Building 'Taj Mahals' with Taxpayer Money - Voice of San Diego: Pounding The Pavement

The 226 apartments at the downtown affordable housing high-rise Ten Fifty B cost an average of nearly $400,000 to build, most of which was funded by taxpayers. More than half of those apartments are 465-square-foot studios or 648-square-foot one-bedrooms.

Related Images

Related Stories

Related Links

The project has been a long time coming. The community waited for more than two decades while local government agencies put together one deal after another, only to watch those projects fall apart without a single hole being dug or nail being nailed.

The waiting list for the new apartments will grow to thousands of names, as families clamor for a chance to rent a sparkling new home at the edge of downtown for greatly reduced rates. Project boosters say it will breathe new life into a blighted area, increase tax revenues and entice private developers to invest in an overlooked neighborhood.

But along with the public benefit, the project also comes with a hefty price tag for taxpayers.

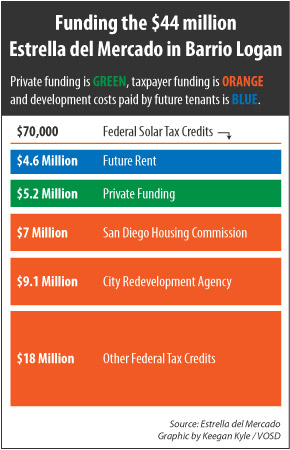

The $44 million apartment project will cost an average of $477,743 per unit, 90 percent of which will be paid by taxpayers. That’s twice what private developers say they’re spending to develop high-end apartments in the city today.

A few miles away, in Mission Valley, a private developer said he’s building top-shelf apartments for $225 a square foot. Another developer currently building upscale apartments downtown said his total cost is $275 a square foot.

The Estrella del Mercado apartments will cost $529 a square foot.

Taxpayers have poured almost $600 million into two dozen housing projects in the city of San Diego since 2007. A three-month voiceofsandiego.org investigation showed that, again and again, these projects are wildly more expensive than private developments.

Affordable housing is designed to provide homes for tens of thousands of working families who can’t afford to pay San Diego’s high rents. But with tens of millions of tax dollars set aside each year to build it, affordable housing in California has also evolved into a delivery mechanism for social goals that have little to do with that central mission — and even less to do with containing costs.

The result: Far fewer affordable apartments get built in San Diego than could be.

Today, many in the affordable housing industry describe their business simply as “The Game,” in which a core cadre of developers partner with government allies to build increasingly elaborate and expensive buildings in a lucrative, high-stakes competition funded by taxpayers.

“It’s just gotten out of hand,” said Tom Scott, former executive director of the San Diego Housing Federation, a coalition of affordable housing advocates and developers. “We need to re-evaluate where we’re headed with these public policy goals and recognize there’s a need to create as many units as we can, without just warehousing people.”

Far from the ugly concrete towers of the past, today’s affordable housing projects are often the best-designed, most beautiful buildings in their neighborhoods.

Click on the graphic above to view cost information

for all city affordable housing projects approved since

January 2007.

Developers and public agencies have been squeezed by increasingly restrictive regulations to construct buildings that aren’t just cheap to rent but also have exclusive features like solar panels, biodegradable carpets and free high-speed internet. They’ve been ordered to build in dense urban neighborhoods, where often the only scraps of land left are expensive-to-develop parcels already spurned by the private sector.

Add in the requirement to pay much higher wages than the market dictates, which can boost a project’s cost by as much as 25 percent, and the net effect of decades of government tinkering has been to add substantially to the cost of building affordable housing.

As local governments scrounge around for spare change to keep basic services like schools, libraries and public safety afloat, tens of millions of dollars remain locked down for the sole purpose of funding the affordable housing game.

That money could be spent doing what private developers are doing: Constructing different types of buildings that house perfectly nice high-end apartments and cost $200,000 to $275,000 per unit. But in San Diego it is often instead spent building what industry insiders derisively call “Taj Mahals” — beautiful places for a lucky few to live cheaply but that cost taxpayers dearly.

The Game

Photo by Sam Hodgson Jim Schmid, CEO of Chelsea Investment Corp., which is developing the Estrella del Mercado affordable apartments in Barrio Logan, says the cost of developing affordable housing in San Diego is out of control.

Affordable housing has been around in California for decades. Unlike private development, government-sponsored building has proven immune to the housing crisis, and some of the only apartments built in San Diego over the last few years have been affordable housing projects.

The concept has always been simple: Use government dollars to provide apartments to residents at subsidized rents.

City agencies lend private developers public money and help them get access to lucrative taxpayer-funded grants called tax credits. In exchange, the developers promise to limit rents in their buildings to levels dictated by the area’s median income.

The cheapest one-bedroom apartment in the Estrella del Mercado, for example, will rent for $460 a month, compared to a citywide average of $1,162, according tothe latest study by the San Diego County Apartment Association.

To qualify for that one-bedroom apartment, tenants must be able to prove they earn less than 30 percent of the area median income, which currently equals $17,310 a year for an individual or $24,720 for a family of four.

Every year, the state of California requires each county to build a certain amount of affordable housing. San Diego County divides that mandate among local cities and much of the burden falls on the city of San Diego.

Since January 2007, city agencies have subsidized the building of 2,134 apartments stretching from San Ysidro to Rancho Bernardo. That’s a drop in the bucket in a city with almost 240,000 rental properties, and where one local analyst estimates that 56 percent of renters, around 134,000 households, live in housing they can’t afford.

The cash for those projects came from a web of taxpayer-funded sources.

In some areas like downtown and southeastern San Diego, government redevelopment agencies have to spend 20 percent of the property taxes they receive to build affordable housing. Last year, city taxpayers paid $55 million into that fund. Developers in San Diego also have to build 10 percent of their homes affordable or pay into another city fund used to subsidize affordable housing.

Then there are tens of millions of dollars handed out each year in federal and state low-income tax credits. Those are given to developers who can prove their project’s worth to a powerful three-person committee made up of the state treasurer, controller and finance director.

The competitive process of convincing that Sacramento triumvirate to hand over tax credits is often cited as the chief culprit driving up the cost of building affordable housing in California today.

Developers spend months putting together applications that are often inches thick and that break down their projects to the finest detail. The trick is to score as high as possible on the committee’s points system, a process that during the last decade has become increasingly daunting and has resulted in escalating bills for taxpayers, who eventually foot the cost.

A Beauty Pageant

Photo by Sam Hodgson Residents of the affordable housing development Ten Fifty B enjoy such accoutrements as this fire pit, which overlooks the downtown skyline.

Developers know one thing when they head before the group known formally as the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee: The more cool features they can add to their project, the more likely it will win the competitive battle.

The winner-takes-all beauty pageant has become one of the major avenues for injecting public policy into affordable housing.

Build in urban areas near schools and transit, get points. Add in a community room, computers and evening classes on personal finance, get more points. Build green, bingo.

“The more you actually build — the more cost you take on on a project — the more competitive you’re gonna be,” said Robert Chavez, the city official overseeing the Mercado del Barrio project.

All those bells and whistles add cost to the project. But the final cost of building each apartment has become almost an afterthought in determining who gets tax credits.

While building more wins a developer points, there’s little incentive to build cheap, and the per-unit cost of a project is never considered in the committee’s points system.

The result: Price tags like $423,000 per unit for El Pedregal Family Apartments, a 45-unit project in San Ysidro, and $511,000 per unit for Cedar Gateway, currently under construction downtown. Both got perfect scores from the committee and both also got extra points because they secured additional loans from local public agencies, which kicked in millions to make the deals happen.

Jeanne Peterson, who now works as a Sacramento accountant, helped create the points system in the early 2000s. She said some criteria, such as building near schools and medical centers, sounded like good ideas at the time but have added so much cost they’ve backfired.

“There are brokers now that even advertise that their land meets the requirement for tax credits, so they charge much higher prices, which drives costs up,” said Peterson, who was the committee’s executive director from 1999 to 2004. “The system is not discouraging projects from having escalating costs.”

That hasn’t gone unnoticed by the committee. In an interview last month, Bill Pavão, the committee’s current executive director, who manages tax credits for State Treasurer Bill Lockyer, said the committee was assessing how to put cost front-and-center in its decision-making process.

“We’ve recognized that there’s a point when these prices have just spiraled out of control,” Pavão said.

Last week, the committee announced it will be holding a series of forums around the state to discuss how to contain costs on projects it funds. Projects receiving tax credits “generally may be more costly than necessary, fostering the public perception that affordable housing is too expensive,” read an announcement on the committee’s website.

Building Taj Mahals

Photo by Sam Hodgson The lobby of Ten Fifty B is adorned with curved, sculpted benches and boasts its green credentials along the walls.

The lobby of Ten Fifty B looks more like the entrance to a modern, upmarket hotel than the gateway to an affordable housing project.

Curved benches, sculpted from individually carved pieces of wood, sit under soft mood lighting. Along one wall, a glowing recycled panel flecked with inlaid pine needles and twigs lists the building’s sustainability achievements: gold LEED certification, rooftop solar panels, biodegradable carpeting and low-emission organic paints. Outside the front door, there’s a living wall inlaid with cacti and other plants.

It’s still tough sometimes for affordable housing boosters to convince neighborhoods to accept their projects. The buildings come with a stigma and community planning groups and neighbors often campaign hard against them.

So to ingratiate projects into unwelcoming neighborhoods, developers often conceive buildings that are architecturally and aesthetically superior to anything else on the block.

Building stunning real estate serves another stated purpose of the agencies tasked with creating affordable housing: eliminating blight in run-down neighborhoods that have been designated as redevelopment areas.

But building beautiful doesn’t come cheap. By the time it opened last year, each of the 226 apartments at Ten Fifty B had cost taxpayers almost $400,000. More than half of those apartments are 465-square-foot studios or 648-square-foot one-bedrooms.

Kent Robertson, a Santa Ana consultant, has surveyed hundreds of private and public projects as a cost evaluator for lenders, investors and developers. He said affordable housing projects almost always have expensive architectural features for “100 percent aesthetic reasons.”

“The architect is just let go,” Robertson said. “He’s creating a resume-boosting building.”

Affordable housing developers pointed out that building sustainable, durable buildings saves money in the long run, however.

Jim Silverwood, president of Affirmed Housing Group, which developed Ten Fifty B, said including all the cutting-edge sustainability elements into his building cost less than 1 percent of the total construction price. The energy cost savings over the life of the project will pay for that many times over, he said.

And buildings like Ten Fifty B are built durable because they’re government investments designed to last at least the 65 years they’ll remain affordable, Silverwood said.

A Bigger Paycheck, a Higher Cost

Photo by Sam Hodgson Workers at the Mercado del Barrio construction site make a government-mandated “prevailing wage,” which drives up project costs by as much as 25 percent.

For the average construction worker in San Diego, an affordable housing project represents more than a stable job for a few weeks or months. It also means a significantly fatter paycheck.

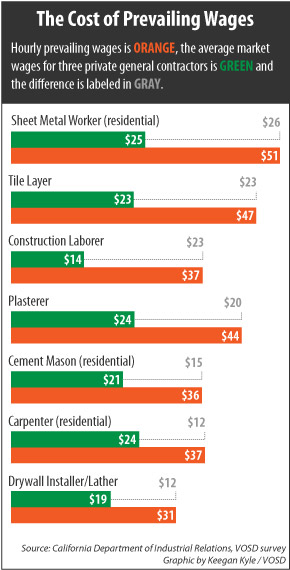

Contractors on most government projects are required to pay their workers “prevailing wages,” which in California are set by the Department of Industrial Relations and typically reflect wage levels set by labor unions. On San Diego construction sites, where many workers are not unionized, the requirement to pay prevailing wages can make a big difference both to workers and to project costs.

Unskilled workers on the Mercado del Barrio project construction site, for example, will be paid between $35 and $44 an hour for performing basic tasks like sweeping and digging holes. That’s equivalent to $72,000 to $92,000 a year.

A survey of three local general contractors who do private development showed they pay unskilled workers or laborers more like $14 an hour.

Four affordable housing developers said prevailing wages push development costs up by 20 to 25 percent. Jim Schmid, CEO of Chelsea Investment Corp., which is developing the Estrella del Mercado, said that means 20 to 25 percent fewer affordable apartments get built.

“We have many projects with a thousand people on the waiting list,” he said. “If the units cost less we could build more of them and more San Diegans could live in an affordable home.”

But supporters of prevailing wages said paying workers at the lower end of the spectrum would create a paradox: Building more affordable housing while at the same time creating more people who need government-subsidized apartments.

Prevailing wages help give unskilled laborers a financial boost so they can rise into the middle class, said Susan Tinsky, current executive director of the San Diego Housing Federation.

“We should have a holistic approach and we shouldn’t be perpetuating public policy problems when we spend our public dollars,” she said.

‘Just Absurd’

Photo by Sam Hodgson The City Council approved construction of 24 apartment units on El Cajon Boulevard in October 2007. The North Park project, known as the Boulevard Apartments, was budgeted to cost $11.6 million, or $506,609 per unit.

In a private real estate development deal, the profit comes in a tangible form: Dollars and cents.

Private developers decide what and where to build by surveying the market and seeing what makes sense financially — what’s going to make them the most money. That means weighing the future income they can make from a project against all the cost that go into developing it.

In pure economic terms, today’s affordable housing projects don’t fare well in that equation.

“It’s just absurd to pay $400,000 for a studio. You could be buying every family a 5,000 square-foot house in Eastlake for that,” said Steve Huffman, a real estate broker who regularly sells local apartment buildings.

But in the affordable housing game, profits are a more amorphous beast. The value an affordable apartment building will bring to the community comes in hard-to-measure forms like the elimination of a blighted block or, in a mixed use project like the Mercado del Barrio, the creation of a development meant to give a neighborhood a vibrant nucleus.

These benefits of planned affordable housing projects are discussed at length in community meetings, committees, staff meetings and, eventually, in a public meeting of the San Diego City Council, the ultimate arbiter for deciding which projects get city funding.

But the other side of the equation, how much the projects actually end up costing the taxpayer, is almost never talked about.

A stark example is the Boulevard Apartments in North Park, a 24-unit project that looks out across El Cajon Boulevard’s smoke shops and check-cashing centers.

The building, which opened in 2009, is extraordinary in local affordable housing for another reason than its total development budget of $485,500 an apartment: Somebody at a local public agency criticized the project’s high per-unit cost in the run-up to its approval.

In hundreds of pages of reports, analyses and financial documents on the projects examined for this story, concern over a project’s high per-unit cost appeared just once: A city Redevelopment Agency report prepared for a City Council meeting to discuss the project, says its loan committee recommended not approving the subsidy “due to the concern that the total cost per unit appears high in comparison to other projects.”

That one sentence, in a report that otherwise waxes lyrical about the project, never made it into the final discussion of the Boulevard Apartments, which took place at the Oct. 30, 2007 City Council meeting.

Then-Council President Scott Peters introduced the item.

“Can you give us three or four sentences on why it’s so great?” Peters asked then-Councilwoman Toni Atkins, in whose district the apartments were to be built.

Atkins then did just that. Just more than a minute later, the $11.6 million project was approved unanimously.

The whole discussion, from introduction to final vote, lasted about 90 seconds.

Correction: This story originally stated that the budgeted per-unit cost of the Boulevard Apartments was $506,609. That figure neglected to take into account the manager’s apartment, which was not designated affordable. When that unit is factored in, the per-unit cost is actually $485,500. We’ve also updated it to include 983 square feet of internal common area for the Estrella del Mercado, which we did for other projects, and to reflect a slightly larger rentable square footage area for the building based on more recent plans. That changed the square-foot development cost from $542 to $529.We regret the errors.

Please contact Will Carless directly at will.carless@voiceofsandiego.org or at 619.550.5670 and follow him on Twitter: twitter.com/willcarless.

Voice of San Diego is a nonprofit that depends on you, our readers. Please donate to keep the service strong. Click here to find out more about our supporters and how we operate independently.

Value investigative reporting? Support it. Donate Now.

The project has been a long time coming. The community waited for more than two decades while local government agencies put together one deal after another, only to watch those projects fall apart without a single hole being dug or nail being nailed.

The waiting list for the new apartments will grow to thousands of names, as families clamor for a chance to rent a sparkling new home at the edge of downtown for greatly reduced rates. Project boosters say it will breathe new life into a blighted area, increase tax revenues and entice private developers to invest in an overlooked neighborhood.

But along with the public benefit, the project also comes with a hefty price tag for taxpayers.

The $44 million apartment project will cost an average of $477,743 per unit, 90 percent of which will be paid by taxpayers. That’s twice what private developers say they’re spending to develop high-end apartments in the city today.

A few miles away, in Mission Valley, a private developer said he’s building top-shelf apartments for $225 a square foot. Another developer currently building upscale apartments downtown said his total cost is $275 a square foot.

The Estrella del Mercado apartments will cost $529 a square foot.

Taxpayers have poured almost $600 million into two dozen housing projects in the city of San Diego since 2007. A three-month voiceofsandiego.org investigation showed that, again and again, these projects are wildly more expensive than private developments.

Affordable housing is designed to provide homes for tens of thousands of working families who can’t afford to pay San Diego’s high rents. But with tens of millions of tax dollars set aside each year to build it, affordable housing in California has also evolved into a delivery mechanism for social goals that have little to do with that central mission — and even less to do with containing costs.

The result: Far fewer affordable apartments get built in San Diego than could be.

Today, many in the affordable housing industry describe their business simply as “The Game,” in which a core cadre of developers partner with government allies to build increasingly elaborate and expensive buildings in a lucrative, high-stakes competition funded by taxpayers.

“It’s just gotten out of hand,” said Tom Scott, former executive director of the San Diego Housing Federation, a coalition of affordable housing advocates and developers. “We need to re-evaluate where we’re headed with these public policy goals and recognize there’s a need to create as many units as we can, without just warehousing people.”

Far from the ugly concrete towers of the past, today’s affordable housing projects are often the best-designed, most beautiful buildings in their neighborhoods.

|

| Click on the graphic above to view cost information for all city affordable housing projects approved since January 2007. |

Developers and public agencies have been squeezed by increasingly restrictive regulations to construct buildings that aren’t just cheap to rent but also have exclusive features like solar panels, biodegradable carpets and free high-speed internet. They’ve been ordered to build in dense urban neighborhoods, where often the only scraps of land left are expensive-to-develop parcels already spurned by the private sector.

Add in the requirement to pay much higher wages than the market dictates, which can boost a project’s cost by as much as 25 percent, and the net effect of decades of government tinkering has been to add substantially to the cost of building affordable housing.

As local governments scrounge around for spare change to keep basic services like schools, libraries and public safety afloat, tens of millions of dollars remain locked down for the sole purpose of funding the affordable housing game.

That money could be spent doing what private developers are doing: Constructing different types of buildings that house perfectly nice high-end apartments and cost $200,000 to $275,000 per unit. But in San Diego it is often instead spent building what industry insiders derisively call “Taj Mahals” — beautiful places for a lucky few to live cheaply but that cost taxpayers dearly.

The Game

Affordable housing has been around in California for decades. Unlike private development, government-sponsored building has proven immune to the housing crisis, and some of the only apartments built in San Diego over the last few years have been affordable housing projects.

The concept has always been simple: Use government dollars to provide apartments to residents at subsidized rents.

City agencies lend private developers public money and help them get access to lucrative taxpayer-funded grants called tax credits. In exchange, the developers promise to limit rents in their buildings to levels dictated by the area’s median income.

The cheapest one-bedroom apartment in the Estrella del Mercado, for example, will rent for $460 a month, compared to a citywide average of $1,162, according tothe latest study by the San Diego County Apartment Association.

To qualify for that one-bedroom apartment, tenants must be able to prove they earn less than 30 percent of the area median income, which currently equals $17,310 a year for an individual or $24,720 for a family of four.

Every year, the state of California requires each county to build a certain amount of affordable housing. San Diego County divides that mandate among local cities and much of the burden falls on the city of San Diego.

Since January 2007, city agencies have subsidized the building of 2,134 apartments stretching from San Ysidro to Rancho Bernardo. That’s a drop in the bucket in a city with almost 240,000 rental properties, and where one local analyst estimates that 56 percent of renters, around 134,000 households, live in housing they can’t afford.

The cash for those projects came from a web of taxpayer-funded sources.

In some areas like downtown and southeastern San Diego, government redevelopment agencies have to spend 20 percent of the property taxes they receive to build affordable housing. Last year, city taxpayers paid $55 million into that fund. Developers in San Diego also have to build 10 percent of their homes affordable or pay into another city fund used to subsidize affordable housing.

Then there are tens of millions of dollars handed out each year in federal and state low-income tax credits. Those are given to developers who can prove their project’s worth to a powerful three-person committee made up of the state treasurer, controller and finance director.

The competitive process of convincing that Sacramento triumvirate to hand over tax credits is often cited as the chief culprit driving up the cost of building affordable housing in California today.

Developers spend months putting together applications that are often inches thick and that break down their projects to the finest detail. The trick is to score as high as possible on the committee’s points system, a process that during the last decade has become increasingly daunting and has resulted in escalating bills for taxpayers, who eventually foot the cost.

A Beauty Pageant

Developers know one thing when they head before the group known formally as the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee: The more cool features they can add to their project, the more likely it will win the competitive battle.

The winner-takes-all beauty pageant has become one of the major avenues for injecting public policy into affordable housing.

Build in urban areas near schools and transit, get points. Add in a community room, computers and evening classes on personal finance, get more points. Build green, bingo.

“The more you actually build — the more cost you take on on a project — the more competitive you’re gonna be,” said Robert Chavez, the city official overseeing the Mercado del Barrio project.

All those bells and whistles add cost to the project. But the final cost of building each apartment has become almost an afterthought in determining who gets tax credits.

While building more wins a developer points, there’s little incentive to build cheap, and the per-unit cost of a project is never considered in the committee’s points system.

The result: Price tags like $423,000 per unit for El Pedregal Family Apartments, a 45-unit project in San Ysidro, and $511,000 per unit for Cedar Gateway, currently under construction downtown. Both got perfect scores from the committee and both also got extra points because they secured additional loans from local public agencies, which kicked in millions to make the deals happen.

Jeanne Peterson, who now works as a Sacramento accountant, helped create the points system in the early 2000s. She said some criteria, such as building near schools and medical centers, sounded like good ideas at the time but have added so much cost they’ve backfired.

“There are brokers now that even advertise that their land meets the requirement for tax credits, so they charge much higher prices, which drives costs up,” said Peterson, who was the committee’s executive director from 1999 to 2004. “The system is not discouraging projects from having escalating costs.”

That hasn’t gone unnoticed by the committee. In an interview last month, Bill Pavão, the committee’s current executive director, who manages tax credits for State Treasurer Bill Lockyer, said the committee was assessing how to put cost front-and-center in its decision-making process.

“We’ve recognized that there’s a point when these prices have just spiraled out of control,” Pavão said.

Last week, the committee announced it will be holding a series of forums around the state to discuss how to contain costs on projects it funds. Projects receiving tax credits “generally may be more costly than necessary, fostering the public perception that affordable housing is too expensive,” read an announcement on the committee’s website.

Building Taj Mahals

|

No comments:

Post a Comment