Public buses can’t compete with private automobiles because bus rides usually involve long waits, slower commutes, limited route and destination choices, and less privacy. To improve transit, it may be necessary to overhaul our current government-owned bus system by legalizing private transit services. Consider one promising alternative, “jitneys” – small private vehicles that carry passengers over regular routes but allow flexible schedules.

Public buses can’t compete with private automobiles because bus rides usually involve long waits, slower commutes, limited route and destination choices, and less privacy. To improve transit, it may be necessary to overhaul our current government-owned bus system by

legalizing private transit services. Consider one promising alternative, “jitneys” – small private vehicles that carry passengers over regular routes but allow flexible schedules.

Freely competing with buses in an unregulated transit market, jitneys can greatly increase transit riding. But open competition would let jitneys steal bus riders by interloping on established, scheduled routes. For this reason, jitneys have been almost universally banned in the United States.

Following national urban transit policy, local governments have created monopolies for scheduled bus service by prohibiting competition along given routes. Subsequently, bus operation has become highly regulated, subsidized, bureaucratized, and politicized.

We believe that jitneys and buses can coexist if government sets new rules, based on property rights, governing passenger pick-up areas. Instead of giving buses exclusive operation over routes, they should have exclusive rights only to designated bus stops, sharing routes with jitneys that have their own curb space.

We want to highlight three examples of successful jitney operations-the 1914-1916 jitneys in the United States, jitneys in less-developed countries, and current illegal jitneys in New York City. We then want to show how to introduce jitneys into the system of regulated bus transit.

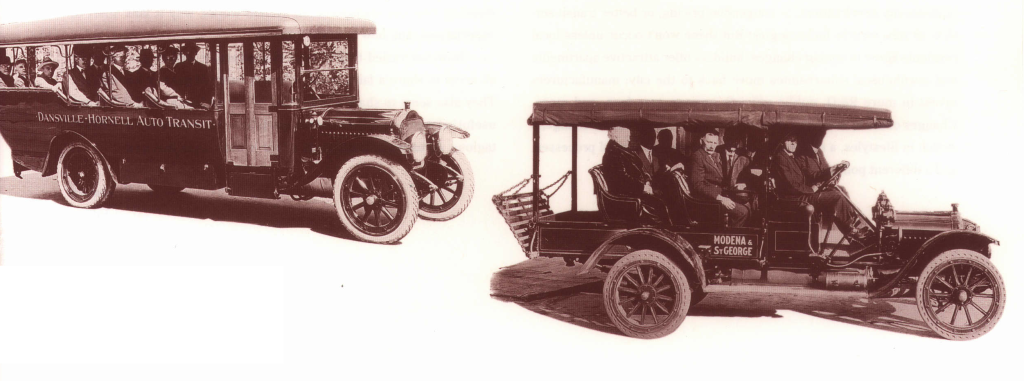

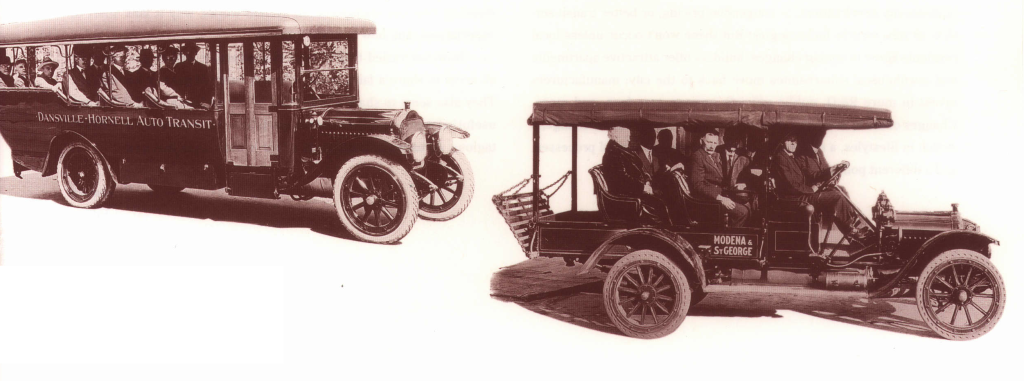

The Jitney Episode Of 1914-1916

At the tum of the century, the most popular urban transit option was the electric streetcar, which enjoyed a monopoly in the form of exclusive franchises for routes. By 1914, however, automobile owners began using their private cars to provide mass transportation. These jitneys-named after the slang term for a nickel-often ran just ahead of the streetcars, picking up waiting passengers.

Jitneys offered service comparable to private automobiles because they were quick and convenient, often providing door-to-door service. Jitney drivers operated independently. They were usually people between jobs, working part-time, or simply commuting to work themselves. They could adjust for the weather, congestion, time of day, and day of week.

Jintneys are faster and cheaper than buses, and they offer a more comfortable ride, with drivers who speak languages other than English.

By 1915, there were 62,000 jitneys operating nationwide, spurring formation of industry customs, voluntary associations, and company fleets that helped drivers obtain insurance, pay maintenance costs, and, in some cases, coordinate routes and schedules.

Jitneys undoubtedly interloped on streetcar business, yet they also filled specific market niches. People chose jitneys mainly for short distances, especially if they were not served by streetcars. The number of jitney passengers far exceeded the number of riders intercepted from streetcars, suggesting that jitneys were attracting new transit riders. But the streetcar companies saw the jitneys as infringing on their monopoly right and lobbied government to end the “jitney menace.” Municipalities gave in to their demands, in part because streetcars paid taxes and gave free transportation for police officers and fire fighters.

The 1914-1916 jitney episode illustrates the freewheeling type of transit that came with the automobile. It also introduced a fundamental issue in property rights: Does interloping on scheduled service constitute thievery? Or is it fair competition? Back then, government believed it was outright thievery. Instead of developing a framework to accommodate competitive coexistence, freewheeling transit was stamped out in favor of large-scale monopoly.

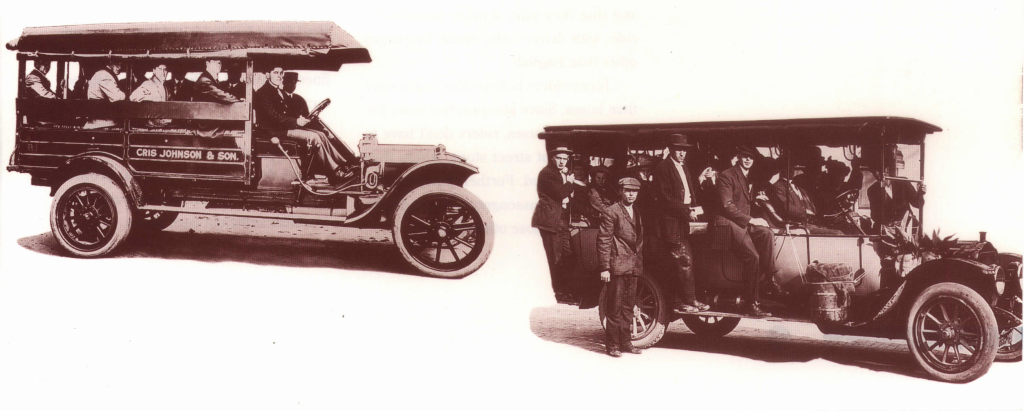

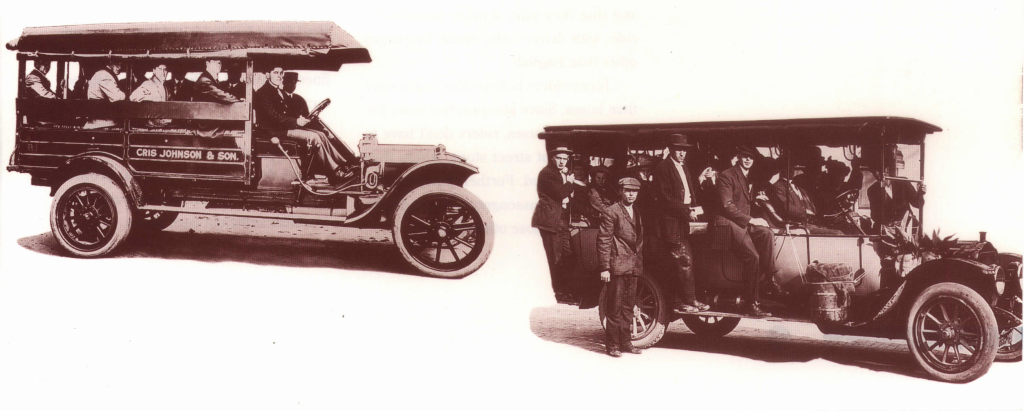

Transit in Less-Developed Countries

Jitney services similar to the early ones in the United States are operating in hundreds of cities throughout less-developed countries (LDCs) such as Peru, India, and the Philippines. There, official bus services receive subsidies, but illegal jitneys flourish by interloping on scheduled services. There are laws governing jitney safety, routes, and fares, which are meant to limit interloping; but those laws are rarely enforced.

Jitney operators often create informal route associations to regulate service with explicit rules setting routes and fares, and prohibiting interloping. The associations achieve a degree of order sufficient to control wasteful conflict among individual operators, but they also operate as a cartel. Jitneys that initially transgressed on buses’ curb rights at bus stops eventually establish curb rights for themselves. To protect those rights from new interlopers, they usually resort to physical intimidation and strong-arm tactics.

Once organized, route associations may turn to government for official recognition. After much lobbying, bribery, and petition gathering, route associations may acquire official status and receive permits or licenses. Along with official recognition, however, come political obligations and regulations – and invasion by new operators remains a threat

Ultimately, the transit history of LDCs illustrates that without curb rights – established officially or otherwise – no street transit system can survive.

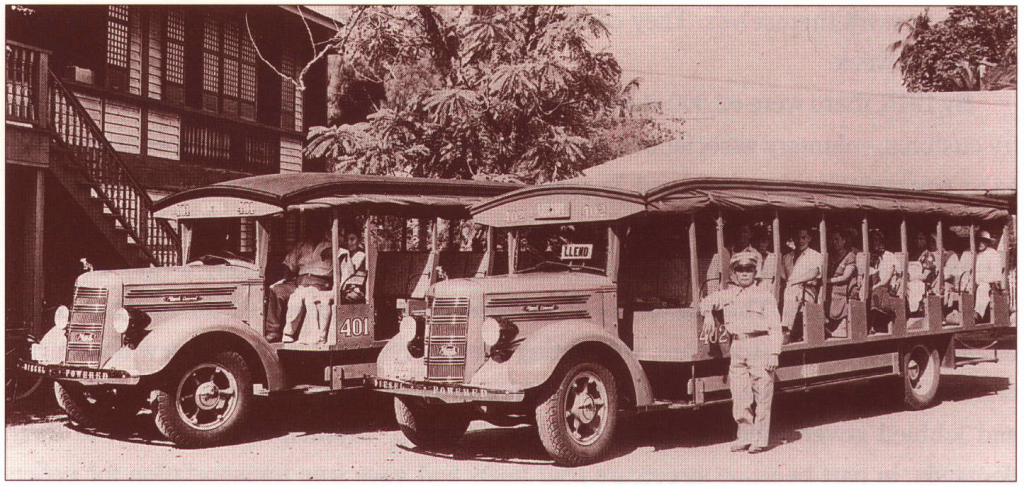

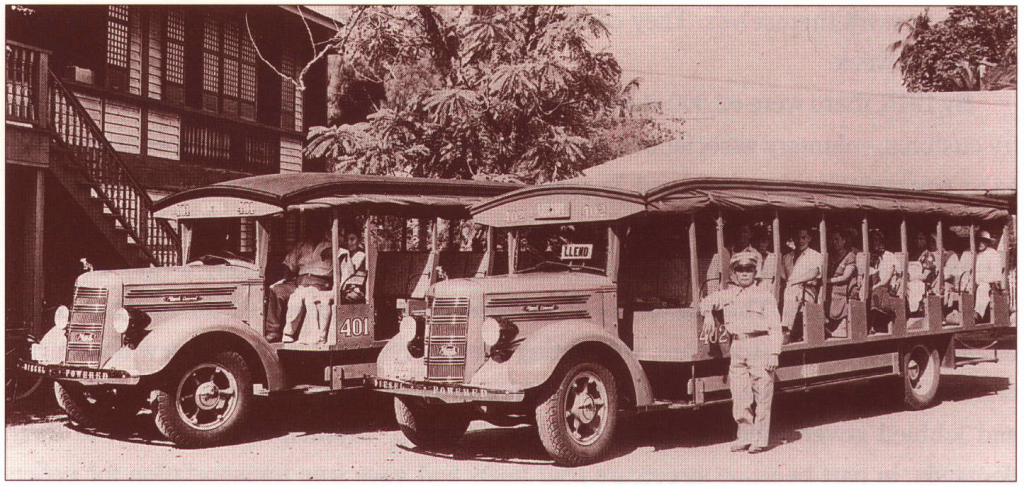

Illegal Jitneys in the United States Today

Illegal jitneys continue to operate in the United States today, most notably in New York and Miami. People who ride illegal jitneys here cite various reasons for preferring them to public buses. They say jitneys are faster and cheaper than buses and that they offer a more comfortable ride, with drivers who speak languages other than English.

Jitney riders believe jitneys are safer than buses. Since jitneys arrive more frequently than buses, riders don’t have to wait as long at street stops, where they may get mugged. Further, jitney drivers tend to reject passengers who are drunk, disorderly, or pose other threats.

Jitneys flourish in cities where transit is popular and enforcement efforts either have not succeeded or have not yet begun. In New York, modern jitney operation began during the transit strike of 1980, when illegal jitneys emerged to provide local service and feeder service to the Long Island Railroad station in Jamaica (Southeast Queens). Jitney service first developed in neighborhoods of

Caribbean immigrants, perhaps because those riders were accustomed to riding jitneys in their native land. Jitneys thrived even after bus service resumed because enforcement against them was only sporadic.

The New York Times reported that in the eighteen-month period preceding December 1991 a special task force issued 11, 773 criminal summonses against jitney operators. But jitneys remain uncontrollable, with many vans driven by Caribbean immigrants who pay little attention to the legal citations. The Wall Street journal found that over a one year period in 1990, jitneys were assessed fines of over $4 million, but the city collected only $150,000. The New York example suggests that unsubsidized private enterprise can supply fixed-route transit despite governmental prohibitions, as long as private operators can establish sufficient curb rights.

The Jitney’s Role in Different Transit Markets

The determining factor for the viability of both jitneys and buses is whether jitneys have free run of the streets and access to curbs.

As we mentioned earlier, U.S. cities typically protect bus systems from interlopers by giving them exclusive rights, or franchises, to specific routes. These rights prevent all interloping. If interloping is effectively prohibited, bus companies have an incentive to establish routes and schedules. They publicize their services and may enter new markets, trying to attract more riders, because they reap the benefits. However, giving

buses exclusive curb rights leads to inadequate competition and an inert monopoly, which may lead to low-quality service, lack of innovation, and higher fares.

In contrast, consider what happens where there are no franchised routes and no ban on competition – no exclusive rights at all – either because they are not granted or not enforced. In this case, the entire route is open to any operator. The jitney systems in LDCs and in New York City illustrate this situation. With open competition, the viability of both jitneys and buses depends on whether the market is thin (low demand) or thick (high demand).

If the market is thin, interlopers will run just ahead of scheduled buses collecting the waiting passengers and leaving few for the buses. Scheduled bus service may cease to operate due to lack of passengers. In tum, jitney riders will be less enthusiastic about congregating at the curb because they won’t have guaranteed scheduled service. Further, without scheduled service, there won’t be set arrival times at the stops. In a sense, scheduled service is the “anchor” of the market, and the entire market-buses and jitneys-may be destroyed if that anchor is dissolved.

If the market is thick, the lack of curb rights may not be a serious problem. Even without the anchor of scheduled bus service, the market may be thick enough to sustain jitneys alone. However, other problems may occur, such as low quality, irregular service, confusion over terms, and lack of trust among participants.

The choice between exclusive rights for buses or none at all poses a dilemma. Giving buses exclusive rights may create an ineffective transit monopoly, but legalizing jitneys to bring competitive energy into the market may dissolve bus service entirely. Instead of choosing either extreme, however, we propose an arrangement that takes a middle ground.

The Solution: Curb Rights

The dilemma between monopoly and anarchy can be transcended by an option that maintains limited exclusive rights for scheduled service, yet permits freewheeling competition on the route. Our solution is based on a previously unnoticed policy opportunity: creation of exclusive and transferable curb rights that allow buses and jitneys to coexist.

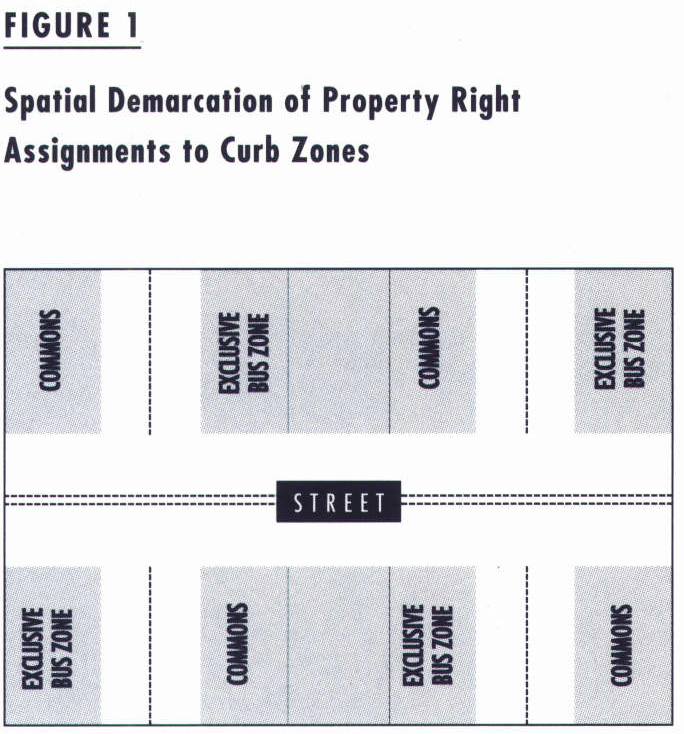

Figure 1 depicts how curb rights can include both exclusive areas for buses where their passengers congregate, and nonexclusive stops elsewhere along the route – designated as “commons” – where jitneys can pick up other passengers. These rights don’t have to be static, but can vary to accommodate the market. For example, in nonpeak hours, the commons may become additional bus-only zones.

Our scheme relies on government enforcing the designated curb rights. We think this is possible with video cameras that record illegal “trespasses.” Riders of trespassing jitneys can also be held liable, to ensure that they wait for jitneys in legal areas outside exclusive bus zones.

Further, suppose government deregulated and privatized our current bus system. If this happened, exclusive curb zones could be leased to private bus companies – either sold at set prices or auctioned off. Imagine, further, that companies may sublet or resell their leases. This may spawn an industry of curb rights: entrepreneurs who buy available curb zones, sublet rights, and manage and monitor bus stops.

Conclusion

Current transit practice grants exclusive rights to scheduled bus service, which leads to monopoly. The alternative, permitting lawless competition, may destroy the market entirely.

Our proposal, which gives curb rights to both buses and jitneys, takes advantage of both transit options. It will eliminate government control and overregulation, avoid market imperfections, and rejuvenate transit entrepreneurship and innovation. Property rights for both will help assure competition between jitneys and buses, thus improving overall transit service.

legalizing private transit services. Consider one promising alternative, “jitneys” – small private vehicles that carry passengers over regular routes but allow flexible schedules.

legalizing private transit services. Consider one promising alternative, “jitneys” – small private vehicles that carry passengers over regular routes but allow flexible schedules.

Gradual densification underway in Uptown, far from the 20th century downtown. Without parking requirements, it’s unlikely lots and garages would take up so much space. (Google Maps)

Gradual densification underway in Uptown, far from the 20th century downtown. Without parking requirements, it’s unlikely lots and garages would take up so much space. (Google Maps) New “missing middle” development within biking distance of downtown. (Google Maps)

New “missing middle” development within biking distance of downtown. (Google Maps) The magic of toleration manifests itself physically in odd neighbors on W Mckinney Street: Intriguing, unconventional townhouses sit next to… (Google Maps)

The magic of toleration manifests itself physically in odd neighbors on W Mckinney Street: Intriguing, unconventional townhouses sit next to… (Google Maps)

High density office space, apartments—and yes, parking—playfully mix. A Whole Foods sits in the middle, easily accessible to pedestrians and cyclists in the surrounding area. (Google Maps)

High density office space, apartments—and yes, parking—playfully mix. A Whole Foods sits in the middle, easily accessible to pedestrians and cyclists in the surrounding area. (Google Maps)