The voters who put Barack Obama in office expected some big changes. From the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping to Guantanamo Bay to the Patriot Act, candidate Obama was a defender of civil liberties and privacy, promising a dramatically different approach from his predecessor.

But six years into his administration, the Obama version of national security looks almost indistinguishable from the one he inherited. Guantanamo Bay remains open. The NSA has, if anything, become more aggressive in monitoring Americans. Drone strikes have escalated. Most recently it was reported that the same president who won a Nobel Prize in part for promoting nuclear disarmament is spending up to $1 trillion modernizing and revitalizing America’s nuclear weapons.

Why did the face in the Oval Office change but the policies remain the same? Critics tend to focus on Obama himself, a leader who perhaps has shifted with politics to take a harder line. But Tufts University political scientist Michael J. Glennon has a more pessimistic answer: Obama couldn’t have changed policies much even if he tried.

Though it’s a bedrock American principle that citizens can steer their own government by electing new officials, Glennon suggests that in practice, much of our government no longer works that way. In a new book, “National Security and Double Government,” he catalogs the ways that the defense and national security apparatus is effectively self-governing, with virtually no accountability, transparency, or checks and balances of any kind. He uses the term “double government”: There’s the one we elect, and then there’s the one behind it, steering huge swaths of policy almost unchecked. Elected officials end up serving as mere cover for the real decisions made by the bureaucracy.

Glennon cites the example of Obama and his team being shocked and angry to discover upon taking office that the military gave them only two options for the war in Afghanistan: The United States could add more troops, or the United States could add a lot more troops. Hemmed in, Obama added 30,000 more troops.

Glennon’s critique sounds like an outsider’s take, even a radical one. In fact, he is the quintessential insider: He was legal counsel to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a consultant to various congressional committees, as well as to the State Department. “National Security and Double Government” comes favorably blurbed by former members of the Defense Department, State Department, White House, and even the CIA. And he’s not a conspiracy theorist: Rather, he sees the problem as one of “smart, hard-working, public-spirited people acting in good faith who are responding to systemic incentives”—without any meaningful oversight to rein them in.

How exactly has double government taken hold? And what can be done about it? Glennon spoke with Ideas from his office at Tufts’ Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. This interview has been condensed and edited.

IDEAS: Where does the term “double government” come from?

GLENNON:It comes from Walter Bagehot’s famous theory, unveiled in the 1860s. Bagehot was the scholar who presided over the birth of the Economist magazine—they still have a column named after him. Bagehot tried to explain in his book “The English Constitution” how the British government worked. He suggested that there are two sets of institutions. There are the “dignified institutions,” the monarchy and the House of Lords, which people erroneously believed ran the government. But he suggested that there was in reality a second set of institutions, which he referred to as the “efficient institutions,” that actually set governmental policy. And those were the House of Commons, the prime minister, and the British cabinet.

IDEAS: What evidence exists for saying America has a double government?

GLENNON:I was curious why a president such as Barack Obama would embrace the very same national security and counterterrorism policies that he campaigned eloquently against. Why would that president continue those same policies in case after case after case? I initially wrote it based on my own experience and personal knowledge and conversations with dozens of individuals in the military, law enforcement, and intelligence agencies of our government, as well as, of course, officeholders on Capitol Hill and in the courts. And the documented evidence in the book is substantial—there are 800 footnotes in the book.

IDEAS: Why would policy makers hand over the national-security keys to unelected officials?

GLENNON: It hasn’t been a conscious decision....Members of Congress are generalists and need to defer to experts within the national security realm, as elsewhere. They are particularly concerned about being caught out on a limb having made a wrong judgment about national security and tend, therefore, to defer to experts, who tend to exaggerate threats. The courts similarly tend to defer to the expertise of the network that defines national security policy.

The presidency itself is not a top-down institution, as many people in the public believe, headed by a president who gives orders and causes the bureaucracy to click its heels and salute. National security policy actually bubbles up from within the bureaucracy. Many of the more controversial policies, from the mining of Nicaragua’s harbors to the NSA surveillance program, originated within the bureaucracy. John Kerry was not exaggerating when he said that some of those programs are “on autopilot.”

IDEAS: Isn’t this just another way of saying that big bureaucracies are difficult to change?

GLENNON: It’s much more serious than that. These particular bureaucracies don’t set truck widths or determine railroad freight rates. They make nerve-center security decisions that in a democracy can be irreversible, that can close down the marketplace of ideas, and can result in some very dire consequences.

IDEAS: Couldn’t Obama’s national-security decisions just result from the difference in vantage point between being a campaigner and being the commander-in-chief, responsible for 320 million lives?

GLENNON: There is an element of what you described. There is not only one explanation or one cause for the amazing continuity of American national security policy. But obviously there is something else going on when policy after policy after policy all continue virtually the same way that they were in the George W. Bush administration.

IDEAS: This isn’t how we’re taught to think of the American political system.

GLENNON: I think the American people are deluded, as Bagehot explained about the British population, that the institutions that provide the public face actually set American national security policy. They believe that when they vote for a president or member of Congress or succeed in bringing a case before the courts, that policy is going to change. Now, there are many counter-examples in which these branches do affect policy, as Bagehot predicted there would be. But the larger picture is still true—policy by and large in the national security realm is made by the concealed institutions.

IDEAS: Do we have any hope of fixing the problem?

GLENNON: The ultimate problem is the pervasive political ignorance on the part of the American people. And indifference to the threat that is emerging from these concealed institutions. That is where the energy for reform has to come from: the American people. Not from government. Government is very much the problem here. The people have to take the bull by the horns. And that’s a very difficult thing to do, because the ignorance is in many ways rational. There is very little profit to be had in learning about, and being active about, problems that you can’t affect, policies that you can’t change.

If you are a tech worker, it probably wouldn’t be very logical to vote for Campos. He has sided against tech on the key votes of the last several years

If you are a tech worker, it probably wouldn’t be very logical to vote for Campos. He has sided against tech on the key votes of the last several years  Chiu has positioned himself as someone who has the wherewithal to get difficult legislation passed and staked a lot on this very politically risky effort to legalize and regulate short-term stays. Indeed, regulating Airbnb is a total rat’s nest in a city that has a long history of incredibly contentious land-use debates. Chiu’s legislation

Chiu has positioned himself as someone who has the wherewithal to get difficult legislation passed and staked a lot on this very politically risky effort to legalize and regulate short-term stays. Indeed, regulating Airbnb is a total rat’s nest in a city that has a long history of incredibly contentious land-use debates. Chiu’s legislation

Another candidate that’s received widespread support across the political spectrum is Nicholas Josefowitz, who is running for one of the two BART board seats representing San Francisco.

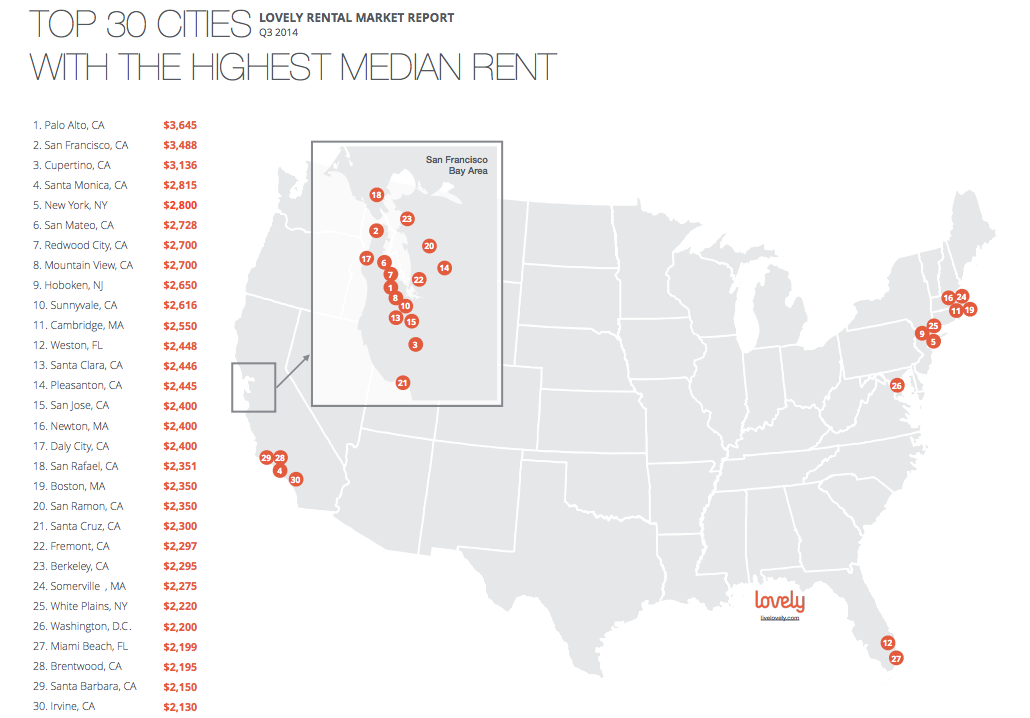

Another candidate that’s received widespread support across the political spectrum is Nicholas Josefowitz, who is running for one of the two BART board seats representing San Francisco. Oakland is the major spillover community for people who are displaced or priced out of San Francisco and

Oakland is the major spillover community for people who are displaced or priced out of San Francisco and