Earlier this month, the American Public Transportation Association breathlessly announced that American transit systems carried more riders in 2013 than any year since 1956. The growth in ridership, said the association’s president, was evidence that Americans want more federal investments in transit.

A careful look at the association’s data, however, reveals a different story: Virtually all the increase in transit ridership from 2012 to 2013 took place in New York City. New York bus and subway ridership grew by 120 million trips in 2013; nationally, ridership grew by just 115 million trips. Outside of New York City, then, national transit ridership actually declined.

“Many rail projects marginalize poor communities and waste tax dollars.”

New York City transit ridership didn’t grow because of federal investments. Instead, a spokesman for the Metropolitan Transit Authority told The New York Timesit was a result of declining unemployment rates.

On the other hand, many cities that spent federal dollars building expensive transit projects saw falling ridership. In Portland, Ore., often cited as the model for public transit, both light-rail and bus ridership declined. Baltimore; Buffalo, N.Y.; and San Juan, Puerto Rico, also saw fewer bus and rail riders, as did urban areas with older rail systems, such as Boston and Chicago.

Furthermore, rail ridership fell in Albuquerque, N.M.; Atlanta; Houston; Minneapolis; Nashville, Tenn.; Phoenix; Sacramento, Calif.; San Francisco; and even Washington, D.C.

Rail ridership grew in Austin, Texas; Charlotte, N.C.; Dallas, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, but these cities lost more bus riders than they gained rail riders. Dallas, for example, lost four bus riders for every new rail rider; Austin lost seven; and Charlotte lost 17.

The main reason for ridership decline is that rail is expensive to build, expensive to operate and expensive to maintain. To keep trains running, transit agencies almost inevitably make cuts in bus service and raise bus fares. In 2010, the Federal Transit Administration found that the nation’s rail-transit systems suffered from a $60 billion maintenance backlog, and it has grown since then because agencies can’t even afford to keep the systems in their current state of poor repair.

|

| Opps! I guess we miscalculated! |

Regrettably, the new trains are often designed to attract middle-class travelers out of their cars, while buses are left to serve low-income neighborhoods, where people are more dependent on transit. Cuts in bus service are both unfair to transit-dependent riders and harmful to transit systems.

The NAACP even successfully sued the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority for discrimination when the agency cut bus service to black and Hispanic neighborhoods in order to cover cost overruns on its rail projects.

Only a handful of places outside of New York City saw growth in both rail and bus ridership, including Los Angeles; San Jose, Calif.; and Seattle. Previous years saw huge drops in Los Angeles and San Jose transit ridership owing to the high cost of rail. Considering that Seattle is building the most expensive light-rail line in the world — a three-mile underground route expected to cost close to $2 billion—future service cuts and overall ridership drops seem likely.

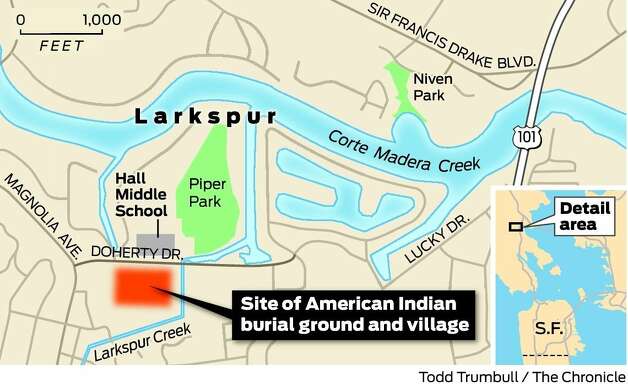

In short, far from improving transit, federal funds for building glitzy and expensive rail lines often, if not always, harm both transit systems and transit riders. Commuter trains in Dallas-Fort Worth; Nashville; and Portland, Ore., are so expensive and carry so few riders that it would have cost less (and been better for the environment) to give every daily round-trip rider a new Toyota Prius every other year for the next 30 years than to build and run the rail lines. [SMART trains in Marin will cost MORE].

The root of all these transit problems is a little-known federal fund called New Starts that gives transit agencies incentives to pick the high-cost alternative in any transit corridor. Thus, Maryland wants to build the Metro Purple Line in suburban Washington and the Red Line in Baltimore, even though environmental-impact statements for both lines say light rail will massively increase congestion and use more energy than all the cars they take off the road.

Congress should repeal New Starts and distribute the funds to transit agencies based on the number of riders they carry or fares they collect. Cities could still build rail transit lines that are truly worthwhile for their communities, but this formula would give agencies incentives to do things that boost ridership — not costs — and help transit riders in cities all over the country.