The NIMBY Principle

LAURA BLISS JUL 26, 2019

The advocacy group Livable California has led the resistance to the state’s biggest housing proposals. What's their appeal for “local control” really about?

Susan Kirsch’s backyard is, predictably, beautiful. Past the sunny wooden patio, tomatoes, blueberries, and poppies blossom between rugged pathways. A birdbath draws sparrows to the center; a lemon tree drapes over the back fence.

But all is not perfect. Next door, her neighbors recently added a detached room, which peeks over the side fence and cuts off part of Kirsch’s view of Marin County’s rolling hills.

“It broke my heart,” she told me. “But at least it was only one story.”

In California, the debate between NIMBYs and YIMBYs—that’s Not In My Backyard and Yes In My Backyard, respectively—doesn’t usually involve actual backyards. It’s about housing: By one estimate, the state is short 3.5 million homes to accommodate current and projected demand. In cities like San Francisco, this gap has raised rents to some of the highest in the nation, fueling a homelessness problem that the United Nations recently labeled a human rights violation.

The scale of this problem has fractured the voters of this largely progressive region, pushing Californians of varying political stripes into rival camps that don’t neatly subdivide along the usual left-right lines. Struggles between homeowners and newcomers over development are fixtures of neighborhood-level politics nationwide, but the Bay Area’s version of this narrative might be the most bitterly contested in the U.S., fueled by a uniquely Californian cocktail of economic and cultural factors.

This particular backyard holds some clues about why that is, and in particular, what motivates a certain powerful segment of older, relatively liberal, home-owning Californians. Among urbanists who promote density-boosting zoning reforms, “NIMBY” is usually a pejorative. While Kirsch doesn’t appreciate the negative connotations, to her, the term can imply something good.

“It’s about people being stewards of what they love and care about,” she told me over coffee at her home in Mill Valley, an enclave north of San Francisco surrounded by natural preserves. “It’s care-giving, not excluding care for others.”

In early 2018, at age 74, Kirsch founded Livable California, a nonprofit that advocates for slow growth and local control over urban development issues. With Kirsch at the helm, the group has rallied suburbanites around the state against two high-profile housing bills that proposed to open up some communities to denser development. Their opposition helped kill both: The first bill, SB 827, was quickly defeated in committee; the second one, SB 50, was shelved until 2020.

The rhetoric around the bills has been heated. Residents who oppose the zoning changes (which would, by and large, allow just a few extra stories of residential development) have been made out as a bunch of narrowly self-interested geriatrics, unconcerned with the economic plight of younger adults. “It has begun to feel like the politics of an older generation saying, ‘Fuck you, I got mine,’” Henry Grabar wrote in Slate in May. Meanwhile, at least in the Bay Area, where the YIMBY movement took root, pro-housing activists are often made out by their foes as self-entitled Millennials whose political leaders are bankrolled by the real estate industry. “That was their message: ‘I don’t care about preservation or you people with those old Victorians. It’s our time now and you should die. You are in the way,’” is how one San Francisco preservationist summed up the YIMBY sentimentfrom a recent community meeting.

Cities are changing fast. Keep up with the CityLab Daily newsletter.The best way to follow issues you care about.Subscribe

Loading...

But this narrative of class and generational combat is incomplete. Lower-income renters and homeowners are in this conversation, too, and their allegiance is somewhat torn. Some tenants rights groups buy the logic that an increased housing supply would benefit them, but at least as many view the prospect of high-volume, market-rate housing as a threat to already gentrifying neighborhoods.

Indeed, the NIMBY-YIMBY binary often reduces each sides’ arguments to cartoons, with neither camp spending much effort to understand the hopes and fears of their adversaries. Both factions are intensely community-minded and profess to love their cities and neighborhoods. Yet each seems convinced that the other represents an attack on their respective futures.

Is there any way to try to bridge this divide and find some common ground? One approach might be look deeper into the ostensible NIMBY instinct—to see if the forces that drive these passionate defenders of the neighborhood status quo are richer than pure self-interest and fear of outsiders.

It turns out, yes, they are. But also, there’s some of that stuff, too.

***

Wendy Sarkissian, a Life Fellow at the Planning Institute of Australia, has worked as a social planning consultant and academic since 1969. The co-author of the book Housing As If People Mattered, Sarkissian has theorized extensively on the psychology of NIMBYism, which is related to what academics term as “place attachment.” People latch onto their surrounding environments for psychological refuge and safety, and perceived threats can summon an instinct towards defense, she told me: “We are nothing if we’re not animals, after all. We seem to be hardwired for this.”

But emotions are hard to talk about, and to guard beloved homes and communities from change that’s outside our control, we often adopt complex rationales, Sarkissian notes. Neighborhood skirmishes over a new grocery store’s traffic impacts, or concerns about surface runoff, can elide deeply felt connections to a place.

Glenn Albrecht, the Australian philosopher who coined the term “solastalgia”—the psychological pain created by environmental destruction—agrees. “I’m at the point where I think these little battles are genuine expressions of people trying to maintain their connections to life and things,” he told me.

Long before launching Livable California, Kirsch proved an effective channeler of the pro-suburban animus. SB 375, a landmark piece of California legislation from 2008 that asked regional authorities to set emissions reductions goals and plan for transit and housing that requires less car travel, marked the start of much of her activism. She may drive a Prius and support the Sierra Club, but a future where people are smushed into denser neighborhoods and deprived of personal vehicles sounds to Kirsch like the stuff of a developing nation. “That’s a really horrifying thought to me: that most peoples’ greatest asset would be a bicycle,” she said. “That’s a diminishment of the American dream.”

And she objects to the way California’s climate policies have reemerged at the local level. In 2007, Kirsch organized neighbors to kill plans for a mixed-use housing development on a major commercial thoroughfare in Mill Valley. Then she co-founded a slow-growth advocacy group for her town, and later the countywide Citizen Marin, which battled more high-density projects and regional urban plans. In 2016, Kirsch attempted to unseat a Marin County commissioner, running on a platform of slow growth, fiscal restraint, and keeping Marin politics tightly focused on Marin. “Climate change is a serious problem, and we need to get a handle on it,” she said in her announcement for candidacy. “But we need to get a handle by focusing on local control: local solutions for local issues.” She lost the race, but with a respectable 42 percent of the vote.

Kirsch’s own home is modest. It’s a World War II-era, single-story three-bedroom bungalow with a snug kitchen and a living room large enough for a couch, a coffee table, and not a whole lot more. She raised her two children here; now divorced, she lives alone, save for the Airbnb guests who sometimes book a guest suite. Her Mill Valley street is full of these little houses, each now worth around $1.5 million.

Kirsch grew up on a farm in Minnesota, earned degrees in English and speech communication, and worked as an educator in Cleveland and Oregon before landing in Marin County 40 years ago. Long known as a bastion of 1960s-style communitarianism, the county is 80 percent undeveloped; its forested hills and craggy shoreline are largely intact thanks to a century of determined conservationism. Limits on developable land, strict local zoning laws, and the growth of the city across the Golden Gate Bridge has meant that housing demand has long outstripped supply.

In early 2018, momentum in the California senate was building behind SB 827, a bill authored by Senator Scott Wiener that would “upzone” certain neighborhoods. If they were near frequent transit service, parcels reserved for single-family homes would be unlocked for higher-density development. To Kirsch, the bill felt like yet another dictum from state authorities telling her community how to behave. Meanwhile, in San Francisco, the streets were full of homeless people, and her county was barely taking care of its existing public housing. More market-rate apartments weren’t going to solve their problems. And with a central shopping crossroads just around the corner, her own home was in upzone territory.

After meeting up at a greasy spoon in San Francisco to discuss strategies, Kirsch and a group of friends from around the Bay Area launched a movement that quickly went statewide.

Over the next year, Livable California rallied residents to testify in Sacramento, write letters to their representatives, and spread the word against the bill through maps and images that showed leafy suburban blocks overshadowed by high-rise apartments and crowded with parked cars. Kirsch penned a raft of op-eds in her own local paper, as she has been doing for years. “We voted for local representatives to thoughtfully plan a community that reflects our values,” she wrote in the Marin Journal. “A one-size-fits-all mandate violates democratic principles, forcing us to pay for unregulated private development in the service of billion-dollar corporations.”

After SB 827 died in its first committee hearing, in large part because it didn’t go far enough to protect gentrifying neighborhoods, Wiener revised it and put forth SB 50 in 2019. In some respects, this bill targeted affluent neighborhoods even more narrowly by proposing to upzone “jobs-rich” areas, too; even if they were far from regular transit service, single-family parcels close to big employment centers would be eligible for an extra story or two, too. Livable California campaigned harder, showing up to lobby in Sacramento, speaking out at community meetings in Palo Alto, Orinda, Cupertino, and San Carlo, and protesting Wiener’s public appearances. It joined forces with a like-minded group in Southern California called the Coalition to Preserve L.A., which released a video called “Will SB 50 Kill Your Neighborhood?,” claiming that luxury condos were going to raze entire blocks. Critically, the group connected suburban homeowners from San Diego to Marin with mayors and city council members, who in turn voiced their own dissent.California’s YIMBYs now find themselves is a difficult position: They’ve whacked a hornet’s nest full of some of the nation’s most powerful voters.

It’s hard to escape the fact that most of the communities that glommed onto Livable California represent older, whiter, and more affluent homeowners from some of the most desirable enclaves in California. That is a perception that the group itself is aware of: In an internal email that was recently picked up and tweeted by a Wiener staffer, one Livable California member wrote that “housing activists ... are deeply suspicious of ‘white suburban NIMBYs’ and the objectives of Livable California.”

Kirsch recognizes these less-than-ideal optics, as well as the link between old, racist redlining practices and contemporary zoning codes. But she insists that Livable California’s only interest is keeping neighborhoods intact. As proof, she points to the pro-tenant groupsthat have aligned with the group to defeat SB 50 and its kin, out of fears of gentrification and displacement. And she talks about “activating” her fellow retirees, awakening them to what they can still achieve for the greater good. “I’m really more in favor of advancing, or whatever the opposite is of retiring,” Kirsch said.

Critics might object to this framing, but California’s suburban defenders can indeed be said to be fueled by a kind of altruism, at least for one another and for future residents who share their values. Indeed, the upzoning bills show that Livable California’s resistance is not entirely about protecting narrow economic interests: Kirsch and her neighbors would make great money selling their lots to a developer looking to build a few midrises.

But they’re not. Established residents often see themselves as long-term shareholders in their community, said Clayton Nall, a political scientist at Stanford who has studied grassroots community organizing. As such, they feel a responsibility for protecting the community against perceived threats, which might include pollution, crime, and the undesirable effects of over-development. Indeed, back in the 1960s and ’70s, NIMBYs were the people fighting highways and oil refineries in their backyards, not fourplexes. In battling upzoning, some NIMBYs are animated by the fear of a takeover of their neighborhoods by commercial interests.

“The possibility that their property interests will then be defined by corporate actors like landlords is frightening to them,” Nall said. “And it complicates their effort to protect their common interest as homeowners defending a shared way of living in their particular neighborhoods.” In other words, the distant landlords of a multi-unit building may not see the local value, of, say, tending lovely front-yard gardens.

The greed of developers and the overreach of government actors certainly come up a lot with Kirsch; to her, both seem to be strong-arming communities into cookie-cutter, “smart growth” developments. Kirsch ties these forces to the decline of homeownership since the 2008 economic crash, and the banks and investors that took over many of those foreclosures. With fewer properties in individual hands, ”the strength of a voting public is further and further diminished,” she said. Meanwhile, in the Bay Area, the tech companies whose massive success has fueled demand for housing aren’t fairly redistributing their profits. The real California housing crisis, she believes, is the runaway growth of that industry, not this handful of older homeowners trying to save their bungalow neighborhoods.

This last element of Kirsch’s thinking finds some enthusiastic and perhaps unlikely cosponsors. Richard Walker, the David Harvey-trained Marxist geographer, professor emeritus of economic geography at UC Berkeley, and longtime observer of the dark side of the Bay Area’s tech boom, says that California’s YIMBYs get the economics of the housing crisis wrong by focusing myopically on the “supply” side of the equation. When demand for housing is driven solely by the most affluent renters and buyers in a marketplace, home prices and rents are bound to run away to astronomical heights, Walker explains; this is exactly what has happened as Apple, Google, and Facebook have gotten away with paying so little in taxes and employing vast numbers of well-paid employees. “That’s who the developers want to accommodate, and it leaves working people out of the equation,” he said.

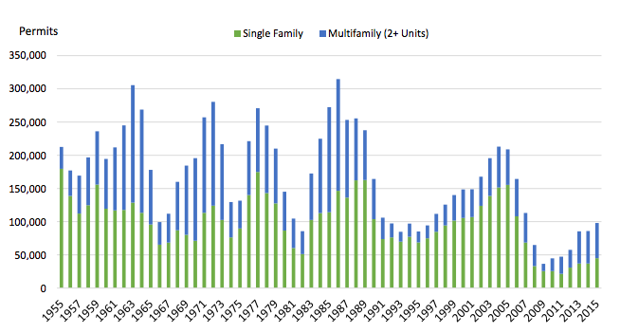

Walker is skeptical that giving developers more room to play is likely to fix the housing crisis. Instead, taxing and regulating the tech industry so that more of its profits would find their way into the pockets of the working class would go a lot further, he thinks. Restrengthening unions to set wages higher and put more housing within reach is another solution. “When was the last time a massive amount of working-class housing was built?” Walker asked. “Post-World War II, because it was the most equal time since before the Civil War.”

There are definitely progressive leaders making variations on this argument; Senator Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign platform emphasizes raising taxes on the most affluent, regulating tech, and bolstering organized labor. But with the NIMBY-vs.-YIMBY dynamic overshadowing everything else in housing politics, a mess of ideas and principles are getting glopped into two seemingly opposed buckets. The Trump White House also wants zoning reform, of some sort, which makes liberal-leaning YIMBYs pretty uncomfortable. Meanwhile, conservatives and Marxists ally themselves against legislation like SB 50. Something about the logic of upzoning must be murky if so many divergent thinkers can interpret it as a win or loss.

***

One big problem with SB 50, Nall believes, is that its beneficiaries aren’t clear, other than the real estate developers who back it, and, perhaps, the young white-collar renters who might easily afford to move to Austin instead. Housing isn’t a pure supply-and-demand problem; location is a huge factor. Some say that the amount of demand to live in the Bay is literally insatiable, and that costs will never come down naturally. And the jury is out on whether “trickle-down housing”—also known as filtering—brings down rents. You could fill a basketball court with the economists and policy wonks who are arguing about this right now.

This is not to say that upzoning isn’t called for, along with (say) tenant protection laws and funds for low-income housing. It’s gaining traction nationally as one tool that can close housing gaps: Minneapolis has a new plan to allow for denser development citywide, and Oregon passed a bill that allows duplexes and triplexes to replace detached houses in urban areas across the state. The champions of these plans were successful, in part because they found ways to unite communities around shared values that went beyond attachments to their own blocks. Oregon’s bill is built on the state’s long history of conservation-minded urban growth management; in Minneapolis, upzoning proponents highlighted the racist origins of zoning codes and the importance of working to erase them.

In contrast, it seems California’s upzoning advocates have struggled to show how such unlocking more market-rate (read: expensive) apartments in suburban neighborhoods would help those with the biggest housing challenges. While Kirsch applauds their commitment to civic engagement, YIMBYs also strike her as whiny. “Few of us have had housing just handed to us at the level that we might havewanted,” Kirsch told me. (She compares them to her CEO daughter, who bought a house in Oakland, with financial help from mom.) California’s YIMBYs now find themselves in a difficult position: They’ve whacked a hornet’s nest full of some of the nation’s most powerful voters.

Bu the zoning reformers have succeeded in introducing a big, bold idea for addressing a crisis that demands all kinds of different solutions. Livable California, on the other hand, is short on fixes. Part of its stated mission is to “empower communities to take action to support local community planning and decision-making with the goal of an equitable and sustainable future for California.” Yet its website offers no examples of how else to accommodate Californians who would also like to live, “livably.” Instead, it’s full of links to articles and materials opposing various state housing bills.

One could not be blamed for noticing that such politics serve to protect the single-family status quo. And this is where the NIMBY principle draws its clearest line: Fundamentally, it begins with saying no.

That’s why so many housing activists view Livable California and its platform in such cynical terms. The group may share a few strands of DNA with Marxist critiques and use the language of citizen empowerment, but to critics like Nall, it is a force of elitism. Proposition 13, California’s property tax freeze of the 1970s, and the appreciation of urban land in coastal communities created what he terms a “bizarre middle-class aristocracy” that’s based almost solely on homeownership. “Single-family zoning has a lot of parallels to aristocratic land-holding systems,” Nall told me. “It’s, ‘Protect our regime from these predatory outside capitalists who don’t have the noblesse oblige that we have for our communities.’”

Kirsch strongly disagrees with this line of thinking; to her, rejecting state intervention is a way to lift up local power, which can still shepherd development, slowly and incrementally. Communities like Mill Valley have taken steps that open doors, Kirsch said—including allowing backyard “granny flats” and creating a new development impact fee to fund affordable housing. She approvingly cites other kinds of housing efforts, too: “Bigger cities are looking at additional options like commercial linkage fees, employer head taxes, 100 percent affordable housing projects, and vacancy taxes, to name a few,” she wrote me in an email.

Of course, “local control” has often served to keep resources away from those suffering most acutely under California’s housing crisis. For two timely examples in the Bay Area, see the dueling GoFundMe pages over a proposed San Francisco homeless shelter, or the large mixed-use development in San Bruno, with 15 percent affordable units, that was killed by a single city councilmember objected to potential traffic impacts. Better citizen engagement processes would address the root of these conflicts, Kirsch believes, by getting a wider representation of people to influence decisions and connect on an empathic level. “It’s about engaging in conversations before jumping to conclusions about what to do,” she said. “You can’t come in with the solution too quickly.”

Here, I think, lies the great YIMBY-NIMBY divide: a matter of intention versus outcome. While some selfish or bigoted actors may be sheltering their property values behind calls for “local control,” the desire to protect local communities, by using slow and incremental processes, is legitimate. But the single-family zoning codes that NIMBYs champion aren’t working for California circa 2019, and nor are they biblical. YIMBYs are justly impatient for progress, and they’re appealing to democratic processes for change, too. Perhaps both sides of the housing debate would be served by not assuming the worst in the other.

In any case, Kirsch is no longer Livable California’s acting leader. She stepped down in June. Now, the group hopes to file a state ballot initiative that would curtail the state’s ability to pass legislation that would alter local zoning codes. That isn’t quite Kirsch’s style: She feels her strength is in educating people at the grassroots level.

Meanwhile, she wonders if the triumph of the California suburbs may be short-lived. The bills in Oregon and Minneapolis surprised Kirsch, especially since they succeeded in two places in which she once lived. She thought leaders there would know better than to give in to development pressures. “Maybe I’m out of step with my own roots and history and about what a better way is,” she said. “Maybe it’ll be California next. All I can say is, it’s troubling to me.”