A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Saturday, November 15, 2014

Saturday Night short films

Immersives from Adrien Servadio on Vimeo.

Případ (The Case) - 2011 from Martin Zivocky on Vimeo.

This is my graduation film from Tomas Bata University in Zlin, Czech Republic.

Trailer: https://vimeo.com/31383248

Ancients from Nicholas Buer on Vimeo.

Don't Hug Me I'm Scared: 2 from Don't Hug Me I'm Scared on Vimeo.

TIME

Fisheye from Russell Houghten on Vimeo.

This video was shot entirely with a GoPro Hero 3 camera inside of different fish bowls. I wanted to take advantage of the GoPros "Fisheye" lens and waterproof housing and make something unique to the camera.

A Sense of Place - #1: Argyll Forest Park from Max Smith on Vimeo.

toys - hey boy from LOUIS DE CAUNES on Vimeo.

Goodbye Rabbit, Hop Hop from caleb wood on Vimeo.

Friday, November 14, 2014

VIDEO: Why Affordable Housing Fails to help the Needy circa 1978

The Above video is from a lecture given by noted economist Milton Friedman to students at Cornell University. In the late seventies, the large public housing of the 1960s were widely acknowledged to be failures for various reasons Professor Friedman lists.

.

Up until a few years ago affordable housing has been integrated with market rate housing. It has been determined to be the best approach for both the families living in affordable housing and the landlords to minimize the problems associated with isolated communities of low income people.

Marinwood Lucas (5.68 square miles) is targeted for 71% of all Affordable Housing in unincorporated Marin with large 100% affordable housing complexes!

We must not only ask ourselves, "Is this the best we can do for our community?" but also ask "Is this the best we can do for the hundreds of low income families that will live among us?"

Wouldn't a strategy to integrate low income housing in ALL NEIGHBORHOODS in Marin be better for them?

Have we not learned from the failures of the past?

GET INVOLVED. CONTACT THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS. TELL THEM REVISE THE HOUSING ELEMENT.

Join us!

The FORBIDDEN House and Lifestyle you CANNOT have with Plan Bay Area

|

| Simon Dale family in Wales. |

Building Taj Mahals with Taxpayer Money

Building 'Taj Mahals' with Taxpayer Money - Voice of San Diego: Pounding The Pavement

The 226 apartments at the downtown affordable housing high-rise Ten Fifty B cost an average of nearly $400,000 to build, most of which was funded by taxpayers. More than half of those apartments are 465-square-foot studios or 648-square-foot one-bedrooms.

Related Images

File photo by Sam Hodgson

Construction workers help build an affordable housing development in Barrio Logan.

File photo by Sam Hodgson

Construction workers help build an affordable housing development in Barrio Logan.

File photo by Sam HodgsonConstruction workers help build an affordable housing development in Barrio Logan.

File photo by Sam HodgsonConstruction workers help build an affordable housing development in Barrio Logan.

Related Stories

Related Links

- PDF: Building 'Taj Mahals' with Taxpayer Money (The Game: A VOSD Investigation)

- Opinion: Affordable Housing Has Strings Attached

- Opinion: Let's Be Honest About Affordable Housing

The Game: A VOSD Investigation Key Findings • Building affordable housing in the city of San Diego today is often wildly more expensive than building private, market-rate apartment buildings. • Several recent local affordable housing projects have cost taxpayers $400,000 to $500,000 per apartment, often for tiny studios and one-bedroom units. • Designed to provide homes for those who can’t pay San Diego’s high rents, affordable housing has instead become a delivery mechanism for a host of public policy goals, from building green and near transit to offering tenants personal finance classes, all of which add cost. • Since 2007, almost $600 million in public funding has been spent building 2,134 for-rent affordable apartments units in San Diego. • The more cost a project takes on, the more likely it is to win the tough competition for lucrative taxpayer-funded grants called tax credits. • The requirement to pay “prevailing wages” significantly higher than the market rate is also credited with pushing up costs by as much as 25 percent. Unskilled workers, for example, can earn an hourly wage that's equivalent to a salary of between $72,000 and $90,000 a year. • Costs have escalated to the point that even industry players agree they've gotten out of hand. The committee that hands out tax credits acknowledges this and is holding a series of seminars around the state to figure out how to bring costs down. • Far from the ugly concrete towers of the past, today’s affordable housing projects are often the best-designed, most beautiful buildings in their neighborhoods. • The result: Far fewer affordable apartments get built in San Diego than could be.In Barrio Logan, in the shadow of the Coronado Bridge and under the watchful eyes of the Chicano Park murals, bright yellow backhoes busily cleave away the soil.It’s here, in one of San Diego’s poorest neighborhoods, that the city will get its newest government-sponsored housing project: the Estrella del Mercado, a 92-unit apartment building that will sit above shops and restaurants and adjacent to a Latino-themed supermarket, all part of the Mercado del Barrio development.

The project has been a long time coming. The community waited for more than two decades while local government agencies put together one deal after another, only to watch those projects fall apart without a single hole being dug or nail being nailed.

The waiting list for the new apartments will grow to thousands of names, as families clamor for a chance to rent a sparkling new home at the edge of downtown for greatly reduced rates. Project boosters say it will breathe new life into a blighted area, increase tax revenues and entice private developers to invest in an overlooked neighborhood.

But along with the public benefit, the project also comes with a hefty price tag for taxpayers.

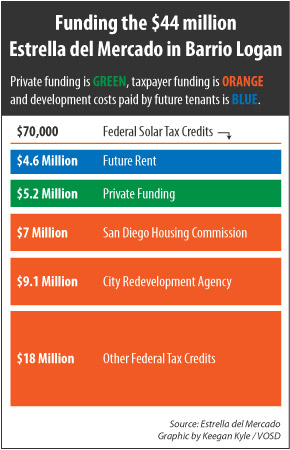

The $44 million apartment project will cost an average of $477,743 per unit, 90 percent of which will be paid by taxpayers. That’s twice what private developers say they’re spending to develop high-end apartments in the city today.

A few miles away, in Mission Valley, a private developer said he’s building top-shelf apartments for $225 a square foot. Another developer currently building upscale apartments downtown said his total cost is $275 a square foot.

The Estrella del Mercado apartments will cost $529 a square foot.

Taxpayers have poured almost $600 million into two dozen housing projects in the city of San Diego since 2007. A three-month voiceofsandiego.org investigation showed that, again and again, these projects are wildly more expensive than private developments.

Affordable housing is designed to provide homes for tens of thousands of working families who can’t afford to pay San Diego’s high rents. But with tens of millions of tax dollars set aside each year to build it, affordable housing in California has also evolved into a delivery mechanism for social goals that have little to do with that central mission — and even less to do with containing costs.

The result: Far fewer affordable apartments get built in San Diego than could be.

Today, many in the affordable housing industry describe their business simply as “The Game,” in which a core cadre of developers partner with government allies to build increasingly elaborate and expensive buildings in a lucrative, high-stakes competition funded by taxpayers.

“It’s just gotten out of hand,” said Tom Scott, former executive director of the San Diego Housing Federation, a coalition of affordable housing advocates and developers. “We need to re-evaluate where we’re headed with these public policy goals and recognize there’s a need to create as many units as we can, without just warehousing people.”

Far from the ugly concrete towers of the past, today’s affordable housing projects are often the best-designed, most beautiful buildings in their neighborhoods.

Click on the graphic above to view cost information

for all city affordable housing projects approved since

January 2007.

Developers and public agencies have been squeezed by increasingly restrictive regulations to construct buildings that aren’t just cheap to rent but also have exclusive features like solar panels, biodegradable carpets and free high-speed internet. They’ve been ordered to build in dense urban neighborhoods, where often the only scraps of land left are expensive-to-develop parcels already spurned by the private sector.

Add in the requirement to pay much higher wages than the market dictates, which can boost a project’s cost by as much as 25 percent, and the net effect of decades of government tinkering has been to add substantially to the cost of building affordable housing.

As local governments scrounge around for spare change to keep basic services like schools, libraries and public safety afloat, tens of millions of dollars remain locked down for the sole purpose of funding the affordable housing game.

That money could be spent doing what private developers are doing: Constructing different types of buildings that house perfectly nice high-end apartments and cost $200,000 to $275,000 per unit. But in San Diego it is often instead spent building what industry insiders derisively call “Taj Mahals” — beautiful places for a lucky few to live cheaply but that cost taxpayers dearly.

The Game

Photo by Sam Hodgson Jim Schmid, CEO of Chelsea Investment Corp., which is developing the Estrella del Mercado affordable apartments in Barrio Logan, says the cost of developing affordable housing in San Diego is out of control.

Affordable housing has been around in California for decades. Unlike private development, government-sponsored building has proven immune to the housing crisis, and some of the only apartments built in San Diego over the last few years have been affordable housing projects.

The concept has always been simple: Use government dollars to provide apartments to residents at subsidized rents.

City agencies lend private developers public money and help them get access to lucrative taxpayer-funded grants called tax credits. In exchange, the developers promise to limit rents in their buildings to levels dictated by the area’s median income.

The cheapest one-bedroom apartment in the Estrella del Mercado, for example, will rent for $460 a month, compared to a citywide average of $1,162, according tothe latest study by the San Diego County Apartment Association.

To qualify for that one-bedroom apartment, tenants must be able to prove they earn less than 30 percent of the area median income, which currently equals $17,310 a year for an individual or $24,720 for a family of four.

Every year, the state of California requires each county to build a certain amount of affordable housing. San Diego County divides that mandate among local cities and much of the burden falls on the city of San Diego.

Since January 2007, city agencies have subsidized the building of 2,134 apartments stretching from San Ysidro to Rancho Bernardo. That’s a drop in the bucket in a city with almost 240,000 rental properties, and where one local analyst estimates that 56 percent of renters, around 134,000 households, live in housing they can’t afford.

The cash for those projects came from a web of taxpayer-funded sources.

In some areas like downtown and southeastern San Diego, government redevelopment agencies have to spend 20 percent of the property taxes they receive to build affordable housing. Last year, city taxpayers paid $55 million into that fund. Developers in San Diego also have to build 10 percent of their homes affordable or pay into another city fund used to subsidize affordable housing.

Then there are tens of millions of dollars handed out each year in federal and state low-income tax credits. Those are given to developers who can prove their project’s worth to a powerful three-person committee made up of the state treasurer, controller and finance director.

The competitive process of convincing that Sacramento triumvirate to hand over tax credits is often cited as the chief culprit driving up the cost of building affordable housing in California today.

Developers spend months putting together applications that are often inches thick and that break down their projects to the finest detail. The trick is to score as high as possible on the committee’s points system, a process that during the last decade has become increasingly daunting and has resulted in escalating bills for taxpayers, who eventually foot the cost.

A Beauty Pageant

Photo by Sam Hodgson Residents of the affordable housing development Ten Fifty B enjoy such accoutrements as this fire pit, which overlooks the downtown skyline.

Developers know one thing when they head before the group known formally as the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee: The more cool features they can add to their project, the more likely it will win the competitive battle.

The winner-takes-all beauty pageant has become one of the major avenues for injecting public policy into affordable housing.

Build in urban areas near schools and transit, get points. Add in a community room, computers and evening classes on personal finance, get more points. Build green, bingo.

“The more you actually build — the more cost you take on on a project — the more competitive you’re gonna be,” said Robert Chavez, the city official overseeing the Mercado del Barrio project.

All those bells and whistles add cost to the project. But the final cost of building each apartment has become almost an afterthought in determining who gets tax credits.

While building more wins a developer points, there’s little incentive to build cheap, and the per-unit cost of a project is never considered in the committee’s points system.

The result: Price tags like $423,000 per unit for El Pedregal Family Apartments, a 45-unit project in San Ysidro, and $511,000 per unit for Cedar Gateway, currently under construction downtown. Both got perfect scores from the committee and both also got extra points because they secured additional loans from local public agencies, which kicked in millions to make the deals happen.

Jeanne Peterson, who now works as a Sacramento accountant, helped create the points system in the early 2000s. She said some criteria, such as building near schools and medical centers, sounded like good ideas at the time but have added so much cost they’ve backfired.

“There are brokers now that even advertise that their land meets the requirement for tax credits, so they charge much higher prices, which drives costs up,” said Peterson, who was the committee’s executive director from 1999 to 2004. “The system is not discouraging projects from having escalating costs.”

That hasn’t gone unnoticed by the committee. In an interview last month, Bill Pavão, the committee’s current executive director, who manages tax credits for State Treasurer Bill Lockyer, said the committee was assessing how to put cost front-and-center in its decision-making process.

“We’ve recognized that there’s a point when these prices have just spiraled out of control,” Pavão said.

Last week, the committee announced it will be holding a series of forums around the state to discuss how to contain costs on projects it funds. Projects receiving tax credits “generally may be more costly than necessary, fostering the public perception that affordable housing is too expensive,” read an announcement on the committee’s website.

Building Taj Mahals

Photo by Sam Hodgson The lobby of Ten Fifty B is adorned with curved, sculpted benches and boasts its green credentials along the walls.

The lobby of Ten Fifty B looks more like the entrance to a modern, upmarket hotel than the gateway to an affordable housing project.

Curved benches, sculpted from individually carved pieces of wood, sit under soft mood lighting. Along one wall, a glowing recycled panel flecked with inlaid pine needles and twigs lists the building’s sustainability achievements: gold LEED certification, rooftop solar panels, biodegradable carpeting and low-emission organic paints. Outside the front door, there’s a living wall inlaid with cacti and other plants.

It’s still tough sometimes for affordable housing boosters to convince neighborhoods to accept their projects. The buildings come with a stigma and community planning groups and neighbors often campaign hard against them.

So to ingratiate projects into unwelcoming neighborhoods, developers often conceive buildings that are architecturally and aesthetically superior to anything else on the block.

Building stunning real estate serves another stated purpose of the agencies tasked with creating affordable housing: eliminating blight in run-down neighborhoods that have been designated as redevelopment areas.

But building beautiful doesn’t come cheap. By the time it opened last year, each of the 226 apartments at Ten Fifty B had cost taxpayers almost $400,000. More than half of those apartments are 465-square-foot studios or 648-square-foot one-bedrooms.

Kent Robertson, a Santa Ana consultant, has surveyed hundreds of private and public projects as a cost evaluator for lenders, investors and developers. He said affordable housing projects almost always have expensive architectural features for “100 percent aesthetic reasons.”

“The architect is just let go,” Robertson said. “He’s creating a resume-boosting building.”

Affordable housing developers pointed out that building sustainable, durable buildings saves money in the long run, however.

Jim Silverwood, president of Affirmed Housing Group, which developed Ten Fifty B, said including all the cutting-edge sustainability elements into his building cost less than 1 percent of the total construction price. The energy cost savings over the life of the project will pay for that many times over, he said.

And buildings like Ten Fifty B are built durable because they’re government investments designed to last at least the 65 years they’ll remain affordable, Silverwood said.

A Bigger Paycheck, a Higher Cost

Photo by Sam Hodgson Workers at the Mercado del Barrio construction site make a government-mandated “prevailing wage,” which drives up project costs by as much as 25 percent.

For the average construction worker in San Diego, an affordable housing project represents more than a stable job for a few weeks or months. It also means a significantly fatter paycheck.

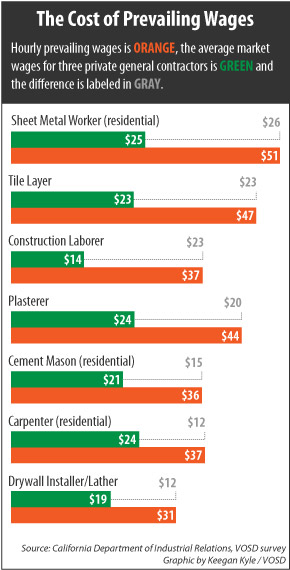

Contractors on most government projects are required to pay their workers “prevailing wages,” which in California are set by the Department of Industrial Relations and typically reflect wage levels set by labor unions. On San Diego construction sites, where many workers are not unionized, the requirement to pay prevailing wages can make a big difference both to workers and to project costs.

Unskilled workers on the Mercado del Barrio project construction site, for example, will be paid between $35 and $44 an hour for performing basic tasks like sweeping and digging holes. That’s equivalent to $72,000 to $92,000 a year.

A survey of three local general contractors who do private development showed they pay unskilled workers or laborers more like $14 an hour.

Four affordable housing developers said prevailing wages push development costs up by 20 to 25 percent. Jim Schmid, CEO of Chelsea Investment Corp., which is developing the Estrella del Mercado, said that means 20 to 25 percent fewer affordable apartments get built.

“We have many projects with a thousand people on the waiting list,” he said. “If the units cost less we could build more of them and more San Diegans could live in an affordable home.”

But supporters of prevailing wages said paying workers at the lower end of the spectrum would create a paradox: Building more affordable housing while at the same time creating more people who need government-subsidized apartments.

Prevailing wages help give unskilled laborers a financial boost so they can rise into the middle class, said Susan Tinsky, current executive director of the San Diego Housing Federation.

“We should have a holistic approach and we shouldn’t be perpetuating public policy problems when we spend our public dollars,” she said.

‘Just Absurd’

Photo by Sam Hodgson The City Council approved construction of 24 apartment units on El Cajon Boulevard in October 2007. The North Park project, known as the Boulevard Apartments, was budgeted to cost $11.6 million, or $506,609 per unit.

In a private real estate development deal, the profit comes in a tangible form: Dollars and cents.

Private developers decide what and where to build by surveying the market and seeing what makes sense financially — what’s going to make them the most money. That means weighing the future income they can make from a project against all the cost that go into developing it.

In pure economic terms, today’s affordable housing projects don’t fare well in that equation.

“It’s just absurd to pay $400,000 for a studio. You could be buying every family a 5,000 square-foot house in Eastlake for that,” said Steve Huffman, a real estate broker who regularly sells local apartment buildings.

But in the affordable housing game, profits are a more amorphous beast. The value an affordable apartment building will bring to the community comes in hard-to-measure forms like the elimination of a blighted block or, in a mixed use project like the Mercado del Barrio, the creation of a development meant to give a neighborhood a vibrant nucleus.

These benefits of planned affordable housing projects are discussed at length in community meetings, committees, staff meetings and, eventually, in a public meeting of the San Diego City Council, the ultimate arbiter for deciding which projects get city funding.

But the other side of the equation, how much the projects actually end up costing the taxpayer, is almost never talked about.

A stark example is the Boulevard Apartments in North Park, a 24-unit project that looks out across El Cajon Boulevard’s smoke shops and check-cashing centers.

The building, which opened in 2009, is extraordinary in local affordable housing for another reason than its total development budget of $485,500 an apartment: Somebody at a local public agency criticized the project’s high per-unit cost in the run-up to its approval.

In hundreds of pages of reports, analyses and financial documents on the projects examined for this story, concern over a project’s high per-unit cost appeared just once: A city Redevelopment Agency report prepared for a City Council meeting to discuss the project, says its loan committee recommended not approving the subsidy “due to the concern that the total cost per unit appears high in comparison to other projects.”

That one sentence, in a report that otherwise waxes lyrical about the project, never made it into the final discussion of the Boulevard Apartments, which took place at the Oct. 30, 2007 City Council meeting.

Then-Council President Scott Peters introduced the item.

“Can you give us three or four sentences on why it’s so great?” Peters asked then-Councilwoman Toni Atkins, in whose district the apartments were to be built.

Atkins then did just that. Just more than a minute later, the $11.6 million project was approved unanimously.

The whole discussion, from introduction to final vote, lasted about 90 seconds.

Correction: This story originally stated that the budgeted per-unit cost of the Boulevard Apartments was $506,609. That figure neglected to take into account the manager’s apartment, which was not designated affordable. When that unit is factored in, the per-unit cost is actually $485,500. We’ve also updated it to include 983 square feet of internal common area for the Estrella del Mercado, which we did for other projects, and to reflect a slightly larger rentable square footage area for the building based on more recent plans. That changed the square-foot development cost from $542 to $529.We regret the errors.

Please contact Will Carless directly at will.carless@voiceofsandiego.org or at 619.550.5670 and follow him on Twitter: twitter.com/willcarless.

Voice of San Diego is a nonprofit that depends on you, our readers. Please donate to keep the service strong. Click here to find out more about our supporters and how we operate independently.

Value investigative reporting? Support it. Donate Now.

Will Carless is the former head of investigations at Voice of San Diego. He currently lives in Montevideo, Uruguay, where he is a freelance foreign correspondent and occasional contributor to VOSD. You can reach him at will.carless.work@gmail.com.

Will Carless is the former head of investigations at Voice of San Diego. He currently lives in Montevideo, Uruguay, where he is a freelance foreign correspondent and occasional contributor to VOSD. You can reach him at will.carless.work@gmail.com.

- PDF: Building 'Taj Mahals' with Taxpayer Money (The Game: A VOSD Investigation)

- Opinion: Affordable Housing Has Strings Attached

- Opinion: Let's Be Honest About Affordable Housing

| The Game: A VOSD Investigation |

| Key Findings |

| • Building affordable housing in the city of San Diego today is often wildly more expensive than building private, market-rate apartment buildings. |

| • Several recent local affordable housing projects have cost taxpayers $400,000 to $500,000 per apartment, often for tiny studios and one-bedroom units. |

| • Designed to provide homes for those who can’t pay San Diego’s high rents, affordable housing has instead become a delivery mechanism for a host of public policy goals, from building green and near transit to offering tenants personal finance classes, all of which add cost. |

| • Since 2007, almost $600 million in public funding has been spent building 2,134 for-rent affordable apartments units in San Diego. |

| • The more cost a project takes on, the more likely it is to win the tough competition for lucrative taxpayer-funded grants called tax credits. |

| • The requirement to pay “prevailing wages” significantly higher than the market rate is also credited with pushing up costs by as much as 25 percent. Unskilled workers, for example, can earn an hourly wage that's equivalent to a salary of between $72,000 and $90,000 a year. |

| • Costs have escalated to the point that even industry players agree they've gotten out of hand. The committee that hands out tax credits acknowledges this and is holding a series of seminars around the state to figure out how to bring costs down. |

| • Far from the ugly concrete towers of the past, today’s affordable housing projects are often the best-designed, most beautiful buildings in their neighborhoods. |

| • The result: Far fewer affordable apartments get built in San Diego than could be.In Barrio Logan, in the shadow of the Coronado Bridge and under the watchful eyes of the Chicano Park murals, bright yellow backhoes busily cleave away the soil.It’s here, in one of San Diego’s poorest neighborhoods, that the city will get its newest government-sponsored housing project: the Estrella del Mercado, a 92-unit apartment building that will sit above shops and restaurants and adjacent to a Latino-themed supermarket, all part of the Mercado del Barrio development. |

The project has been a long time coming. The community waited for more than two decades while local government agencies put together one deal after another, only to watch those projects fall apart without a single hole being dug or nail being nailed.

The waiting list for the new apartments will grow to thousands of names, as families clamor for a chance to rent a sparkling new home at the edge of downtown for greatly reduced rates. Project boosters say it will breathe new life into a blighted area, increase tax revenues and entice private developers to invest in an overlooked neighborhood.

But along with the public benefit, the project also comes with a hefty price tag for taxpayers.

The $44 million apartment project will cost an average of $477,743 per unit, 90 percent of which will be paid by taxpayers. That’s twice what private developers say they’re spending to develop high-end apartments in the city today.

A few miles away, in Mission Valley, a private developer said he’s building top-shelf apartments for $225 a square foot. Another developer currently building upscale apartments downtown said his total cost is $275 a square foot.

The Estrella del Mercado apartments will cost $529 a square foot.

Taxpayers have poured almost $600 million into two dozen housing projects in the city of San Diego since 2007. A three-month voiceofsandiego.org investigation showed that, again and again, these projects are wildly more expensive than private developments.

Affordable housing is designed to provide homes for tens of thousands of working families who can’t afford to pay San Diego’s high rents. But with tens of millions of tax dollars set aside each year to build it, affordable housing in California has also evolved into a delivery mechanism for social goals that have little to do with that central mission — and even less to do with containing costs.

The result: Far fewer affordable apartments get built in San Diego than could be.

Today, many in the affordable housing industry describe their business simply as “The Game,” in which a core cadre of developers partner with government allies to build increasingly elaborate and expensive buildings in a lucrative, high-stakes competition funded by taxpayers.

“It’s just gotten out of hand,” said Tom Scott, former executive director of the San Diego Housing Federation, a coalition of affordable housing advocates and developers. “We need to re-evaluate where we’re headed with these public policy goals and recognize there’s a need to create as many units as we can, without just warehousing people.”

Far from the ugly concrete towers of the past, today’s affordable housing projects are often the best-designed, most beautiful buildings in their neighborhoods.

|

| Click on the graphic above to view cost information for all city affordable housing projects approved since January 2007. |

Developers and public agencies have been squeezed by increasingly restrictive regulations to construct buildings that aren’t just cheap to rent but also have exclusive features like solar panels, biodegradable carpets and free high-speed internet. They’ve been ordered to build in dense urban neighborhoods, where often the only scraps of land left are expensive-to-develop parcels already spurned by the private sector.

Add in the requirement to pay much higher wages than the market dictates, which can boost a project’s cost by as much as 25 percent, and the net effect of decades of government tinkering has been to add substantially to the cost of building affordable housing.

As local governments scrounge around for spare change to keep basic services like schools, libraries and public safety afloat, tens of millions of dollars remain locked down for the sole purpose of funding the affordable housing game.

That money could be spent doing what private developers are doing: Constructing different types of buildings that house perfectly nice high-end apartments and cost $200,000 to $275,000 per unit. But in San Diego it is often instead spent building what industry insiders derisively call “Taj Mahals” — beautiful places for a lucky few to live cheaply but that cost taxpayers dearly.

The Game

Affordable housing has been around in California for decades. Unlike private development, government-sponsored building has proven immune to the housing crisis, and some of the only apartments built in San Diego over the last few years have been affordable housing projects.

The concept has always been simple: Use government dollars to provide apartments to residents at subsidized rents.

City agencies lend private developers public money and help them get access to lucrative taxpayer-funded grants called tax credits. In exchange, the developers promise to limit rents in their buildings to levels dictated by the area’s median income.

The cheapest one-bedroom apartment in the Estrella del Mercado, for example, will rent for $460 a month, compared to a citywide average of $1,162, according tothe latest study by the San Diego County Apartment Association.

To qualify for that one-bedroom apartment, tenants must be able to prove they earn less than 30 percent of the area median income, which currently equals $17,310 a year for an individual or $24,720 for a family of four.

Every year, the state of California requires each county to build a certain amount of affordable housing. San Diego County divides that mandate among local cities and much of the burden falls on the city of San Diego.

Since January 2007, city agencies have subsidized the building of 2,134 apartments stretching from San Ysidro to Rancho Bernardo. That’s a drop in the bucket in a city with almost 240,000 rental properties, and where one local analyst estimates that 56 percent of renters, around 134,000 households, live in housing they can’t afford.

The cash for those projects came from a web of taxpayer-funded sources.

In some areas like downtown and southeastern San Diego, government redevelopment agencies have to spend 20 percent of the property taxes they receive to build affordable housing. Last year, city taxpayers paid $55 million into that fund. Developers in San Diego also have to build 10 percent of their homes affordable or pay into another city fund used to subsidize affordable housing.

Then there are tens of millions of dollars handed out each year in federal and state low-income tax credits. Those are given to developers who can prove their project’s worth to a powerful three-person committee made up of the state treasurer, controller and finance director.

The competitive process of convincing that Sacramento triumvirate to hand over tax credits is often cited as the chief culprit driving up the cost of building affordable housing in California today.

Developers spend months putting together applications that are often inches thick and that break down their projects to the finest detail. The trick is to score as high as possible on the committee’s points system, a process that during the last decade has become increasingly daunting and has resulted in escalating bills for taxpayers, who eventually foot the cost.

A Beauty Pageant

Developers know one thing when they head before the group known formally as the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee: The more cool features they can add to their project, the more likely it will win the competitive battle.

The winner-takes-all beauty pageant has become one of the major avenues for injecting public policy into affordable housing.

Build in urban areas near schools and transit, get points. Add in a community room, computers and evening classes on personal finance, get more points. Build green, bingo.

“The more you actually build — the more cost you take on on a project — the more competitive you’re gonna be,” said Robert Chavez, the city official overseeing the Mercado del Barrio project.

All those bells and whistles add cost to the project. But the final cost of building each apartment has become almost an afterthought in determining who gets tax credits.

While building more wins a developer points, there’s little incentive to build cheap, and the per-unit cost of a project is never considered in the committee’s points system.

The result: Price tags like $423,000 per unit for El Pedregal Family Apartments, a 45-unit project in San Ysidro, and $511,000 per unit for Cedar Gateway, currently under construction downtown. Both got perfect scores from the committee and both also got extra points because they secured additional loans from local public agencies, which kicked in millions to make the deals happen.

Jeanne Peterson, who now works as a Sacramento accountant, helped create the points system in the early 2000s. She said some criteria, such as building near schools and medical centers, sounded like good ideas at the time but have added so much cost they’ve backfired.

“There are brokers now that even advertise that their land meets the requirement for tax credits, so they charge much higher prices, which drives costs up,” said Peterson, who was the committee’s executive director from 1999 to 2004. “The system is not discouraging projects from having escalating costs.”

That hasn’t gone unnoticed by the committee. In an interview last month, Bill Pavão, the committee’s current executive director, who manages tax credits for State Treasurer Bill Lockyer, said the committee was assessing how to put cost front-and-center in its decision-making process.

“We’ve recognized that there’s a point when these prices have just spiraled out of control,” Pavão said.

Last week, the committee announced it will be holding a series of forums around the state to discuss how to contain costs on projects it funds. Projects receiving tax credits “generally may be more costly than necessary, fostering the public perception that affordable housing is too expensive,” read an announcement on the committee’s website.

Building Taj Mahals

|

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Randal O'Toole discusses Housing Crisis

Randal O'Toole, discusses how Smart Growth government policies affect housing prices

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

How Smart Growth and Livability Intensify Air Pollution

|

| More people in Marinwood-Lucas Valley means more pollution |

By Wendell Cox

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) wants to implement stronger air pollution restrictions on ozone (smog) for the stated purpose of improving public health. These regulations are misguided because they would impose significant costs for little or no benefit. At the same time, policies being implemented at the state and local levels and proposed at the federal level are working to undermine any improvement of air quality.

Population Density and Air Pollution

For years, regional transportation plans, public officials, and urban planners have been seeking to densify urban areas, using strategies referred to as “smart growth” or “livability.” They have claimed that densifying urban areas would lead to lower levels of air pollution, principally because it is believed to reduce travel by car. In fact, however, EPA data show that higher population densities are strongly associated with higher levels of automobile travel and more concentrated air pollution.[3]

This is illustrated by county-level data for nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions, which is an important contributor to ozone formation. This analysis includes the more than 425 counties in the nation’s major metropolitan areas (those with more than 1 million in population).[4] Seven of the 10 counties with the highest NOx emissions concentration (annual tons per square mile)[5] in major metropolitan areas are also among the top 10 in population density (2008). New York County (Manhattan) has by far the most intense NOx emissions and is also by far the most dense. Manhattan also has the highest concentration of emissions for the other criteria air pollutants, such as carbon monoxide, particulates, and volatile organic compounds (2002 data).[6] New York City’s other three most urban counties (Bronx, Kings, and Queens) are more dense than any county in the nation outside Manhattan, and all are among the top 10 in NOx emission density. (See Table 1.)

Traffic and Air Pollution

More concentrated traffic also leads to greater traffic congestion and more intense air pollution. The data for traffic concentration is similar to population density.[7] Manhattan has by far the greatest miles of road travel per square mile of any county. Again, seven of the 10 counties with the greatest density of traffic are also among the 10 with the highest population densities. As in the case of NOx emissions, the other three highly urbanized New York City counties are also among the top 10 in the density of motor vehicle travel. (See Table 1.) The overall relationship between higher population densities and both NOx concentration and motor vehicle traffic intensity is illustrated in Table 2. There is a significant increase in the concentration of both NOx emissions and motor vehicle travel in each higher category of population density. For example, the counties with more than 20,000 people per square mile have NOx emission concentrations 14 times those of the average county in these metropolitan areas, and motor vehicle travel is 22 times the average.[8] A smaller sample of the most urbanized counties (those with 90 percent or more of the land urbanized) showed a stronger association.[9]

Even research by the Sierra Club and a model derived from that research by ICLEI–Local Governments for Sustainability, both strong supporters of densification, show that traffic volumes increase with density.

[10] The Goal: Improving Public Health These data strongly indicate that the densification strategies associated with smart growth and livability are likely to worsen the concentration of both NOx emissions and motor vehicle travel. But there is a more important impact. A principal reason for regulating air pollution from highway vehicles is to minimize public health risks. Any public policy that tends to increase air pollution intensities will work against the very purpose of air pollution regulation—public health. The American Heart Association[11] found that air pollution levels vary significantly in urban areas and that people who live close to highly congested roadways are exposed to greater health risks. The EPA also notes that NOx emissions are higher near busy roadways.

The bottom line is that—all things being equal—higher population density, more intense traffic congestion, and higher concentrations of air pollution go together.

All of this could have serious consequences as the EPA expands the strength of its misguided regulations. For example, officials in the Tampa–St. Petersburg area have expressed concern that the metropolitan area will not meet the new standards, and they have proposed densification as a solution, consistent with the misleading conventional wisdom. The reality is that this is likely to make things worse, not better. Officials there and elsewhere need to be aware of how densification worsens air pollution intensity and health risks and actually defeats efforts to meet federal standards.

Growth That Makes Areas Less Livable

There are myriad difficulties with smart growth and livability policies, including their association with higher housing prices, a higher cost of living, muted economic growth, and decreased mobility and access to jobs in metropolitan areas. As the EPA data show, the densification policies of smart growth and livability also make air pollution worse for people at risk, while increasing traffic congestion

Living close to the Freeway is not healthy for Children and other Living Things

The Sierra Club and the Environmental Law and Policy Center issue severe warnings about high density housing near freeways is unhealthy for people.

see WSJ Autism linked to environmental Factors

By SHIRLEY S. WANG

SAN SEBASTIÁN, Spain—Researchers at an international conference on autism Friday presented three new studies lending strength to the notion that environmental influences before birth play a role in the risk for the condition.In one study, pregnant women who were exposed to certain levels of air pollution were at increased risk of having a child with autism. Another presentation suggested that iron supplements before and early in pregnancy may lower the risk, and a third suggested some association between use of various household insecticides and a higher risk of autism.

Agence France Presse/Getty

Images

A new study finds that a pregnant woman's exposure to

certain levels of air pollution may contribute to an increased risk of autism in

her child. Here, an early morning photo shows poor air quality in Los

Angeles.

"The exciting thing about looking at environment, or environment and genes in conjunction with each other, is this provides the possibility of intervention," said Irva Hertz-Picciotto, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of California, Davis, who presented the study on insecticides.

Related Video

Speaking in a packed auditorium at the International Society for Autism Research annual conference here, Marc Weisskopf of the Harvard School of Public Health presented results from a large national study, known as the Nurses' Health Study II. The research suggested that a mother's exposure to high levels of certain types of air pollutants, such as metals and diesel particles, increased the risk of autism by an average of 30% to 50%, compared with women who were exposed to the lowest levels.

Dr. Weisskopf and his colleagues examined levels of some particles and pollutants that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has measured and studied across the country in the locations where the approximately 330 women from the study who reported having a child with autism lived. They compared the levels with 22,000 women who didn't have a child with autism, focusing on 14 pollutants that had been previously reported in the literature as possibly linked to autism.

The results mimicked those of previously published work on traffic pollution and autism risk in California. The consistency of findings across studies "certainly makes me start to feel much more certain that we're on a path to finding something environmental that's playing a role here," said Dr. Weisskopf, a professor of environmental health and epidemiology. "At this stage it does seem there's something related to air pollution."

Her team compared the mothers of 510 kids with an autism-spectrum disorder to mothers of 341 kids without autism. Mothers completed a phone survey that included questions on many types of environmental exposures, including supplements like prenatal vitamins, multivitamins and nutrient-specific vitamins, cereal and protein bars, which are often fortified with iron and other nutrients. They weren't asked about other dietary sources of iron, such as red meat and leafy green vegetables.

Dr. Schmidt cautioned that women shouldn't boost iron intake without getting their levels checked by a doctor, because too much iron can lead to toxicity. "It's much easier to change your diet or supplemental intake than it is to change your exposure to many other toxins," said Dr. Schmidt.

In a separate analysis of the Charge data, UC Davis researchers also found a relationship between exposure to some insecticides in the household, such as bug foggers, and features of autism, but more research is needed to understand why there is a potential link, said Dr. Hertz-Picciotto.

Write to Shirley S. Wang at shirley.wang@wsj.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)