A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Saturday, January 12, 2019

Friday, January 11, 2019

The Suburbs: Planners, Smart Growth and the Manhattan Illusion

Excellent 6 minute video critique of Smart Growth in Southern California

"If you really believe that suburbs are going to die, then let them die, and let the market address the situation" says Joel Kotkin, Chapman University professor and urban planning specialist.

But letting the market work is far from ideal for California's regional planners and local politicians, who want almost 70 percent of new housing over the next 25 years to be multi-unit apartment-style dwelliings, despite the facts that more than half of Southern California households reside in a single-family home and that more people are leaving California than are coming in.

"In a great nation like ours, you can't let people do what they want. It has to be coordinated," says Hasan Ikhrata, the executive director of the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG). Ikhrata's group, which directs planning for the Southern California region via subsidies and contracting with big developers, foresees a future in which Southern California is dense, full of high-rise buildings, and connected by rail, much like New York City.

The problem is, LA isn't New York. No city but New York is New York, and attempts to force high-density, New York-style development onto areas that don't need it can result in terrible unintended consequences.

"Many people see a light rail and think the San Francisco trolley line," says Damien Goodmon, spokesman for the Crenshaw Subway Coalition. He lives in LA's historical black neighborhood Leimert Park and has seen the effects bad planning can have on established communities.

"You can have transit riders and still destroy a community," says Goodmon.

And the ultimate irony of the unending push for high-density planning in sprawling Southern California is that while, yes, Manhattan is denser than LA, if you zoom out a bit, LA-Long Beach-Anaheim is already the densest urban region in the United States. That happened without any sustained, conscious high-density housing development or state-of-the-art rail transit.

"One of the things that happens when you force this kind of high-density development is you destroy the very urban neighborhoods that retain the middle class," says Kotkin. "The neighborhoods have to fight this kind of guerilla-style."

But letting the market work is far from ideal for California's regional planners and local politicians, who want almost 70 percent of new housing over the next 25 years to be multi-unit apartment-style dwelliings, despite the facts that more than half of Southern California households reside in a single-family home and that more people are leaving California than are coming in.

"In a great nation like ours, you can't let people do what they want. It has to be coordinated," says Hasan Ikhrata, the executive director of the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG). Ikhrata's group, which directs planning for the Southern California region via subsidies and contracting with big developers, foresees a future in which Southern California is dense, full of high-rise buildings, and connected by rail, much like New York City.

The problem is, LA isn't New York. No city but New York is New York, and attempts to force high-density, New York-style development onto areas that don't need it can result in terrible unintended consequences.

"Many people see a light rail and think the San Francisco trolley line," says Damien Goodmon, spokesman for the Crenshaw Subway Coalition. He lives in LA's historical black neighborhood Leimert Park and has seen the effects bad planning can have on established communities.

"You can have transit riders and still destroy a community," says Goodmon.

And the ultimate irony of the unending push for high-density planning in sprawling Southern California is that while, yes, Manhattan is denser than LA, if you zoom out a bit, LA-Long Beach-Anaheim is already the densest urban region in the United States. That happened without any sustained, conscious high-density housing development or state-of-the-art rail transit.

"One of the things that happens when you force this kind of high-density development is you destroy the very urban neighborhoods that retain the middle class," says Kotkin. "The neighborhoods have to fight this kind of guerilla-style."

Marin is greenwashing urban growth.

Labels:

ABAG,

HCD,

HUD,

Joel Kotkin,

MTC,

One Bay Area Plan,

smart growth,

Video

Thursday, January 10, 2019

Sea Level Rise Presentation at the Marin Coalition on 1/9/2019

Leslie Lacko – Sea Level Rise Planner, Marin County Community Development Agency · James Raives – Senior Open Space Planner, Marin County Parks and Open Space Marin County already floods during heavy rains and King Tides. How will rising sea level further impact our shoreline? How can we adapt and what is the County doing to prepare? Local governments must chart new ground in planning for climate change and Marin County is leading the way. Hear answers to these questions and more from staff members who do the hands-on work of preparing Marin County for sea level rise.

Marin County Planner explains McInnis Levee Project 1/9/2019

Marin County Open Space planner explains the proposed McInnis Wetlands restoration and levee and its affect on Silveira Ranch and Santa Venetia. 13 minutes of a longer presentation.

Wednesday, January 9, 2019

Dick Spotswood: Planners keep pushing the bogus concept of transit-centered housing

Dick Spotswood: Planners keep pushing the bogus concept of transit-centered housing

By DICK SPOTSWOOD | spotswood@comcast.net |

January 8, 2019 at 10:00 am

Regional governments tout the benefits of so-called transit-centered housing. The concept is at the heart of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s CASA (Committee to House the Bay Area) compact and San Francisco Democrat Sen. Scott Wiener’s new Senate Bill 50.

Superficially, it appears logical that people living in high-density apartments adjacent to rail, bus or ferry transit stops won’t need an auto to commute to work. Instead, they’ll take transit because it’s more convenient.

The reality isn’t so simple.

With transit-centered housing, the image that pops to mind includes a Manhattan or at least a central San Francisco, Philadelphia or Chicago level of public transit. There, with a century’s worth of transit infrastructure, they’ve crafted their bus/rail network to a stage of development where virtually every origin and destination is connected.

That’s crucial, because the 2019 commute doesn’t resemble the days of old when Bay Area suburban commuters were mostly headed to one destination: downtown San Francisco. Today’s commute, often involving two-employed resident households, resembles the crisscrossed lines of an old telephone switchboard running all over the Bay Area.

No doubt our region would be better served by a comprehensive transit network similar to that in greater London. To get there is enormously expensive and will, with America’s endless environmental reviews and litigious culture, literally take a century.

Let’s see if transit-centered housing works as promised in Marin. Presume our typical commuter lives at Corte Madera’s Tam Ridge Apartments, aka WinCup. The four-story 180-unit high-density complex is exactly the housing envisioned in SB 50. When approved, WinCup was touted as transit-centered housing next to a Highway 101 trunk line bus stop.

The time selected for this exercise is the 8 a.m. morning weekday commute. The destinations are six Bay Area employment centers. It’s a fair time for a test, because traffic is heavy and transit frequencies (public transportation such as bus, train or ferry) at their maximum. Travel time from WinCup to each destination by auto and transit is estimated using the smartphone Google map app.

From WinCup to:

• Montgomery and Market streets: auto, 33 minutes; transit, 55 minutes.

• UC Mission Bay Medical Center: auto, 42 minutes; transit, 1 hour, 18 minutes.

• UC Berkeley: auto, 28 minutes; transit, 1 hour, 40 minutes, via San Francisco.

• Santa Rosa’s Old Courthouse Square: auto, 41 minutes; transit, 1 hour, 43 minutes.

• San Francisco State University: auto, 28 minutes; transit, 1 hour, 13 minutes.

• Oakland’s Alameda County Courthouse: auto, 27 minutes; transit, 1 hour, 17 minutes.

The transit commute from WinCup to downtown San Francisco and UC Mission Bay is competitive with driving. The ease of bus travel versus driving and parking makes it viable. Not so, trips from WinCup to San Francisco State, downtown Oakland, Santa Rosa or UC Berkeley. Ditto for jobs in San Mateo County. New Tam Ridge residents – much less those living farther afield – are necessarily going to drive to those jobs. SEE the Full Article HERE

Monday, January 7, 2019

Gavin Newsom’s keeping it all in the family

Gavin Newsom’s keeping it all in the family

Gavin Newsom’s keeping it all in the family

By Dan Walters | Jan. 6, 2019 | COMMENTARY, DAN WALTERS

|

| Ties among the Brown, Newsom, Pelosi and Getty families date back three generations. |

Gavin Newsom will be the first Democrat in more than a century to succeed another Democrat as governor and the succession also marks a big generational transition in California politics.

A long-dominant geriatric quartet from the San Francisco Bay Area – Gov. Jerry Brown, Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi – has been slowly ceding power to younger political strivers.

Moreover, Newsom is succeeding someone who could be considered his quasi-uncle, since his inauguration continues the decades-long saga of four San Francisco families intertwined by blood, by marriage, by money, by culture and, of course, by politics – the Browns, the Newsoms, the Pelosis and the Gettys.

The connections date back at least 80 years, to when Jerry Brown’s father, Pat Brown, ran for San Francisco district attorney, losing in 1939 but winning in 1943, with the help of his close friend and Gavin Newsom’s grandfather, businessman William Newsom.

Fast forward two decades. Gov. Pat Brown’s administration developed Squaw Valley for the 1960s winter Olympics and afterward awarded a concession to operate it to William Newsom and his partner, John Pelosi.

One of the Pelosis’ sons, Paul, married Nancy D’Alesandro, who went into politics and has now reclaimed speakership of the House of Representatives. Another Pelosi son married William Newsom’s daughter, Barbara. Until they divorced, that made Nancy Pelosi something like an aunt by marriage to Gavin Newson (Nancy Pelosi’s brother-in-law was Gavin Newsom’s uncle).

The Squaw Valley concession was controversial at the time and created something of a rupture between the two old friends.

William Newsom wanted to make significant improvements to the ski complex, including a convention center, but Brown’s Department of Parks and Recreation balked. Newsom and his son, an attorney also named William, held a series of contentious meetings with officials over the issue.

An eight-page memo about those 1966 meetings from the department’s director, Fred Jones, buried in the Pat Brown archives, describes the Newsoms as being embittered and the senior Newsom threatening to “hurt the governor politically” as Brown ran for a third term that year against Ronald Reagan.

Pat Brown’s bid for a third term failed, and the Reagan administration later bought out the Newsom concession. But the Brown-Newsom connection continued as Brown’s son, Jerry, reclaimed the governorship in 1974. He appointed the younger William Newsom, a personal friend and Gavin’s father, to a Placer County judgeship in 1975 and three years later to the state Court of Appeal.

Justice Newsom, who died a few weeks ago, had been an attorney for oil magnate J. Paul Getty, most famously delivering $3 million to Italian kidnapers of Getty’s grandson in 1973. While serving on the appellate bench in the 1980s, he helped Getty’s son, Gordon, secure a change in state trust law that allowed him to claim his share of a multi-heir trust.

After Newsom retired from the bench in 1995, he became administrator of Gordon Getty’s own trust, telling one interviewer, “I make my living working for Gordon Getty.” The trust provided seed money for the PlumpJack chain of restaurants and wine shops that Newson’s son, Gavin, and Gordon Getty’s son, Billy, developed, the first being in a Squaw Valley hotel.

Gavin Newsom had been informally adopted by the Gettys after his parents divorced, returning a similar favor that the Newsom family had done for a young Gordon Getty many years earlier. Newsom’s PlumpJack business (named for an opera that Gordon Getty wrote) led to a career in San Francisco politics, a stint as mayor, the lieutenant governorship and now to the governorship, succeeding his father’s old friend.

He’s keeping it all in the extended family.

Miller Creek Watershed

Miller Creek Watershed

History and Habitat

Human Settlement

The Miller Creek Watershed is the northernmost part of the north San Rafael land grant (San Pedro, Santa Margarita y Las Gallinas). The land was originally granted to Timothy Murphy who incurred the gratitude of Governor Alvarado in 1837 by helping him defend against a coup attempt.

James Miller later bought 680 acres of the Las Gallinas portion of the rancho and operated it as a beef ranch and then as a dairy farm. Miller assisted the Sisters of Charity running the St. Vincent School, established 1855 as a girls’ seminary. The school eventually closed due to a lack of students and later became a school for orphaned boys.

The valley portions of the watershed were developed for urban housing beginning in 1955. The most recent development, Miller Creek Estates, was constructed in the 1980s and early 90s.

Changes to Watershed Processes

Miller Creek is an atypical east Marin creek in that it has a relatively intact riparian area with very high widths and depths relative to its drainage area. In many locations throughout Miller Creek the banks are 20 to 25 feet high and its width is often over 100 feet (Philip Williams and Associates, Ltd. 19811).

The creek has gone through two recent cycles of incision, or arroyo formation since the arrival of Europeans. Mid 19th century riparian vegetation clearing and grazing practices initiated the first cycle of channel downcutting. A second cycle started after the 1940s as evidenced by the disparate channel bed elevations upstream and downstream of the Grady Bridge and concrete apron installed in 1941; the channel downstream is 10 feet lower than the bed immediately upstream. Increased runoff and changes to drainage patterns from valley housing developments may have contributed to this rapid lowering of the channel bed. This incision occurred at a rate of approximately 1 foot per 10 years (PWA 1981). Recent channel assessments indicate that the rate of mainstem incision has slowed or stopped due to either the channel reaching a stable bed condition, increased sediment supply from tributary incision, or the installation of grade stabilization structures (Yin and Pope-Daum 2004 2).

With channel incision comes bank instability and widening. Vertical banks are undercut by moderate flows, with bank slumping and retreat occurring until there is sufficient width to accommodate flood flows and develop inset floodplains and terraces.

In the lower reaches of the valley the channel is wide with well developed and vegetated inset floodplains and an inner terrace. Bank instability at the outside bends of the channel meanders occurs throughout the valley as the channel continues to widen.

The Miller Creek Estates and Upper Miller Creek channel reaches were graded into a trapezoidal channel during housing development construction in the 1970s and 1980s. These reaches have a 100 foot setback along the channels. A post- project evaluation of this stretch of Miller Creek by Yin and Pope-Daum (2004) indicates that riparian vegetation has established in these reaches and the creek has developed a low-flow channel and discontinuous floodplains. Bank erosion is concentrated at the outside of meander bends. The channel complexity and habitat features are not as well developed as in the non-graded reaches downstream; however, the Miller Creek Estate reach has better habitat conditions than have been observed in the upstream reaches that are characterized by vertical banks, a wide homogenous channel bottom, and little mature riparian vegetation.

Tributary channels have undergone extensive downcutting and gully formation in response to the main channel incision. Headcut retreat is occurring in many steep, first order channels. Large volumes of sediment are delivered to the mainstem from tributary erosion and fine sediment aggradation reduces pool depths and degrades spawning gravels. The sediment produced by the upper watershed is deposited in the lower reaches of the system.

Downstream of the NWPRR Bridge the channel was rerouted and channelized in the 1920s. The creek was routed to the south, extended, and placed into a narrow, leveed channel with two 90 degree bends before reaching San Pablo Bay. A stretch of tidal wetlands are present along the bay front. There is local interest in realigning the creek east of the NWPRR Bridge to provide a more natural, direct connection to San Pablo Bay (Marin Conservation League 1997 3; St. Vincent’s/Silveira Advisory Task Force 2000 4).

Bank erosion in mainstem Miller Creek is widespread, as the channel is deeply incised in many places and in a widening phase. This erosion typically occurs on the outside of meander bends and is characterized by vertical banks with little to no riparian vegetation (H.T. Harvey and Associates 1992 5, PCI 2004 6). Often this bank erosion jeopardizes private property and structures.

Historic grazing practices and recent mainstem channel incision has caused destabilization of tributary channels. In the uplands, first and second order channels are undergoing headcutting and gully development, delivering fine sediment to Miller Creek during storm events. Visual assessments of instream sediment deposits indicate that there may be a higher than normal amount of fine sediment in the system, which leads to degraded instream habitat for fish and other species.

Habitat Types

The Miller Creek watershed is a mosaic of open ridge lands and grazing lands in the upper watershed, residential and limited commercial development along the narrow valley floor, and lower baylands. It is a relatively urbanized watershed but still supports a small population of steelhead, an important resource for the regional fishery. Some stretches of the creek still support somewhat healthy riparian plant communities. The lower marsh habitats represent some of the largest remaining tidally-influenced habitats in the bay region and support abundant waterfowl populations (Goals Project 1999 7)The Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District reclamation ponds adjacent to the marshes are one of the premier birding spots in Marin County. The Marin Countywide Plan (OS2.4) identifies Miller Creek as an important area for habitat connectivity providing continuous natural area through Miller Creek and Marinwood to the Bay.

The watershed is composed primarily of annual grasslands interspersed with oak-bay woodland and oak savanna in the upper watershed with patches of chaparral. The upper watershed is largely Marin County Open Space ridge lands and grazing lands. Historically, the upper watershed was heavily grazed and the riparian habitat is somewhat degraded. The most well-developed riparian plant communities occur west of Highway 101 near Miller Creek Middle School upstream towards Mt. Shasta Drive. Urban areas dominate the middle reaches of the watershed and the bulk of the population is concentrated along the narrow valley floor.

The lower reaches of the watershed east of Highway 101 support saltwater marsh and brackish-water marsh, both subject to tidal action. Freshwater seasonal wetlands occur in areas that were once historical baylands. These areas were diked off to provide agricultural land and now support oat hay production. The reclamation ponds created by Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District adjacent to tidal marshes in the lower watershed provide critical habitat for a number of bird species. This area boasts over 200 bird species and includes such sightings as golden eagle, ferruginous hawk, and rails. River otters are also known to frequent the area.

The St. Vincent’s School for Boys and Silveira Ranch are treasured parts of the Marin County landscape and provide critical habitat within the lower Miller Creek watershed. The site supports “oak woodlands, valley oak savanna, tidal and seasonal wetlands, historic diked tidelands, seeps and swales, the Miller Creek riparian corridor, and grassland” habitats (St. Vincent’s/Silveira Advisory Task Force 2000). Pacheco Ridge at the upper elevations of site supports intact native oak woodlands, an important habitat resource and community separator. The central location of the site provides habitat connectivity between “the Gallinas Creek watershed to the south, San Pablo Bay to the east, and Hamilton tidal marshes to the north” (St. Vincent’s/Silveira Advisory Task Force 2000).

Fish and Wildlife

The watershed supports a number of special-status plants and animals. Of particular interest are the occurrences of wetland-adapted species along the lower baylands. Noteworthy species include San Pablo song sparrow, California black rail, saltmarsh harvest mouse, and California clapper rail.

The Miller Creek watershed is also known to support 7 extant fish species (6 native and 1 introduced) and one extinct native species (Leidy 2007 8). Native species include California roach, steelhead, threepine stickleback, staghorn sculpin, prickly sculpin, and riffle sculpin. Common carp have also been introduced. Historically, the watershed supported native Sacramento sucker.

Steelhead have been observed within the Miller Creek watershed as recently as 2006.

There are no reported occurrences of federally-listed as threatened and California Species of Special Concern California red-legged frog within the watershed (CDFG 2008 9).

Heron and egret nesting colonies have been monitored by Audubon Canyon Ranch since the early 1990s (Kelly, et al., 2006). There are active nest colonies on shrub-covered islands at Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District plant at the east end of Smith Ranch Road. Black-crowned night-heron, snowy egret, and great egret have been observed nesting on the islands. Nests are in low-growing (1 meter) shrubs (Condenso, personal communication, May 15, 2008; Kelly, et al., 2006 10).

In addition, the Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District reclamation ponds support over 200 bird species.

Human Habitation and Land Use

Current land use

In 1960, Marinwood, Miller Creek, and associated communities organized a community services district responsible for fire protection, parks and recreation, street lighting and open space. The Marinwood Community Services District now owns 812 acres of open space in the watershed including part of the ridge between the Miller Creek watershed and Novato. The developed area of the watershed fills the valley, with large portions of the ridges in Marin County Open Space District ownership and the balance held in private ranches. 13% of the watershed is incorporated areas.

The Marin County Open Space District, City of San Rafael, and Marinwood Community Services District also own substantive portions of the Miller Creek riparian area.

Marin County has identified the Marinwood Shopping Center as a potential site for community-based planning creating workforce housing within the City-Center corridor in mixed-use development. The Countywide Plan calls for 50-100 units in this area, as per the Marinwood Plaza Conceptual Master Plan.

1 Land & Water Management for Upper Miller Creek and Environs

2 Post project evaluation, Miller Creek, California: assessment of stream bed morphology, and recommendations for future study

3 Miller Creek Restoration Feasability Study Calfed Proposal 1997 category III

4 St. Vincent's/Silveira Advisory Task Force Recommendations

5 Channel Stabilization and Restoration Design for Two Sites on Miller Creek Marinwood CSD Reach, San Rafael, CA

6 Summary of channel assessment and design for Miller Creek Lassen-Shasta Reach (aka Darwin Reach)

7 Baylands Ecosystem Habitat Goals: A Report of Habitat Recommendations

8 Robert A. Leidy, Ecology, Assemblage Structure, Distribution & Status of Fishes in Streams Tributary to the San Francisco Estuary

9 California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG). 2008. California Natural Diversity Database. California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento, CA.

10 Annotated Atlas and Implications for the Conservation of Heron and Egret Nesting Colonies in the San Francisco Bay Area

Fish

Vegetation

Land Use

Imperviousness

Large detailed versions of

these maps are available

in the Resources section.

A Generation plans an exodus from California

A Generation plans an exodus from California

Is it time to pack up and head East? Some small companies in Southern California are moving logistics operations to Texas and other neighboring states to reduce overhead. (iStockphoto)

By JOEL KOTKIN and WENDELL COX | Orange County Register

PUBLISHED: September 8, 2018 at 5:30 pm | UPDATED: September 10, 2018 at 3:10 pm

California is the great role model for America, particularly if you read the Eastern press. Yet few boosters have yet to confront the fact that the state is continuing to hemorrhage people at a higher rate, with particular losses among the family-formation age demographic critical to California’s future.

Since the recovery began in 2010, California’s net domestic out-migration, according to the American community survey, has almost tripled to 140,000 annually. Over that time, the state has lost half a million net migrants with the bulk of that coming from the Los Angeles-Orange County area.

In contrast, during the first years of the decade the Bay Area, particularly San Francisco, enjoyed a renaissance of in-migration, something not seen since before 2000. But that is changing. A recent Redfin report suggests that the Bay Area, the focal point of California’s boom, now leads the country in outbound home searches, which could suggest a further worsening of the trend.

Who’s leaving?

The reality, however, is more complicated than that. An analysis of IRS data from 2015-16, the latest available, shows that while roughly half those leaving the state made under $50,000 annually, half made above that. Roughly one in four made over $100,000 and another quarter earned a middle-class paycheck between $50,000 and $100,000. We also lose among the wealthiest segment, the people best able to withstand California’s costs, but by much smaller percentages.

The key issue for California, however, lies with the exodus of people around child-bearing years. The largest group leaving the state — some 28 percent — is 35 to 44, the prime ages for families. Another third come from those 26 to 34 and 45 to 54, also often the age of parents.

The key: Too expensive housing, not enough high-wage jobs

High housing prices hurt most young, middle-class and aspiring, often minority, working-class families. California’s prices are particularly bloated, over 161 percent higher, in comparison with national averages, in the lower-end “starter home” category. In Los Angeles and the Bay Area, a monthly mortgage takes, on average, close to 40 percent of income, compared to 15 percent nationally

Over time these factors — along with prospects of reduced immigration — will impact severely the state’s future. California is already seeing its population aged 6 to 17 decline. This reflects a continued drop in fertility in comparison to less regulated, and less costly, states such as Utah, Texas and Tennessee. These areas are generally those experiencing the biggest surge in millennial populations.

Progressive or regressive?

The old folks are not the ones most alienated. A survey by the UCLA Luskin School suggests that 18-to-29-year-olds are the least satisfied with life in Los Angeles while seniors were most positive. In the Bay Area, according to ULI, 74 percent of millennials are considering an exodus. It appears paying high prices to live permanently as renters in dense, small apartments — the lifestyle most promoted by planners, the media and the state — may not be as attractive as advertised.

California’s media and political elites like to bask in the mirror and praise their political correctness. They focus on passing laws about banning straws, the makeup of corporate boards, prohibiting advertising for unenlightened fundamentalist preaching or staging a non-stop, largely ineffective climate change passion play. Yet what our state really needs are leaders interested in addressing more basic issues such as middle-class jobs and affordable single-family housing.

The question is not how to handle a surge of new Californians, but how to prevent a greater exodus and perhaps even de-population. If that means replacing our current densification mantra with something that meets our demographic needs, so be it.

Joel Kotkin is the R.C. Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University in Orange and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism (www.opportunityurbanism.org). Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, a St. Louis-based public policy firm, and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission.

Sunday, January 6, 2019

FABLE: The Country Bumpkin and the Hobgoblin

Behind the town of Morlaix there is a beautiful glen which shelters many fine farms where cattle are bred and corn is grown. Here, long ago, one of the largest of these farms was tenanted by a good man whose name was Jalm. His only child, Barbaik, was a girl whose beauty was the boast of the countryside. Her face was lovely as a June rose, and her figure had all the charm of glowing youth and grace. And she was considered the best dancer and the daintiest heiress in all that broad country.

On Sundays, when she went to St. Mathew's church, she wore an embroidered cap, and a kerchief with large flowers on it. And she had five skirts, worn one above the other. Some of the old wives shook their heads as she went by and asked if she had sold the black hen to Old Nick and had thus gotten by uncanny means both beauty and fine clothes.

But Barbaik, who really was rather vain, cared nothing for what they said so long as she knew that she was the best dressed girl in the parish and the one after whom the lads ran. For that is what always happens. The hearts of young men are like wisps of straw hanging on a bush, and the beauty of maids is like the wind that carries them along in its train.

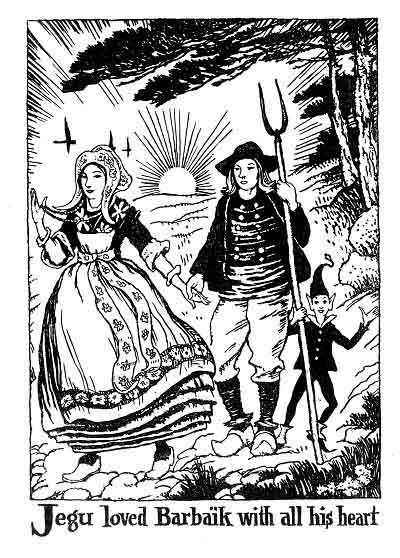

Among Barbaik's suitors there was one who loved her more than all the others. He was her father's farm hand, Jegu, a steadfast and upright Christian. But, alas, he was as rough as a Northerner and as ugly as a tailor. Barbaik would not listen to him in spite of all his merits. She always laughed and spoke of him as "the country bumpkin."

But Jegu loved her with all his heart. He bore all her insults and allowed himself to be badly treated by the girl who made joy and grief for him.

Now one evening as he was bringing his horses back from the pasture he stopped at a quiet pool to let them drink. He stood near the smaller horse, his head fallen on his breast. From time to time he would heave a sigh, for he was thinking of Barbaik. Suddenly a voice spoke to him, seemingly coming from the reeds that grew by the edge of the pool.

"Jegu, why are you grieving so?" the voice inquired. "You are not done for yet."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)