site inventory. This must also include any additional sites that

may have been required to be identified under No Net Loss Zoning law.

Assembly Bill 879 codified as Government Code §§ 6500, 65583 and

65700, and Health and Safety Code § 50456.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Authorizes local

governments to

establish Workforce

Housing Opportunity

Zones by preparing an

Environmental Impact

Report pursuant to the

California

Environmental Quality

Act.

This law authorizes a local government to establish a Workforce

Housing Opportunity Zone (WHOZ) which includes and upfront

environmental review (EIR) pursuant to the California

Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The importance of this is that

CEQA has reportedly been used as a barrier to housing projects

even after those housing projects have been subject to lengthy

public discussion and scrutiny, and have been approved by local

governments.

This law permits a locality to establish a WHOZ by preparing an EIR

pursuant to CEQA and adopting a specific plan. For the next five years,

absent unforeseen environmental conditions, a locality may not deny a

development that meets the mitigation requirements under this bill, and

is located within the WHOZ. In effect, this law eliminates project-specific

environmental review, which could allow for housing developments

within the WHOZ to proceed in an expedited manner.

Within a WHOZ, at least 30% of the total units constructed or

substantially rehabilitated in the zone must be sold or rented to

moderate- or middle-income persons or families; at least 15% must be

sold or rented to lower-income persons or families; and at least 5% must

be restricted to very-low income persons or families. No more than 50%

of the total units constructed or substantially rehabilitated may be sold or

rented to persons or families of above moderate- income.

This law makes the local government eligible to apply for a grant or no interest

loan from the Department of Housing and Community

Development and possibly other funding.

This law is related legislation to Senate Bill 35 which creates a

streamlined, ministerial approval process for infill developments in

localities that have failed to meet their regional housing needs

assessment numbers.

Senate Bill 540 codified as Government Code § 65620 et. seq.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Recording

Tax

Recording Tax

Revenues Allocated to

Housing Fund.

Recording fees to be

increased to between

$75 and $225 per

transaction. Sales

transactions and

transfers to owner-occupiers

are

exempted.

A fee of $75 is imposed at the time of recording of every real estate

instrument, paper or notice which is required or permitted to be

recorded. The fee shall not exceed $225 per transaction.

However, the fee does not burden purchase transactions or sales in

general based on the two following exemptions. First, the fee is not

imposed for any document recorded in connection with a transfer

of real property that is a residential dwelling to an owner-occupant.

Second, the fee is not imposed whenever a documentary transfer

tax (DTT) must be paid which is whenever real property is sold for

valuable consideration.

The most common circumstances when the fee would be imposed

are refinances or reconveyances.

The funds generated by this fee are dedicated as follows: 20% of all

funds are specifically dedicated to affordable owner-occupied

workforce housing. Overall, the allocation is 70% of revenues will

go to local governments for housing and 30% is distributed by the

Department of Housing and Community Development and the

California Housing Finance Agency

A fee of seventy-five dollars ($75) shall be paid at the time of recording

of every real estate instrument, paper, or notice required or permitted by

law to be recorded per each single transaction per parcel of real

property, not to exceed two hundred twenty-five dollars ($225). “Real

estate instrument, paper, or notice” means a document relating to real

property, including, but not limited to, the following: deed, grant deed,

trustee’s deed, deed of trust, reconveyance, quit claim deed, fictitious

deed of trust, assignment of deed of trust, request for notice of default,

abstract of judgment, subordination agreement, declaration of

homestead, abandonment of homestead, notice of default, release or

discharge, easement, notice of trustee sale, notice of completion, UCC

financing statement, mechanic’s lien, maps, and covenants, conditions,

and restrictions.

Exemptions: The fee will not be imposed on sales transactions or on

any transfer to an owner occupant. Specifically, the law exempts

transfers in which the documentary transfer tax must be paid or in

connection with a transfer of real property that is a residential dwelling to

an owner-occupier.

Funds Allocated to Affordable Housing

Generally, this law dedicates 20% of the funds to affordable workforce

housing and 70% to local governments for housing.

The precise allocation of funds is as follows:

Jan 1, 2018 to Dec 31, 2018 (first year):

A) 50% of money to update local government housing elements

B) 50% to HCD to assist with homelessness programs

Beginning Jan 1, 2019 (in perpetuity):

A) 20% of ALL money collected goes to affordable owner-occupied

workforce housing

B) 70% of money collected goes to local governments/ distributed based

on HUDs block grant formula

90% of money will be allocated similar to HUD Block Grant distribution

formula

10% of money will be allocated equally to non-entitlement areas

C) 30% of money in the fund is distributed by HCD and CalFHA:

- 5% appropriated by the Legislature to the Multifamily Housing Program

- 10% appropriated by the Legislature to affordable homeownership and

rental housing opportunities for ag and farm workers

- 15% to CalFHA to create mixed income multifamily residential housing

for lower to moderate income households (up to 80% AMI)

- Remainder allocated to local governments

Senate Bill 2 codified as Government Code § 27388.1 and Health and

Safety Code § 50470 et. seq.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Package of 15 housing

bills

The housing bills discussed above are part of a package of 15 housing

bills that were signed into law. These laws are intended to streamline

new housing developments, enforce the Housing Accountability Act, and

provide a permanent source of funding for affordable housing projects.

This package of laws also included the following:

SB 3 (Beall) authorizes $4 billion in general obligation bonds for

affordable housing programs and a veteran's home ownership program.

SB 3 must be approved by voters next November.

"Senate Bill 3 gives California the opportunity to build $15 billion in

much-needed affordable housing for working families, seniors, vets, and

the homeless," said Senator Jim Beall (D-San Jose). "Together, SB 3

and the housing bills signed today represent a historic step to expand a

limited housing supply and counterbalance the skyrocketing market that

threatens our future and economy. More Californians will be able to live

in the community where they work and spend less time on congested

roads.''

SB 166 (Skinner) ensures that cities maintain an ongoing supply of

housing construction sites for residents of various income levels.

AB 571 (E. Garcia) makes it easier to develop farmworker housing by

easing qualifications for the Farmworker Housing Tax Credit.

"I truly want to commend Governor Brown, Speaker Rendon and

Chairman Chiu for leading the charge to address our state's severe

housing crisis," said Assembly member Eduardo Garcia (D-Coachella).

"I was proud to support this comprehensive package of bills, anchored

around SB 2 and SB 3, which established a funding mechanism for

these critical measures, and play my part advocating on behalf of rural

Californian communities, like those in my district that have been

historically underserved. AB 571 eases eligibility requirements for a state

tax credit for developers to build migrant housing. Farmworker labor

fuels our economies, yet these areas lack the necessary investments to

spur growth and prosperity. These modifications to the Farmworker

Housing Assistance Tax Credit Program, along with other programs

established within this historic bill package, will help ensure the essential

right to safe, affordable housing for more of our hard working families

and veterans across California."

AB 1397 (Low) makes changes to the definition of land suitable for

residential development to increase the number of sites where new

multifamily housing can be built.

"No one should be denied a place to call home," said Assembly member

Evan Low (D-Campbell). "This housing package will help make our

Golden State shine bright again."

AB 1505 (Bloom/Bradford/Chiu/Gloria) authorizes cities and counties to

adopt an inclusionary ordinance for residential rental units in order to

create affordable housing.

"The skyrocketing cost of housing is forcing millions of Californians to

make stressful financial decisions every month just to keep the eviction

notice off their front door," said Assembly member Richard H. Bloom (DSanta

Monica). "Our housing problem is real and devastating to families,

seniors, and young adults in communities throughout this state. Today's

signing of AB 1505 ensures that real affordable housing is built so our

teachers, grocery clerks, car mechanics, and retired seniors - those who

we interact with every day and who make up the fabric of our

communities - can also afford to live in our communities."

"People shouldn't have to the leave the state in order to find affordable

housing or achieve the American dream of home ownership," said

Senator Steven Bradford (D-Gardena.)

"Skyrocketing housing costs have squeezed California's working and

middle class for too long," said Assembly member Todd Gloria (D-San

Diego). "I am proud to join the Governor and my fellow legislators to

pass a historic package of bills that makes specific and tangible progress

to give some relief to those struggling to pay their rents and mortgages.

We have more work to do on housing affordability and I look forward to

building on this year's achievements in the months ahead. Our goal must

remain a roof over the head of every Californian at a price they can

afford."

AB 1515 (Daly) allows housing projects to be afforded the protections of

the Housing Accountability Act if the project is consistent with local

planning rules despite local opposition.

"The Housing Accountability Act fosters and respects responsible local

control by providing certainty to all stakeholders in the local approval

process, and preventing NIMBYism from pressuring local officials into

rejecting or downsizing compliant housing projects," said Assembly

member Tom F. Daly (D-Anaheim). "AB 1515 strengthens the provisions

of the HAA and provides courts with clear standards for interpreting the

HAA in favor of building housing."

AB 1521 (Bloom/Chiu) gives experienced housing organizations a first

right of refusal to purchase affordable housing developments in order to

keep the units affordable.

Housing

Accessory

Dwelling

Units

Tightens Up Existing

Law to reduce local

barriers to the

development of ADU’s

C.A.R. Sponsored

Legislation

This is a follow up law to the 2016 law, AB 2299, which among other

things created a single standard for the Accessory Dwelling Unit

(ADU) permit review process regardless of whether a local

government has adopted an ordinance or not. This new law made

clarifying changes to better reflect the intent of AB 2299 including:

ADUs may be rented out; parking requirements cannot exceed one

parking space per unit or per bedroom whichever is less and; and

that “tandem parking” means when two or more cars are lined up

behind one another.

In 2016, AB 2299 made a number of changes to state law in order to

ease some of the local barriers to the development of ADUs. These

changes were numerous and included reorganizing existing law to apply

one standard for the ADU permit review process regardless of whether a

local government has adopted an ordinance or not, changing specified

ADU building and parking standards, and placing limitations on utility

connection fees and capacity charges and requirements. However, there

is a need for additional clarifying language to better reflect the intent of

AB 2299.

This law makes several changes to ADU law, which include among

others:

1) Provides that a local agency's ADU ordinance shall include that the

ADU may be rented separate from the primary residence, but may not

be sold or otherwise conveyed from the primary residence.

2) Provides that parking requirements for ADUs not exceed one parking

space per unit or per bedroom, whichever is less.

3) Removes the option for local agencies to prohibit offstreet parking in

setback areas or through tandem parking where that parking is not

allowed anywhere else in the jurisdiction.

4) Defines "tandem parking" as two or more automobiles that are parked

on a driveway or in any other location on a lot, lined up behind one

another.

5) Provides that no setback shall be required for an existing garage that

is converted to a portion of an ADU.

Assembly Bill 494 and Senate Bill 229 codified as Government Code §

65852.2.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

No Prohibition of

Efficiency Units near

school or transport

Prohibits a city, county, or city and county from limiting the number

of efficiency units in certain locations near public transit or

university campuses.

This law prohibits local governments from placing limitations on the

number of efficiency units within one-half mile of public transit, or where

there is access to a ride sharing car within one block, or within one mile

of a University of California or California State University campus. The

sponsor offered examples of several local ordinances that set a higher

square footage for efficiency units and in some cases limit the total

number of efficiency units either by percentage of the building or by

placing a cap on the total number of efficiency units in a jurisdiction. This

law preempts those ordinances. A developer seeking approval for

efficiency units would have to go through the building approval process

including an environmental review or any conditional use permit required

for the building.

Efficiency units have a minimum floor area of 150 square feet and may

also have partial kitchen or bathroom facilities

Assembly Bill 352 codified as Health and Safety Code § 17958.1.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Housing

Affordable Housing

Authorities

Allows for a city or county to create an affordable housing authority

which encompasses the entire city or county

Authorizes a city or county to adopt a resolution creating an affordable

housing authority with boundaries that may be identical to the city or

county. The authority must sunset in 45 years and is required to use its

resources to increase, improve, and preserve the community’s supply of

affordable housing. C.A.R. supported AB 1598 after it was amended to

add “workforce housing” – defined as available to 120% AMI - to the

types of housing that may be preserved and created under this authority.

Assembly Bill 1598 codified as Government Code § 62250 et seq.

Effective January 1, 2018.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)