A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Saturday, March 24, 2018

Friday, March 23, 2018

The Freeway Revolt of 1956-1966 proves Citizens can make a difference.

The Freeway Revolt

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Freeway protesters in City Hall, c. 1960

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Picketers protesting against the Southern Freeway marching at City Hall, April 18, 1961.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

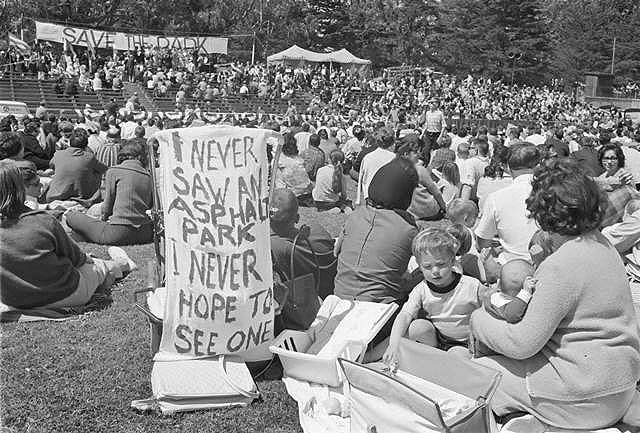

Save the Panhandle Park rally in Golden Gate Park, May 17, 1964.

Photo: Bancroft Library

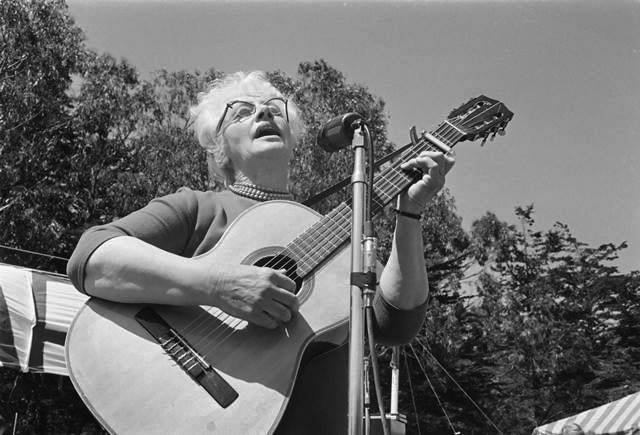

Malvina Reynolds sings her anti-freeway ballad at the May 17, 1964 rally to save the Panhandle in Golden Gate Park.

Photo: Bancroft Library

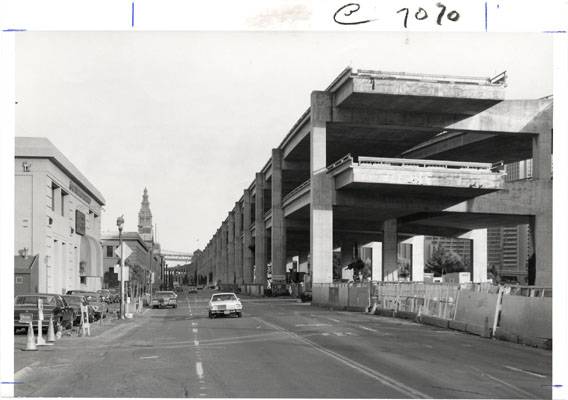

New ramps to Washington and Clay Streets from the Embarcadero Freeway, August 15, 1965.

Construction of the Embarcadero Freeway stopped here at Broadway due to popular anger.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Freeway protestors walk along Embarcadero, old Embarcadero Freeway and Ferry Building in background, c. 1964

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

In the 1950s, the California Division of Highways had a plan to extend freeways across San Francisco. At that time the freeway reigned supreme in California, but San Francisco harbored the seeds of an incipient revolt which ultimately saved several neighborhoods from the wrecking ball and also put up the first serious opposition to the post-WWII consensus on automobiles, freeways, and suburbanization.

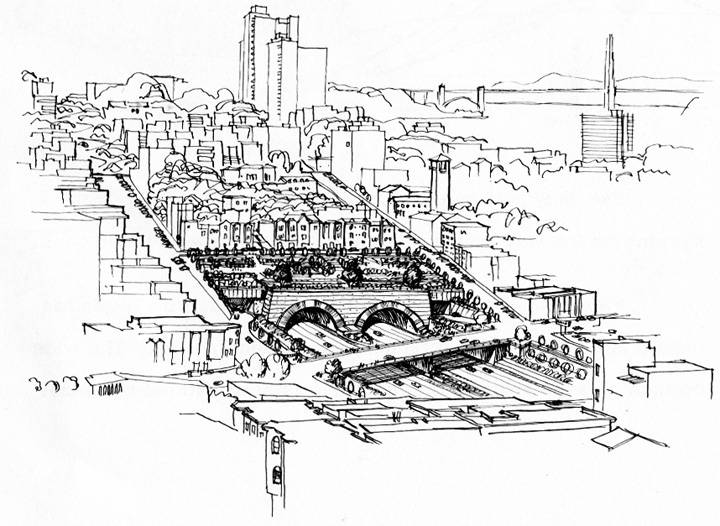

Early plan for 8-lane freeway to cut under Russian Hill on its way from the Embarcadero to the Golden Gate Bridge

The Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Council (HANC), one of the city's oldest and most persistent neighborhood groups, dates its origins to the initial struggles against the proposed Panhandle-Golden Gate Park freeway, which was to extend the central freeway up the Oak/Fell corridor, slice 60% of the Panhandle for the roadway, and tunnel under the north edge of Golden Gate Park before turning onto today's Park Presidio towards the Golden Gate Bridge.

On November 2, 1956 the San Francisco Chronicle graciously published a map of the proposed and actual freeway routes through San Francisco even though its accompanying editorial was already chastising protestors: "The remarkable aspect of these protests and claims of injury is their tardiness. They concern projects that have for years been set forth in master plans, surveys and expensive traffic studies. They have been ignored or overlooked by citizens and public official alike—until the time was at hand for concrete pouring and when revision had become either impossible or extremely costly. The evidence indicates that the citizenry never did know or had forgotten what freeways the planners had in mind for them."

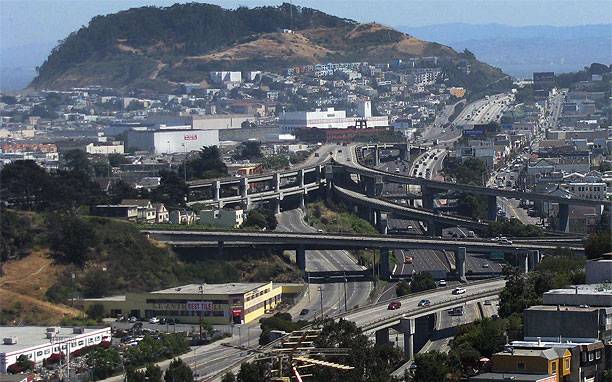

Highway 101 just south of Cesar Chavez exit, 2007

Photo: Chris Carlsson

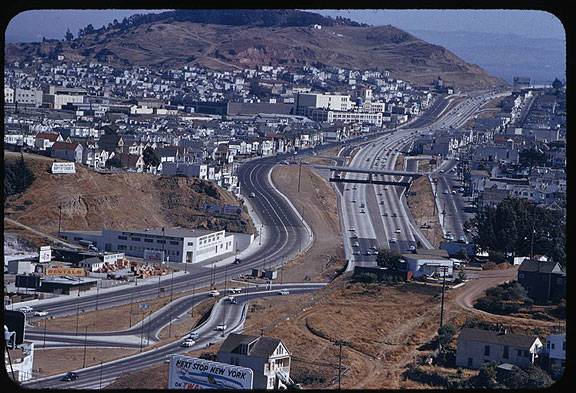

James Lick Freeway under construction in 1953: San Francisco's first. Seals Stadium, the old ballpark is visible in center-left of photo

Photo: Ed Brady

Just three years earlier San Francisco had opened what became known as "hospital curve" both for its location behind General Hospital and its high rate of accidents. On October 1, 1953 the Bayshore Freeway opened from Army to Bryant/7th Street, nearing a later direct link with the Bay Bridge. San Franciscans could now drive three unmolested miles of "divided no-stop freeways" from Alemany to Bryant. The new Bayshore Freeway was the first highway to open after the failed effort of state highway authorities to build a 2nd Bay Bridge right next to the first, a plan they pursued from 1945-49 before it was finally defeated, in part thanks to Mayor Elmer Robinson appealing to military authorities to halt it because it would reinforce the bottleneck the Bay Bridge already presented for getting in or out of the City.

California passed the Collier-Burns Act in 1947, which allowed the construction of freeways to proceed without charging tolls. The Act reoriented the state highway system from multipurpose rural roads to limited-access superhighways and extended them into the cities for the first time. The assumption, which was borne out by developments, is that by building the new highways into the cities, the state gas tax revenues (which were raised 50% in the same bill) would rise rapidly because of all the additional driving the highways promoted among urban dwellers. As it turns out, it was California’s lead that shaped the 1956 Interstate Highway System, which followed the same funding formula. As Katherine M. Johnson has written, the “major flaw of this solution to the rural bias of American highway[s] was precisely its fiscal logic.” Focusing on solving a funding problem ignored basic issues of design standards and integration into the urban fabric. Instead, new highways were marketed as solutions for urban blight, dovetailing with the massive urban renewal programs that were gutting central city neighborhoods in dozens of cities from the late 1950s into the 1970s.

As the plans unfolded, public opposition grew. By the time the Embarcadero Freeway was nearly under construction in 1958, a loud opposition had formed, going on to campaign for its removal after its completion. Over 30,000 people signed petitions at meetings organized in the Sunset, Telegraph and Russian Hills, Potrero, Polk Gulch and other threatened areas. In 1959 The Supervisors voted to cancel 75% of planned freeway routes through the city, much to the shock of the Department of Highways and the state government. But that was not the end of the freeway revolt.

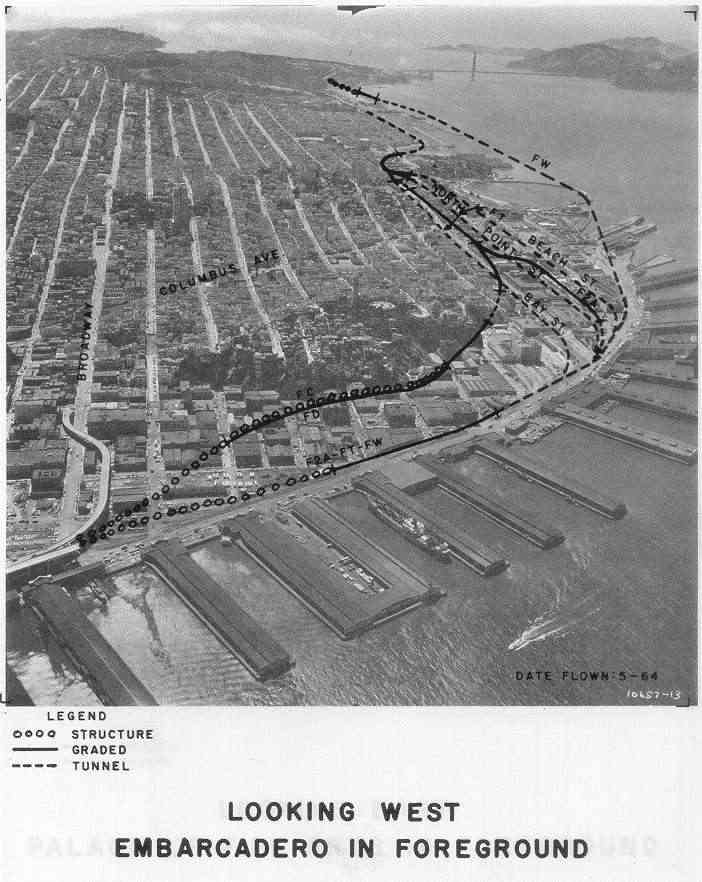

Proposed freeway routes

Freeway builders continued to resurrect various routes, encountering persistent, well-organized resistance by San Francisco neighborhoods, especially in the Sunset and Richmond where neighbors were dedicated to stopping the proposed Western Freeway. Supervisor William Blake was a key opponent of the freeway planners.

Lost in the story of the Freeway Revolt is the role it played in helping BART get institutional support. After the 1959 Supervisorial defeat of freeway plans, BART advocates got surplus Bay Bridge tolls allocated to the proposed transbay tube. After the 1961 vote against the Western Freeway, Mayor George Christopher and the influential Bay Area Council both endorsed the proposed BART system. As freeway proponents continued to advocate for their plans, Supervisor Blake proposed burying a freeway in a “crosstown” tunnel as an alternative to the “beautified” Panhandle freeway. But state highway officials derided it as an unrealistic and costly plan, and after a year of study, ruled it out. San Francisco officials, including new Mayor Jack Shelley, made it clear they wanted the Embarcadero Freeway taken down and replaced with an underground route, the proposed Golden Gate Freeway, that would connect to the Golden Gate Bridge.

In 1964 the Panhandle-Golden Gate Freeway plan reached a climax, with a May 17 rally at the Polo Grounds to save the Park, featuring a "Natural Anthem" and a dedicated tune by Malvina Reynolds, the famous left-wing folk singer, and a speech by poetKenneth Rexroth. Months later, in a final, climactic 6-5 vote, the Board of Supervisors rejected the Park Freeway on October 13. Black supervisor Terry Francois cast the deciding vote, delivering a point-by-point six-page rebuttal to the pro-freeway arguments. (It is interesting to note that the other No-votes on that Board were future mayor George Moscone, future CAO/auto dealer and consumer of sexual services Roger Boas, future Lt. Governor Leo McCarthy, William Blake and Clarissa McMahon. In favor of the freeway were "progressive" supervisors Jack Morrison, Joseph Casey, Jack Ertola, Joseph Tinney and Peter Tamaras.) Mayor Jack Shelley was all for it, as was the Labor Council from which he hailed. The Supervisors' Transportation Committee had received a petition with 15,000 signatures, 20,000 letters and telegrams, and had received opposition from 77 community organizations.

After all that, it seemed to be decided. But it wasn’t. More bureaucratic studies and fears of losing several hundred million in federal financing for the City’s highways led to another climax. In 1966, the Panhandle and Golden Gate Freeways were once again brought forward, pissing off the thousands of people who thought they’d already stopped the plans. Ultimatums from the State Highway Commission and much bluster from pro-freeway politicians failed to carry the day. Mobilized citizens and their community organizations won over organized labor, who now opposed the plans too, arguing that jobs would actually be lost if the city became “one long strip of concrete for commuters with bigger and better ghettoes.” Finally, on March 21, 1966 both the Panhandle and Golden Gate freeways were defeated 6-5 by Supervisorial votes.

New Bayshore Freeway soon after opening, April 7, 1955. View from Bernal Heights southeast, with Bayview Hill in background.

View southeast from Bernal Heights towards Bayview Hill, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Today, San Francisco's freeways have changed again, thanks to the Loma Prieta 1989 earthquake. The much maligned Embarcadero Freeway has been removed, as has an unsightly spur of the Central Freeway. A raging debate over the future of the Central Freeway ramps that go north across Market was finally resolved and has now been replaced by the surface Octavia Boulevard. The 101-280 interchange was a mess from 1989 to 1996. New offramps were added to I-280 to serve a new waterfront roadway and the planned Giants ballpark at China Basin in 1997, but no new freeways will be built in San Francisco. New transit money goes to BART and MUNI, while Caltrans and SF Dept. of Public Works continue to spend vast quantities of social wealth on maintaining the San Francisco road system. The rapid rise in value in both areas where freeways were removed, along the now open waterfront, as well as the rapidly gentrifying Hayes Valley/Civic Center area, show that profits can be drawn from forward looking urban planning, de-emphasizing cars and re-emphasizing neighborhood, community, and nature. But most U.S. urban planners still adhere religiously to the cult of the car, hence constant efforts to expand roads and parking at the expense of numerous more sensible alternatives, from decent mass transit to ubiquitous bikeways.

For a deeply detailed account of the 1956-66 freeway revolt, see Katherine M. Johnson’s article “Captain Blake versus the Highwaymen: Or, How San Francisco Won the Freeway Revolt” in Journal of Planning History 2009; 8; 56, originally published onlineNov. 28, 2008.

See also, William Issel's excellent article "Land Values, Human Values, and the Preservation of the City's Treasured Appearance: Environmentalism, Politics, and the San Francisco Freeway Revolt" in Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 4 (1999).

Thursday, March 22, 2018

Senator Wiener's War to upzone every city with SB827 in Marin County is going well

#WienersWar to upzone every city in California with SB827 is going well. If only he had funding for a few more of these cyborgs.

SB-827 and then, please click HERE to sign our online petition entitled; "NO on SB-827 & SB-828! Stop Top-Down Planning, Unsustainable High-Density Housing, and Unfunded Mandates" and spread the news!

SB-827 and then, please click HERE to sign our online petition entitled; "NO on SB-827 & SB-828! Stop Top-Down Planning, Unsustainable High-Density Housing, and Unfunded Mandates" and spread the news!

Everything Is On Sale Compared to 1979

Everything Is On Sale Compared to 1979

By Chelsea German and Marian TupyWage appreciation, or lack thereof, does not tell us everything we need to know about our standard of living. Wages often fail to capture changes that come from competition and technological breakthroughs.

One—much underutilized—way in which we can get a sense of the improvements in our standard of living is to look at the number of hours an average employee needs to work in order to buy commonly used items. When cost is measured in terms of hours worked, almost everything in 2015 is “on sale” when compared to the same product in 1979.

Consider two common kitchen appliances: the microwave and the refrigerator.

Those are some impressive discounts! Look at the data for yourself and you will find that the trend of falling prices, when measured in hours of labor, is widespread. The main exceptions when it comes to the cost of living are the highly distorted healthcare, education and housing markets. In contrast, when market competition thrives, it tends to bring down prices and raise living standards for all of us.

Topics: Economic Freedom, Technology, Wealth

Wednesday, March 21, 2018

Roller Derby Queen is not Forgotten

Lost, but not forgotten. Joanie Weston (January 20, 1935 – May 10, 1997), Roller Derby Queen, for the San Francisco Bay Bombers. AKA, the "Blonde Bomber".

Housing bill is going to raise cost for public services SIGN PETITION TODAY!

Dick Spotswood: Housing bill is going to raise cost for public services

POSTED: 03/17/18

Dick Spotswood

Here’s today’s test: If SB 827, legislation introduced by state Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, designed to up-zone most California suburbs is enacted, who’s going to pay its costs?

Wiener’s bill grants “by-right” permission to erect multi-unit dwellings up to eight stories tall within a quarter-mile of bus stops along streets where buses operate at least every 15 minutes during peak periods.

If it passes, say goodbye to local planning.

It’s part of the ongoing “war against suburbia” favored by big-city politicians and their construction, real estate and technology industry allies.

San Francisco, San Jose and similar booming locales are magnets for high-income technology jobs. That has caused rents to skyrocket and housing to become scarce.

It’s Wiener’s idea that adjacent small-town suburbs should become little big cities to provide cheap housing for urban workers.

SB 827 has major Marin implications.

The densification mandates will apply to all property one-quarter of a mile from bus stops up and down Highway 101; parts of Novato’s San Marin Drive, Novato Boulevard, Redwood Boulevard and Hamilton Parkway; San Rafael’s Third and Fourth streets and Francisco Boulevard; Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, from Manor Road in Fairfax to the Larkspur Ferry; Kentfield’s College Avenue, Magnolia Avenue in Larkspur and Tamalpais Drive in Corte Madera; Mill Valley’s Miller and East Blithedale avenues; Tam Junction’s Shoreline Highway; around the Strawberry Shopping Center and the length of Sausalito’s Bridgeway.

The up-zoning radius also extends a half-mile from Tiburon and Larkspur ferry terminals and from all SMART depots.

SB 827 is so bad it’s hard to believe it has a decent chance of passage in some form. Given the big bucks behind it, don’t underestimate its prospects.

I saw state Sen. Mike McGuire, D-Healdsburg, at the Democrats’ San Diego state convention. He rhetorically asked, “Who is going to pay for SB 827? Only three cities from the Golden Gate to the Oregon line have fire trucks that can handle eight-story buildings. What about water (for new residents)? Where does it come from?”

He could have also asked who pays for additional highway and transit capacity, larger schools and more police.

The cynicism behind this legislation is shameful. SB 827 includes a seemingly innocuous provision: “No reimbursement is required by this act pursuant to Section 6 of Article XIII-B of the California Constitution because a local agency or school district has the authority to levy services, charges, fees or assessments sufficient to pay for the programs or level of service mandates by this act within the meaning of Section 17556 of the Government Code.”

That’s boilerplate language routinely used in Sacramento to legally thwart the will of California voters. It’s no secret “we know best” solons are in the habit of instructing others but are loathe to pick up the resulting tab.

In 1979, voters approved Proposition 4, the “Gann Limit,” as a constitutional amendment requiring the state to reimburse local governments for costs of complying with state laws. When voters tried to force Sacramento to pay the piper, Government Code section 17556 emerged as a court-tested route to nullify the Gann Limit.

It provides if cities, counties or school districts theoretically can raise taxes to pay for whatever Sacramento tells them what to do, then legislators can cavalierly wash their hands of obligations to pay for their actions.

There’s one way to make Sacramento intellectually honest. Delete SB 827’s “no reimbursement” section.

If this miracle occurs, Wiener will have to find the cash needed for new public services necessitated by building inappropriate high-rise stack-and-pack suburban housing.

If the Legislature has to eliminate other pet programs to fund SB 827’s fiscal consequences, Wiener’s bill will soon experience an appropriate demise.

Columnist Dick Spotswood of Mill Valley writes about local issues on Sundays and Wednesdays. Email him at spotswood@comcast.net.

Please click HERE to sign our online petition entitled; "NO on SB-827 & SB-828! Stop Top-Down Planning, Unsustainable High-Density Housing, and Unfunded Mandates!"

POSTED: 03/17/18

Dick Spotswood

Here’s today’s test: If SB 827, legislation introduced by state Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, designed to up-zone most California suburbs is enacted, who’s going to pay its costs?

Wiener’s bill grants “by-right” permission to erect multi-unit dwellings up to eight stories tall within a quarter-mile of bus stops along streets where buses operate at least every 15 minutes during peak periods.

If it passes, say goodbye to local planning.

It’s part of the ongoing “war against suburbia” favored by big-city politicians and their construction, real estate and technology industry allies.

San Francisco, San Jose and similar booming locales are magnets for high-income technology jobs. That has caused rents to skyrocket and housing to become scarce.

It’s Wiener’s idea that adjacent small-town suburbs should become little big cities to provide cheap housing for urban workers.

SB 827 has major Marin implications.

The densification mandates will apply to all property one-quarter of a mile from bus stops up and down Highway 101; parts of Novato’s San Marin Drive, Novato Boulevard, Redwood Boulevard and Hamilton Parkway; San Rafael’s Third and Fourth streets and Francisco Boulevard; Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, from Manor Road in Fairfax to the Larkspur Ferry; Kentfield’s College Avenue, Magnolia Avenue in Larkspur and Tamalpais Drive in Corte Madera; Mill Valley’s Miller and East Blithedale avenues; Tam Junction’s Shoreline Highway; around the Strawberry Shopping Center and the length of Sausalito’s Bridgeway.

The up-zoning radius also extends a half-mile from Tiburon and Larkspur ferry terminals and from all SMART depots.

SB 827 is so bad it’s hard to believe it has a decent chance of passage in some form. Given the big bucks behind it, don’t underestimate its prospects.

I saw state Sen. Mike McGuire, D-Healdsburg, at the Democrats’ San Diego state convention. He rhetorically asked, “Who is going to pay for SB 827? Only three cities from the Golden Gate to the Oregon line have fire trucks that can handle eight-story buildings. What about water (for new residents)? Where does it come from?”

He could have also asked who pays for additional highway and transit capacity, larger schools and more police.

The cynicism behind this legislation is shameful. SB 827 includes a seemingly innocuous provision: “No reimbursement is required by this act pursuant to Section 6 of Article XIII-B of the California Constitution because a local agency or school district has the authority to levy services, charges, fees or assessments sufficient to pay for the programs or level of service mandates by this act within the meaning of Section 17556 of the Government Code.”

That’s boilerplate language routinely used in Sacramento to legally thwart the will of California voters. It’s no secret “we know best” solons are in the habit of instructing others but are loathe to pick up the resulting tab.

In 1979, voters approved Proposition 4, the “Gann Limit,” as a constitutional amendment requiring the state to reimburse local governments for costs of complying with state laws. When voters tried to force Sacramento to pay the piper, Government Code section 17556 emerged as a court-tested route to nullify the Gann Limit.

It provides if cities, counties or school districts theoretically can raise taxes to pay for whatever Sacramento tells them what to do, then legislators can cavalierly wash their hands of obligations to pay for their actions.

There’s one way to make Sacramento intellectually honest. Delete SB 827’s “no reimbursement” section.

If this miracle occurs, Wiener will have to find the cash needed for new public services necessitated by building inappropriate high-rise stack-and-pack suburban housing.

If the Legislature has to eliminate other pet programs to fund SB 827’s fiscal consequences, Wiener’s bill will soon experience an appropriate demise.

Columnist Dick Spotswood of Mill Valley writes about local issues on Sundays and Wednesdays. Email him at spotswood@comcast.net.

Please click HERE to sign our online petition entitled; "NO on SB-827 & SB-828! Stop Top-Down Planning, Unsustainable High-Density Housing, and Unfunded Mandates!"

SF Planning Commission cringes at Wiener’s transit-housing bill

“A recipe for Beverly Hills in the Sunset”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59059535/Pi.1415926535.0.jpeg)

When State Senator Scott Wiener introduced his SB 827 bill, which would place restrictions on the kinds of height limits that cities can impose on parcels “within a a half mile radius of a major transit stop or a quarter mile radius of a high-quality transit corridor,” the first question on everyone’s mind was, “Doesn’t that mean basically all of San Francisco?”

Well, according to the map included in a report presented to the San Francisco Planning Commission Thursday it seems that, yes, in its present form SB 827 would effectively up-zone some 96 percent of city parcels.

“This is our best guess,” planner Paolo Ikezoe cautioned commissioners on Thursday, noting that SB 827 will certainly be further amended in the future and also that the city does not yet have “completely accurate GPS data on street width,” which determines the specific heights necessitated on blocks.

Nevertheless, Izekoe told the commission, “On any parcel [marked on the map] a developer would be entitled to ask for a transit rich bonus. The city would be prohibited from enforcing a height limit lower than 55 or 85 feet” depending on the street.

While this would mean no change from the present zoning for streets in areas already fairly tall and dense, the ramifications for low-lying residential neighborhoods on the west side of the city are profound.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442235/25.jpg)

Most of the commission reacted to the bill like a used Kleenex. Commissioner Dennis Richards, after showing a diagram of every housing law presently being considered by the state, called the effect “a full-frontal offensive on local controls” and dubbed SB 827 “a recipe for Beverly Hills in the Sunset.”

“What do we have left to actually decide [if the new laws pass]?” Richards wondered. “What else are we going to sit here for?”

Commissioner Kathrin Moore was even more dour, calling the law “the antithesis of planning” and a “dictatorial, Trump-like” bid to sap local authority.

“I do not understand how a former supervisor can be so unappreciative and non-understanding of the dynamics of what this city can do,” said Moore.

On the other hand, Commissioner Rich Hillis, while noting that he too found the bill in its present form too broad, said, “I applaud Scott Wiener, I think he’s got the broad interests of California in mind.”

Hillis notes that he probably wouldn’t be able to afford San Francisco on the salary he made when moving here 25 years ago and cautioned, “People want to move to California, we’re not going to stop them.”

Chief among the complaints is the characterization of the bill as “one size fits all,” as planners and commissioners griped that it treats San Francisco, which has accelerated housing construction in recent years, no different from cities that have scarcely bothered to build at all.

Earlier in the week the Board of Supervisors’ Land Use Committee took up a similar complaint in the form of Supervisor Aaron Peskin’s “Resolution Opposing California Senate Bill 827,” which also decries the broadness of the potential law’s effects.

“California State Senate Bill (SB) 827 would apply to virtually all residential parcels citywide based on the prescribed radii,” the resolution complains, adding that this would “effectively [allow] the State to override San Francisco’s charter authority, circumvent local planning laws and incentivize speculation.”

Despite complaints, Sen. Wiener characterizes the bill as a necessary spur to get reluctant cities to build more and has promised more amendments in the future to address some of the criticisms.

YIMBY uses "age shaming" to build support for SB827

#YIMBYS keeping it classy. Why not just throw Grandma out on the street so this "deserving" millennial can have an affordable place to sleep after slaving all day behind a computer and earning six figures? After all, he is the future.

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

Monday, March 19, 2018

Sunday, March 18, 2018

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442287/Steve_Morgan.jpg)