A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Showing posts with label First Amendment. Show all posts

Showing posts with label First Amendment. Show all posts

Tuesday, July 16, 2019

How to Become a Dangerous Person

How do you become “dangerous”? Writer and Portland-based podcaster Nancy Rommelmann would have thought she was the last person to answer that question — until she publicly dared to raise some questions about the #MeToo movement. Then her life suddenly changed and she became public enemy number one. She tells her astonishing story — what happened and why — in this compelling video

Monday, July 8, 2019

Friday, May 10, 2019

‘Creepy tech oligarchs want to dictate your opinions’

‘Creepy tech oligarchs want to dictate your opinions’

Paul Joseph Watson on being banned from Facebook.

SPIKED

10th May 2019

Share

TopicsFREE SPEECH SCIENCE & TECH UK USA

Paul Joseph Watson’s sardonic YouTube monologues against social-justice warriors, mass immigration and modern art have racked up millions of views and have even caught the attention of President Donald Trump. Last week, Facebook designated Watson a ‘dangerous individual’ and banned him permanently, alongside others on the right. spiked caught up with this ‘dangerous individual’ to find out more about social-media censorship.

spiked: How did you find out you had been banned from Facebook?

Paul Joseph Watson: I received no notification whatsoever from Facebook. Facebook did not even send me a stock email to tell me my page had been deleted. I found out about it by media reports. I was on Twitter trawling through my feed. I saw CNN: ‘Paul Joseph Watson, Laura Loomer and Milo Yiannopoulos have been banned.’ I thought, ‘Oh, really?’. I checked my Facebook and my Instagram and they were still up. They were still active for about half an hour after the first media reports came out. So immediately that tells you that they had given the story to the media, to get their justification out ahead of time, so that they could own the narrative.

They gave the story to the same media outlets like CNN, where their journalist Oliver Darcy has spent the past 18 months lobbying the social-media firms to ban CNN’s competition. People like Darcy have been abusing their platform and acting as activists rather than journalists, going to Facebook, YouTube and Twitter and saying repeatedly, ‘Oh, doesn’t this post violate your policy? Doesn’t thisviolate your policy?’.

It’s not just Darcy. There is also the likes of Jared Holt at Right Wing Watch and Will Sommers at the Daily Beast, who have been very successful in silencing a great percentage of the online people who were instrumental in getting Trump elected. This has never been about ‘bullying’, ‘harassment’ or ‘hate’, whatever those mean; it’s about them fomenting this political purge ahead of the 2020 elections.

spiked: Are you a ‘dangerous individual’?

Watson: Haha! If I’m dangerous to society, then that is an illustration of how coddled, pathetic and cowed Western society has become. Mark Zuckerberg, who basically now controls the feeds of 2.4 billion people, is now setting up a Chinese-style social-credit score in the West. In tandem with these bans, Facebook has said that anyone who posts an Infowars link without condemning it could have that post removed – and even their account could be removed. This is a creepy oligarch who controls a platform with a third of the planet’s entire population and wants to dictate what thoughts and opinions can be expressed.

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are basically monopolies. They are the new public square. Outside of those three, there are few other options. I would argue that concentrating so much power into the hands of so few corporate entities and so few billionaire oligarchs like Mark Zuckerberg is a far bigger danger than my snarky Facebook posts or my video rants about modern art and brutalist architecture.

spiked: What do you think led to the ban?

Watson: I don’t think there’s any specific thing that winds them up, it’s just that I’m effective. Gavin McInnes is banned on Twitter. James Woods is currently suspended on Twitter. Laura Loomer and Milo are obviously banned. But David Duke – literally of the KKK – is still on Twitter. Richard Spencer, the leader of the actual alt-right, who believes in an ethnostate – he’s still on Twitter. If you’re not effective or your audience is fringe, you’re allowed to continue to exist on these platforms. They only really target people who are effective.

Again, that comes down to the fact that a lot of these digital media outlets like Buzzfeed, Vice, and even now CNN, are having to do hundreds of layoffs. They are basically trying to pick off their competition because before all these bans came into place, we were absolutely creaming them in terms of social-media, traffic, exposure, impressions and YouTube views. A lot of it is to do with money. They’re not only politically purging people – they are all in line with Hillary Clinton and the Democrats – but also trying to eliminate their competition because they are sinking financially.

These journalists and activists are basically pursuing their petty vendettas. They get into spats on Twitter – I used to do that way more than I do now! – and as soon as they get into these spats, they know that they have the power to get these social-media giants to silence their personal enemies. It’s a vindictive, petty little effort to shut down anyone who calls them out on social media.

spiked: Are big corporates now a bigger threat to free speech than the government?

Watson: Here in the UK, we have very sensitive laws about hate speech. Thousands of people are arrested for tweets and social-media posts each year – and I rail against that. But I have never been investigated by any UK authority for posting anything offensive or for anything hate-speech related. I have no criminal record. So the UK government doesn’t deem me to be dangerous, but Facebook does. The UK government can’t dictate what websites I can go on and where I can post. The way these corporations are ringfencing acceptable opinion is much more dangerous.

Now you have these ‘dangerous’ people. You can’t associate with them, you can’t have your picture taken with them, you can’t appear on a podcast with them, and it carries over on to other social networks. So you end up self-censoring. I had been self-censoring, anyway. And you become increasingly enclosed inside these ringfenced ideas of what is acceptable opinion because of the way these social-media giants behave.

These companies have far too much power. I’m not a libertarian or an anarchist. I do believe in some kind of government regulation. Private companies can’t just do what they like. Just as you can’t refuse service to someone just because they’re black, I don’t think you should be able to refuse service to someone because of their political views, unless they have posted something which is criminal or a direct incitement to violence (which I never did.)

We have a situation now where you have a Russian app called Telegram and its founders are saying they will not enforce codes of political correctness and will not ban users. That’s the sad state of free speech in the West. To have actual free speech – and yes, sometimes it is a little bit offensive (oh my God, the horror!), sometimes a little bit mischievous – you literally have to use a Russian app. I could go on Weibo, the Chinese Communist Party app, and I’d probably survive longer on that than I would on Facebook.

spiked: Why is it so important to defend free speech online?

Watson: Free speech is the lifeblood of any free society. The problem is that the left has completely abandoned any understanding of what free speech means. As Noam Chomsky says, if we don’t believe in freedom of expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all. And yes, some people are offensive. Big deal. If we allow free speech to be completely redefined to the point where it’s only ‘free speech BUT it offends me and needs to be removed from the internet’, then that is authoritarian. History tells us that doesn’t end well.

Paul Joseph Watson was speaking to Fraser Myers.

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

Can Government Officials Have You Arrested for Speaking to Them?

Can Government Officials Have You Arrested for Speaking to Them?

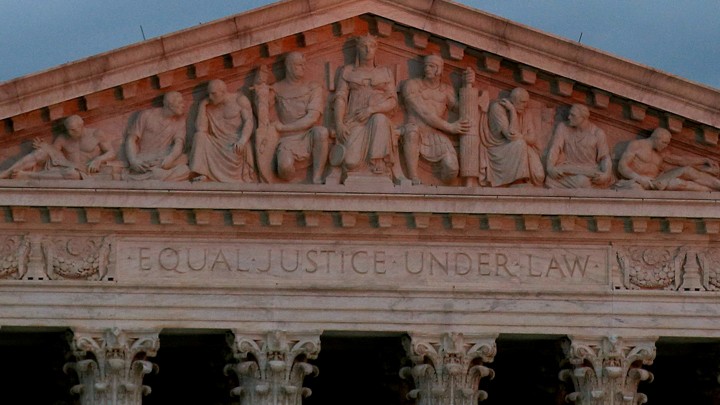

The Supreme Court faces a test of the authority of politicians to use police to silence their critics.GARRETT EPPSJAN 15, 2018

JOSHUA ROBERTS / REUTERS

JOSHUA ROBERTS / REUTERSIf a citizen speaks at a public meeting and says something a politician doesn’t like, can the citizen be arrested, cuffed, and carted off to the hoosegow?

Suppose that, during this fraught encounter, the citizen violates some law—even by accident, even one no one has ever heard of, even one dug up after the fact—does that make her arrest constitutional?

Deyshia Hargrave, meet Fane Lozman. You need to follow his case.

Hargrave is a language arts teacher in Kaplan, Louisana. She was arrested Monday after she questioned school-district policy during public comment at a school board meeting.

She asked why the superintendent of schools was receiving a five-figure raise when local teachers had not had a permanent pay increase in a decade. As she was speaking, the school-board president slammed his gavel, and a police officer told her to leave. She left, but once she went into the hall, the officer took her to the ground, handcuffed her, and arrested her for “remaining after having been forbidden” and “resisting an officer.”

Fane Lozman, whose case will be argued in front of the Supreme Court on February 27, faced the same fate at a meeting of the Riviera Beach, Florida, city council in November 2006. Lozman, remarkably enough, has made his way to the high court more or less without assistance twice in the past four years, arguing two different aspects of his acrimonious dispute with the Riviera Beach city government. The first case, which Lozman won, asked whether his motorless plywood “floating home” was actually a “vessel” subject to federal admiralty law. (Answer, via Justice Stephen Breyer: “Um, no.”) The second case is about police tactics at public meetings; its result could make a profound difference to citizens like Hargrave who want to talk back to local officials without a trip to jail.

In 2006, Lozman was living in his anchored plywood structure, which was moored at a marina in Riviera Beach. City officials planned to use eminent domain to condemn the marina site and redevelop it; Lozman sued to block the plan.

In retaliation, city officials first tried to evict him from the marina. Lozman, representing himself, argued to the jury that this was retaliation, and the jurors threw out the city’s case. The city then brought a bizarre proceeding “in admiralty” against the houseboat itself, claiming it was a “vessel” and thus subject to federal maritime law (hint: no jury). They won an order from a federal court allowing them to destroy the home. Lozman, again acting as his own lawyer, appealed the order—and in 2013 the Supreme Court reversed.

But the struggle was far from over. His original lawsuit against the city had alleged a violation of Florida’s open-meetings law. State authorities sent law enforcement agents to interview council members about those charges. The elected officials were so infuriated that, as one said on the record in a private 2006 meeting, they decided to “intimidate” Lozman and other critics “so that they can feel the same kind of unwarranted heat that we are feeling.” A few months later, Lozman went to the microphone during open comment time at a City Council meeting; but when he mentioned “public corruption” in Palm Beach County (where the city is located), the presiding council member ordered a police officer to arrest him.

He was charged with “disorderly conduct” and “resisting arrest without violence,” but the local prosecutor dropped the charges, saying in essence that no reasonable person would believe them. Lozman then brought a federal lawsuit against the city for “First Amendment retaliation.” A federal judge agreed that Lozman had “compelling” evidence that he’d been arrested as punishment for his protected speech. But the judge then threw out the case, reasoning that he actually could have been charged with the obscure state offense of “willfully interrupt[ing] or disturb[ing] any school or any assembly of people met for the worship of God or for any lawful purpose.”

What this meant, the court decided, was that the officer who arrested Lozman would have had “probable cause” (a reasonable basis to believe a crime had been committed) to arrest him if he had known about “assembly of people” statute and wanted to enforce it. The fact that the officer didn’t know about it was irrelevant—and so was the city’s unconstitutional motive. As long as an officer could have arrested Lozman for something, in other words, the retaliatory motive didn’t matter. The Eleventh Circuit affirmed: The existence of probable cause for any offense is an “absolute bar” to a suit for retaliatory arrest, it said.

If you are not a lawyer, ask yourself: Can this possibly be right? Did you by any chance violate, or do anything that might make someone think you had violated any statute, ordinance, or regulation—littering, speeding, failure to signal, improper parking, excessive use of car horn, leash-law or pet waste violation, soliciting beverage-container deposits on beverages bought out of stage, unlicensed cosmetology, unlicensed practice of geology, discharge into a storm drain, spitting on the sidewalk, barratry, champerty, maintenance, affray, seduction, or being a common scold—at any point today? Under the Eleventh Circuit’s rule (which some other circuits also use), police or officials can arrest and silence a Deyshia Hargrave when a politician wants to silence her—if, after the fact, some earnest lawyer can find a such a law, however obscure, that police at the time might have thought she was violating, even though they weren’t thinking about that.

That issue is vital to the Deyshia Hargraves of this country, as well as to dangerous offenders like Dan Heyman, a reporter arrested for asking a question of then-Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price inside the West Virginia capitol. Charges were dropped—but, if they pay no price for these tactics, local jacks-in-office will be able to silence and intimidate critics more or less at will, whether or not they are prosecuted later.

It’s established law that the First Amendment protects citizens from “adverse actions” by government, if the “adverse actions” are “retaliation” for their exercise of First Amendment rights. So a public employee who speaks to the press about a general issue of public concern can’t be fired as punishment; thus, too, officials can’t blackball government contractors for their political or partisan activities. To prove a retaliation claim, a plaintiff has to show that she engaged in protected speech and that the government retaliated because of the speech. There’s a complication, though: The government can then try to show that “the same decision would have been reached had the incident not occurred”; if it makes that showing, the plaintiff will lose.

The Supreme Court has considered a number of retaliation cases, but it has not yet explained how the “same decision” rule applies in this particular situation—when a police officer arrests someone who is speaking against government. The closest it has come is a 2006 case called Hartman v. Moore, which has actually deepened the confusion surrounding the issue.

William Moore, a tech executive, wanted to sell optical character reading equipment to the Postal Service. USPS officials favored a different system; Moore persuaded members of Congress to weigh in on his side, and eventually the USPS was barred from its favored choice. Soon after, USPS inspectors began investigating Moore, and eventually a federal prosecutor brought fraud charges against him—charges so flimsy that a District Court, after hearing six weeks of evidence, found a “complete lack of direct evidence” and tossed the charges.

Moore then sued the prosecutor and the inspectors for “retaliatory prosecution.” The Supreme Court, however, decided that such a claim—a claim that federal investigators and prosecutors had him indicted and prosecuted because of his First Amendment speech—can only succeed when the plaintiff can show complete lack of probable cause for the prosecution.

The reason is complex. To begin with, the court has held that prosecutors themselves can never be sued for the decision to prosecute a given case, no matter how mean or bone-headed. When it comes to prosecutors, courts apply a “a presumption of regularity”—that is, that “a prosecutor has legitimate grounds for the action he takes.” Because of this “absolute immunity,” a plaintiff would have to sue others in the system—in this case, the USPS inspectors—and charge that they caused the prosecutor to proceed without good reason. But if there was “probable cause,” then there was at least one good reason.

The two pieces fit together this way. First, there was probable cause; second, we assume the prosecutor was applying the law in good faith (regularity, y’now). Thus, the probable cause, not retaliation, must have been the reason for the prosecution.

But there’s an important difference between “retaliatory prosecution”—like Hartman, where prosecutors went through an indictment and a trial—and “retaliatory arrest”—where one or two law-enforcement officers arrest a person, silence them for the night, and, often as not, just let them go without charge. A prosecutor need not have been involved at all.

Nonetheless, a number of courts of appeals have concluded that Hartman bars any lawsuits for retaliatory arrest as well as prosecution—if there’s any evidence in the record of what could have been probable cause. That’s the issue the court will decide in Lozman v. Riviera Beach, Florida. It’s one that could either rein in, or embolden, the tiny-handed tyrants who rule county buildings and city halls around the country. (If you want an exhibit of the mindset at issue, consider the unrepentant Anthony Fontana, the school-board president who presided while Deyshia Hargrave was arrested. “Everybody wants to side on the poor little woman who got thrown out,” he told Fox News. “Well, she made a choice. She could have walked out and nothing would have happened.”)

Remember, plaintiffs must show that retaliation was the motive for the arrest. (In Lozman, that wasn’t hard: Meeting transcripts showed that the council wanted to “intimidate” Lozman and let him “feel the unwarranted heat.”) Unlike prosecutors, police officers don’t have immunity, and neither do elected officials who order them to silence citizens. There’s no “presumption” that an arrest is based on “legitimate grounds.”

Much of federal civil-rights law is set up to deter this kind of official bully-boy tactics. And a glimpse at any given front page in 2018 should convince even a cloistered Supreme Court justice that police attacks on free speech are still a problem.

I hope Deyshia Hargove makes her way to Washington on February 27 and sits in the Supreme Court chamber while Lozman’s lawyers argue against the kind of tactics that were used to silence her.

Of course, if she spoke up there, she’d be cuffed and arrested again; but her presence would make a statement nonetheless.

GARRETT EPPS is a contributing editor for The Atlantic. He teaches constitutional law and creative writing for law students at the University of Baltimore. His latest book is American Justice 2014: Nine Clashing Visions on the Supreme Court.

Friday, February 22, 2019

Marinwood CSD Leah Green interrupts six times and threatens arrest.

Marinwood CSD board president Leah Green threatens public with arrest and jail if "public decorum" is violated and then interrupts the public six times in two minutes during public comment time. Board president is upset that the speaker is criticizing the financial condition and issues arrest warning.

The Marin County Sheriff appears to have his hand on his gun during Leah Green's threat.

From the First Amendment to the Constitution:

The right to petition government for redress of grievances is the right to make a complaint to, or seek the assistance of, one's government, without fear of punishment or reprisals, ensured by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution (1791).

Saturday, July 8, 2017

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

Getting Hassled for Taking Pictures in San Francisco (Marinwood CSD wants to do this in Marinwood Park too)

A few years ago, the Marinwood CSD directors voted to require permits for photographing in Marinwood Park. It was voted in unanimously by the Bruce Anderson, (now NextDoor chief censor and moderator) and Leah Kleinman-Green (current CSD board member), Cyane Dandridge (promoter and consultant for the SolEd Solar project), Tarey Read and Bill Hansel.

I was the only person to object at the time, citing the county requirements for large film productions were more than adequate, but the Marinwood CSD board wanted the requirement for all photographers.

Of course, the ordinance is overly broad and virtually unenforceable. It may also be a violation of First Amendment rights. When petty politicians are in charge, no violation of common sense and decency is off limits.

At least Bruce Anderson still has NextDoor to give him a feeling of power.

Saturday, February 25, 2017

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)