A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

A Citizen strikes back at the Bay Area Council demand for a Regional Power

Bay Area needs powerful regional government to keep economy vibrant, study says

The full report is online at www.bayareaeconomy.org

By Andrew McGall

amcgall@bayareanewsgroup.com

Posted: 11/06/2015 02:32:23 PM PST

Nowhere in this article is there any mention of climate change, green house gas emission reductions, carbon or the State legislation that addresses this issue (AB32, SB375). What does that tell you about how the "climate imperative" is being viewed by this organization? Climate change appears to be a means to an end, which apparently has nothing to do with the issues raised in this article.

Lack of inclusion of climate change looks like a duplicitous narrative on the topic of regionalism.

The use (or misuse) of language is the most significant aspect of the regionalism issue. Do not be deceived by language. Your ignorance and apathy are the keys to the success of this regionalism effort.

The Bay Area generates one of the brightest sparks in the nation's recovering economy, but feeding its vitality means residents will have to give up some local control, dig deeper into their wallets, and make room for tens of thousands of new neighbors, according to study released Friday.

Creating the artificial trade off to advance an agenda. Give up your freedom, your money and your lifestyle because we want control over you. Corporate America will run things from now on.

Keeping on prosperity's path requires a regional government with power to overcome local obstacles, money from new taxes and tolls, and opening the doors to housing closed by local growth controls and state environmental red tape, according to "A Roadmap for Economic Resilience," an in-depth study done by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

The Bay Area Economic Institute is the Bay Area Council is the corporate control of our nine counties, our state, possibly our nation and one of many implementing sustainable development.

Without action, the Bay Area's highways choked with commuters, its fragmented transit systems, and anti-growth attitudes will choke the boom times, the report says.

More doomsday scenarios to use as the basis for taking control of our government and everything associated with it.

The Bay Area may have 101 cities, "but it is one economy with more than 7 million people," says Bay Area Council President Jim Wunderman.

Telling that he left out the nine counties which are the dependent political subdivisions of our State.

"No city can perceive itself as an island. It's time for policymakers and business leaders to think and act with a regional perspective ... to maximize our many assets and keep the economy growing," he says.

All general statements that have no actual meaning, yet are used to advance this agenda.

The Bay Area Council is a business-sponsored public policy advocacy group.

The name for such a group in history is called fascism, corporatism, crony capitalism. This is undue influence on our government.

A key concept is the creation of a powerful regional government -- "a regional planning, finance and management" agency -- funded by tolls on bridges, highways and express lanes and a regional sales tax, gas tax, or vehicle license fee.

A key concept is turning taxpayers into rate payers, pricing drivers off their roads, limiting the public's right of way in their right of way and imposing a top down, Soviet style planned economy on the people. The toll money will likely be added to the transportation funding that is now supporting buying our land. It's about taking our land, our wealth, our freedom.

According to the study, the regional agency would develop "a stronger regional approach to addressing critical needs (of) infrastructure, housing, workforce training, and economic development."

This is a fundamental change in our form of government. There is no elected representative who can uphold their oath of office and participate in this regionalism.

(Late last month, an attempt to expand one regional agency's powers in this direction resulted in a pact to study merging the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments.)

MTC appears to have its roots in unconstitutional Congressional legislation from 1959 which consolidated all levels of government under the concept of "intergovernmental relations". The three levels of government (federal, state, county) were set up to operate independently from each other, as are the three branches (legislative, executive, judicial) within each of those levels of government. This regional, top down, one branch, specialty government is problematic in many ways. Government intervention into the operations of society needs to be reversed if we are to maintain anything but a totalitarian government.

Loss of local control, a new layer of government and more taxes are warning words for groups that monitor taxpayer burdens.

"Why do they need additional revenue?" asked Jon Coupal of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Foundation. "If some functions shift to a regional government, shouldn't the revenue stream follow?

Regional government is uncontrollable and no revenue should support such a government. This government needs to be absorbed into our State executive branch agency and Counties if we are to maintain a government that is accountable to we the people.

"California remains a very, very overtaxed state," he said. "It has the highest sales tax and highest gas tax ... and a great deal of mismanaged tax revenue."

Good point. Need to get some numbers to show this reality.

Tax increases might result in improvements, but much of the money will go to fund public employee pensions, he predicted.

Need to address pension crisis.

But he also sees a need to protect the area's economy. "Most of the major chip manufacturers have left California," he said. "A lot of high tech is moving to Denver and Salt Lake City, and a lot of biotech is moving to Salt Lake."

Companies move all the time. Others will take their place. There is nothing static about the economy. The problem is government policy that drives these companies out of our State. The government should not be put in the position of solving a problem it created.

Housing, a key to developing the workforce and easing commute strains, is in crisis: There's too little of it and it costs too much, the report finds. The Bay Area needs nearly 1.3 million housing units built by 2040 to meet demand, and there should be consequences when cities fail to meet state-mandated housing goals, such as loss of local authority to approve housing, the report advises.

This long term planning is used as justification that may or may not be correct or relevant. These generalities are also misleading. Developing the workforce is ominous use of technocratic language. The State does not need to mandate housing which supports sustainable development, a social engineering plan that limits freedom and choice of we the people. No one I know voted for this plan nor supports this ill conceived plan.

The plan includes the long-sought goal of easing environmental protection laws that hinder speedy construction or block building entirely.

This is a half truth. CEQA "streamlines" development that supports sustainable development and makes it more difficult to get environmental clearance for new development outside of urban centers. CEQA is another law that has been incrementally changed to support implementation of sustainable development.

"It shouldn't be read as the region vs. cities," said report co-author Micah Weinberg, a council senior policy adviser. "It should be 'How can we make it easier for cities to do the right thing by residents of the region?'"

What is the "right thing"? This is another generalized fallacy in that cities elect city council members who answer to we the people. The omission of Counties is very problematic in that Counties are part of our State. The idea seems to be to eliminate the States thereby eliminating the very reason our federal government exists so top down control can be expanded across our country and across the world.

Reducing construction costs would be packaged with quicker approvals for lower-cost construction and new building technologies, and capping fees throughout the region.

Coupal called the state's building permits and mandates absurd.

Well put.

The housing crisis is a "self-inflicted wound," he said. The report does not consider actions suggested by other factions in the Bay Area's growth debates, such as making businesses that rely on commuters help pay for their transportation and housing needs.

Well put.

That's a nonstarter for Weinberg and Wunderman.

"When you start to pick off individual businesses, it does not scale," Weinberg said. "You need the scale of a state or region to make the investment you need in transportation."

More general statements that have no meaning. We have a State transportation agency, we used to have a County transportation agency, now VTA.

Wunderman said the world economy is too dynamic to risk the Bay Area's momentum.

More general statements that have no meaning. Need to ask the who, what, where, when, why and how questions to get to the necessary specifics to advance the conversation.

"If you have jobs, you can solve problems. ... The last thing you want to do is put the brakes on the economy."

Yet more general statements that have no meaning.

Contact Andrew McGall at 925-945-4703. Follow him at twitter.com/AndrewMcGall

Economic resilience

"A Roadmap for Economic Resilience" sets six actions needed to sustain the Bay Area's economic growth and to prepare it for natural disasters.

Create a regional infrastructure financing authority with the power to play a stronger role in regional transportation finance and planning.

This gives authority for unlimited borrowing which obligates the public to pay debt that would then be supported by combining public money across all nine counties. The State has already passed many ill conceived bills that support borrowing that is not approved by the voters. Our elected representatives have a fiduciary duty to keep the taxpayers solvent whether they are driving or developing or anything else. This is irresponsible action that implements sustainable development.

Give the regional authority enhanced power to acquire funding.

Power, power, power, it's all about power.

Coordinate the building of large-scale water recycling, desalination, and storage infrastructure through a regional entity.

We have a State, we don't need regional agency to coordinate across counties.

Lower the voter threshold for county infrastructure taxes to 55 percent.

This is a way to take decision making out of the hands of voters. There is a reason for a high threshold for taking people's money. Need to explore other sources of money for support of public projects.

Establish a separate environmental review process for infrastructure.

Plan for resiliency in all infrastructure decisions (to prepare for and react to natural disasters)

The implementation of sustainable development appears to be included in every aspect of our society. This is a very dangerous situation.

The full report is online at www.bayareaeconomy.org

Bay Area needs powerful regional government to keep economy vibrant, study says

Bay Area needs powerful regional government to keep economy vibrant, study says

By Andrew McGallamcgall@bayareanewsgroup.com |

| The solution is more centralized government. What possibly could go wrong? |

The Bay Area generates one of the brightest sparks in the nation's recovering economy, but feeding its vitality means residents will have to give up some local control, dig deeper into their wallets, and make room for tens of thousands of new neighbors, according to study released Friday.

Keeping on prosperity's path requires a regional government with power to overcome local obstacles, money from new taxes and tolls, and opening the doors to housing closed by local growth controls and state environmental red tape, according to "A Roadmap for Economic Resilience," an in-depth study done by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

Without action, the Bay Area's highways choked with commuters, its fragmented transit systems, and anti-growth attitudes will choke the boom times, the report says.

The Bay Area may have 101 cities, "but it is one economy with more than 7 million people," says Bay Area Council President Jim Wunderman.

"No city can perceive itself as an island. It's time for policymakers and business leaders to think and act with a regional perspective ... to maximize our many assets and keep the economy growing," he says.

The Bay Area Council is a business-sponsored public policy advocacy group.

|

| Add caption |

According to the study, the regional agency would develop "a stronger regional approach to addressing critical needs (of) infrastructure, housing, workforce training, and economic development."

(Late last month, an attempt to expand one regional agency's powers in this direction resulted in a pact to study merging the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments.)

Loss of local control, a new layer of government and more taxes are warning words for groups that monitor taxpayer burdens.

"Why do they need additional revenue?" asked Jon Coupal of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Foundation. "If some functions shift to a regional government, shouldn't the revenue stream follow?

"California remains a very, very overtaxed state," he said. "It has the highest sales tax and highest gas tax ... and a great deal of mismanaged tax revenue."

Tax increases might result in improvements, but much of the money will go to fund public employee pensions, he predicted.

But he also sees a need to protect the area's economy. "Most of the major chip manufacturers have left California," he said. "A lot of high tech is moving to Denver and Salt Lake City, and a lot of biotech is moving to Salt Lake." Housing, a key to developing the workforce and easing commute strains, is in crisis: There's too little of it and it costs too much, the report finds. The Bay Area needs nearly 1.3 million housing units built by 2040 to meet demand, and there should be consequences when cities fail to meet state-mandated housing goals, such as loss of local authority to approve housing, the report advises.

The plan includes the long-sought goal of easing environmental protection laws that hinder speedy construction or block building entirely.

"It shouldn't be read as the region vs. cities," said report co-author Micah Weinberg, a council senior policy adviser. "It should be 'How can we make it easier for cities to do the right thing by residents of the region?'"

Reducing construction costs would be packaged with quicker approvals for lower-cost construction and new building technologies, and capping fees throughout the region.

Coupal called the state's building permits and mandates absurd.

The housing crisis is a "self-inflicted wound," he said. The report does not consider actions suggested by other factions in the Bay Area's growth debates, such as making businesses that rely on commuters help pay for their transportation and housing needs.

That's a nonstarter for Weinberg and Wunderman.

"When you start to pick off individual businesses, it does not scale," Weinberg said. "You need the scale of a state or region to make the investment you need in transportation."

Wunderman said the world economy is too dynamic to risk the Bay Area's momentum.

"If you have jobs, you can solve problems. ... The last thing you want to do is put the brakes on the economy."

Contact Andrew McGall at 925-945-4703. Follow him at twitter.com/AndrewMcGall

Economic resilience

"A Roadmap for Economic Resilience" sets six actions needed to sustain the Bay Area's economic growth and to prepare it for natural disasters.

- Create a regional infrastructure financing authority with the power to play a stronger role in regional transportation finance and planning.

- Give the regional authority enhanced power to acquire funding.

- Coordinate the building of large-scale water recycling, desalination, and storage infrastructure through a regional entity.

- Lower the voter threshold for county infrastructure taxes to 55 percent.

- Establish a separate environmental review process for infrastructure.

- Plan for resiliency in all infrastructure decisions (to prepare for and react to natural disasters)

The full report is online at www.bayareaeconomy.org

Friday, November 13, 2015

How commuters get railroaded by cities

How commuters get railroaded by cities

Home » Planning » How commuters get railroaded by cities

By Joel Kotkin…

With more than $10 billion already invested, and much more on the way, some now believe that Los Angeles and Southern California are on the way to becoming, in progressive blogger Matt Yglesias’ term, “the next great transit city.” But there’s also reality, something that rarely impinges on debates about public policy in these ideologically driven times.

Let’s start with the numbers. If L.A. is supposedly becoming a more transit-oriented city, as boosters already suggest, a higher portion of people should be taking buses and trains. Yet, Los Angeles County – with its dense urbanization and ideal weather for walking and taking transit – has seen its share of transit commuting decline, as has the region overall.

Since 1980, before the start of subway and light-rail construction, the percentage of Angelenos taking transit has actually dropped, from 7.0 percent to 6.9 percent, while the region (including the Inland Empire and Ventura County) has seen the transit share drop from 5.1 percent to 4.7 percent. These reductions in ridership have been experienced both on the rail and bus lines.

The simple truth is that this region is just not structured to run largely on rails. We should not prioritize our transit dollars on trying to remake our region into something resembling New York, or even San Francisco, but in serving the needs, first and foremost, of those who remain dependent on public transit.

History and Legacy

The primary reason transit does not do well in Los Angeles is historical. Although Southern California arose with a strong transit base – the Pacific Electric Red Cars and the Los Angeles Transit Lines Yellow Cars – that structure began fading by the 1920s as private car use surged in the region. It’s also critical to recognize that the vast majority of Southern California’s growth – roughly 75 percent – came after World War II and also after the demise of the Red Cars.

Since early in the region’s development, our business and residential patterns reflect the dominance of automobiles, with numerous economic nodes and residential districts spread out in largely suburban communities. In terms of overall settlement patterns, only 10 percent of the L.A.-Orange County region – generally the area south of the Santa Monica Mountains and the San Bernardino (I-10) Freeway, north of Slauson Avenue and between Fairfax Avenue and the Long Beach (I-710) Freeway – can actually be considered urban in the traditional sense, with higher densities and a higher market share of work trips by transit.

Downtown connection

Critically, Southern California lacks a magnetic center, with Downtown Los Angeles accounting for barely 3 percent of all employment in the region. As population and jobs continue to concentrate in the periphery, we should be wary of building a transit system to serve a geography to which relatively few commute. Downtown L.A. may have revived as a destination and residential area, but not as a job center.

Strong downtowns are what make rail transit work. All cities with successful transit systems, notably New York, have powerful, magnetic downtowns. Manhattan’s business district accounts for 20 percent of all jobs in the region, many times L.A.’s rate.

New York commuters may depart from a host of locations but head generally to Manhattan, a critical business center back when Los Angeles was little more than a glorified cow town. Cars came on the scene fairly late in the urban evolution.

But New York is not duplicable, so much so that roughly two-fifths of all U.S. train commuters live in the New York City region. Nearly 85 percent of all the transit ridership increase nationally the past decade has taken place there.

Although none comes close to equaling New York, there are several “legacy” cities that have larger-than-usual concentrations of employment in their central cores. These also include cities – Washington, D.C., Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago and San Francisco – that developed before the rise of the car, although not nearly to the extent of Gotham. Together, these places account for 55 percent of all transit work-trip destinations in the nation.

As for the remaining cities that have built extensive systems, it’s not a pretty picture. Even those systems that tend to get the widest praise and positive media coverage have had very limited success. Before opening its massive light-rail system in 1990, 4.3 percent of Denver’s commuters rode transit to work. With lightrail, the share did rise – to 4.4 percent.

Even Portland, Ore., considered the mecca of “smart growth” strategy, actually has seen a decrease in its transit market share, from 7.9 percent before light rail to 6.4 percent in 2013. San Diego, arguably with one of the more successful light-rail systems, has seen its transit market share stagnate, from 3.3 percent in 1980 – before light rail – to 3.2 percent in 2013.

All Southern California’s Sunbelt rivals have done poorly in terms of transit share. Atlanta, which built its subway earlier than most, has seen its transit market share cut by more than half.

Or, take the Dallas light-rail system – DART – which serves growing Dallas and Collin counties, an extensive area where just 2 percent of metropolitan area employment is downtown. DART expanded its lines by approximately three quarters from 2000-14, but still lost commuting market share.

The story is similar in Houston, where the light-rail system opened in 2004. From 2003-14, the population in Harris County, which includes Houston, grew 23 percent, but transit ridership decreased 12 percent, according to American Public Transportation Association data. This means that the average Houstonian took 30 percent fewer trips on the combined bus and light-rail system in 2014 than on the bus-only system in 2003.

Finally, in each of these cities, driving alone has increased, and all of them, most recently the Los Angeles region, now have more people working at home than riding transit to work. Commuting time is a big reason. Few transit trips in most cities take less time, door-to-door, than traveling by car, not to mention the convenience of working at home. The average transit rider in Los Angeles spends 48 minutes getting to work, compared with 27 minutes for people driving alone.

21st century transit

In the future, we need to focus on the people, largely poor, who should benefit most from transit investment. Transit commuters in the Los Angeles metropolitan area earn approximately 60 percent less than those in the six metropolitan areas with legacy cities.

These people should be the primary concern of transit agencies. But in the planning drive to re-engineer Southern California by building much more expensive rail systems, bus lines have been cut back, which also has occurred in many other cities embracing new train systems. As one former transit agency head recently explained, in confidence, this is part of a strategy to promote high-density real estate investment along transit routes. Trains, he explained, also can attract a more affluent rider, who could also easily drive to work.

Perhaps rather than trying to recreate the transit city of the early 20th century, planners should seek solutions that make sense in the dispersed environment of this century. Ideas that promote underinvestment in roads, supposedly to encourage transit use, are akin to inflicting cruel and unusual punishment on motorists. In Los Angeles, with the nation’s second-worst roads (the Bay Area is doing even worse), this translates to more than $1,000 in annual repair and maintenance costs per typical driver.

This cost particularly affects poorer populations, who tend to have older cars and have to steer through the most congested areas. L.A. Councilman Gil Cedillo, a longtime labor activist, made this point while objecting to Mayor Eric Garcetti’s gambit to expand bike lanes, reduce vehicle lanes and not invest in adding road capacity. Cedillo claims this “elitist” plan would hurt his constituents, few of whom would be using bike lanes to get to work, by assuring continual gridlock.

Rather than underspending in our road networks, perhaps more attention might be paid to making them work better for transit commuters. Rapid transit by bus could certainly be cheaper. But we also could explore using Uber-like door-to-door ride-booking services more often, with perhaps subsidies for poor riders. Such a step, or even buying cars for these low-end commuters, would greatly expand the range of jobs and locations available to them.

Further in the future, we might see the influence of autonomous, self-driving taxis and buses, which could be much cheaper, more reliable and less traffic-snarling than their current iterations.

Rather than commit our region to ever more expensive transit systems, we need to focus primarily on serving the transit-dependent population as efficiently as possible while looking to improve transportation outcomes on the vast majority of people who are likely to remain behind the wheel.

Joel Kotkin is the R.C. Hobbs Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University in Orange and executive director of the Houston-based Centerfor Opportunity Urbanism.

Wendell Cox, also a fellow at COU, is principal of Demographia, a St. Louis-based public policy firm, and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission.

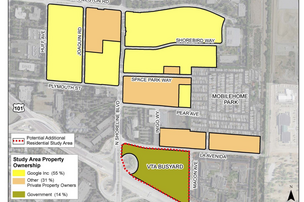

9,100 housing units next to Google? Mountain View council signals support for sweeping North Bayshore housing plans

9,100 housing units next to Google? Mountain View council signals support for sweeping North Bayshore housing plans

Nov 11, 2015, 5:29am PST UPDATED: Nov 11, 2015, 8:09am PST

All year, the Mountain View City Council has been preparing to add housing into the city’s North Bayshore business district. But the big question has been this: How many homes?

On Tuesday, a number finally started to come into focus — up to 9,100 units.

The council indicated its preference for a range of 6,700 to 9,100 units, which was the densest option in a slate of four development scenarios presented by city staff. The straw vote came during a study session as officials hashed out what kind of residential community they wanted to see develop in the North Bayshore, home to Google, LinkedIn, Intuit and Microsoft.

“It gives us the most flexibility moving forward,” Vice Mayor Pat Showalter said at the meeting, regarding the number of units. “It’s not all going to be built. So having more areas where it’s allowed is better.”

The decision doesn’t instantly allow that much housing in the North Bayshore, a 500-acre enclave cut off from the rest of the city by Highway 101. But it’s a critical step because it informs the environmental review that paves the way for updates to the area’s existing land-use guidelines and zoning. In essence, it sets the upper limit for what could be allowed in the district, though adoption of a revised plan remains many months away.

The meeting is a milestone in a story arc that has been among the most complicated Silicon Valley land-use sagas in recent memory.

A quick backstory: More than a year ago, a previous city council approved a plan for the North Bayshore that allowed up to 3.4 million square feet of net-new office space, but no housing. That stirred passions from housing advocates who said approving such massive job growth without adding nearby housing aggravated the Bay Area's commute patterns and encouraged suburban sprawl. (For its part, Google has long supported adding housing to North Bayshore.)

Voters agreed, and a pro-housing council majority was voted into office last November. In February, they began to study what it would take to add housing back into the plan. The answer: An update of the 2014 precise plan's environmental review, a complicated process that will take months.

The housing issue is essential, backers say, for getting the city’s out-of-whack jobs/housing balance back under control. The North Bayshore has become a major symbol of the imbalance, with hordes of tech workers commuting from all over the Bay Area into the district, clogging roads at peak travel times. Pro-housing advocates say that adding thousands of units will create a walkable community with life beyond the 9-to-5 workday, rather than what's now a soulless office park. (Currently, the only housing in North Bayshore is the Santiago Villa mobile home park, which has more than 350 households.)

It also may be critical for the expansion plans of Google, which is looking for ways to reduce traffic so that it can build ambitious office projects.

Under the existing precise plan, office development cannot occur if the district exceeds new automotive trip caps. Housing near jobs is believed to help the traffic issue, and Google suggests in a letter to the city that office capacity that’s freed up as a result of residential development should be credited to the builder of said residential project. (Since Google will likely build most of the housing in the area, it would see a direct benefit from such a policy by getting those development-rights transfers.)

Yet allowing housing brings with it a host of tricky questions, not only over how many units, but also where it should go, what it should look like, and what kind of services it would require — even how many bedrooms the units should have.

On Tuesday, council members supported a land-use plan that would allow — but not require — residential uses over 60 acres of land. Most of that land is owned by Google, which supports building housing in its backyard. But other land owners — including Peery-Arrillaga and Renault & Handley — are also in the mix, and it’s unclear how the council’s vision fits in with property owners’ individual business plans. Already, the city is processing a conceptual proposal from the Sobrato Organization that would add 370 units of housing and 400,000 square feet of office off Space Park Way.

“The key is to incentivize land owners to convert from office to residential,” said Cliff Chambers of the Mountain View Coalition for Responsible Planning, which supported the highest residential density possible.

The council also supported studying housing on the Valley Transportation Authority’s bus yard. Google is in talks with the VTA to either acquire or lease the 17-acre site, though the VTA would need to service its bus fleet somehow. In a letter to the city, Google reiterated its position in favor of housing there: “As part of a mixed-use site, we believe that the VTA Site is necessary to create the quantity of housing needed in North Bayshore,” wrote real estate executive Mark Golan.

A lot of homes

The unit count being contemplated is ambitious, and far exceeds previous numbers floated, most notably a number around 1,100 that had been studied in the original environmental impact report but later dropped from the plan by the former council.

The unit count being contemplated is ambitious, and far exceeds previous numbers floated, most notably a number around 1,100 that had been studied in the original environmental impact report but later dropped from the plan by the former council.

City staff considered that figure early on, but later set a minimum of 2,800 units in the scenarios presented to the council this week. "Eleven hundred units just wasn’t enough to create a substantial new neighborhood and also support, say, a local grocery store," said Martin Alkire, principal planner for the city, at the meeting. "As you get to 3,000 units, we felt that was a reasonable starting point at the low end."

If fully built out, the 9,100 units would be larger than all of the units constructed in North San Jose since the passage of the city’s transformational north San Jose plan, which allowed 8,000 units in an initial allocation that is now nearly drawn down. For instance, the massive north San Jose Irvine Company projects known as North Park and Crescent Village total about 4,950 units.

A staff report says that the 9,100 unit figure could produce up to 13,600 residents.

Yet it's notable that even though the unit range is large, it still lags the number of workers who will be added to the district in the years ahead — to say nothing of the existing employee base.

What gets built in Mountain View is likely to be much different in appearance than what's typical in suburban Silicon Valley cities. To make the most of the very compact opportunity sites, council members supported buildings that could rise 12 stories tall, a height that is rare for residential projects in Silicon Valley outside of downtown San Jose (and is even pretty rare there).

“If we want to mitigate some of the jobs housing imbalance, it’s going to require a greater number of 12-story buildings compared to five-story,” Chambers said at the meeting.

One issue the council wrestled with involved number of bedrooms. The environmental study supposes very few three-bedroom units, with most of them studios, one- and two-bedrooms. But Mayor John McAlister said he believes that projects should include three-bedroom units to support families. "Why are we discouraging families in this scenario?" he asked. But the council majority opted to go along with the smaller unit sizes, which would produce more housing.

What does Google think of all this?

While Google is an advocate for housing in the North Bayshore, the evolving zoning puts the search giant in an interesting spot. On the one hand, Google owns the majority of the land where housing could be built, giving Google control over what and when to build. On the other hand, that land is fully developed with offices, and Google already says it doesn't have enough office capacity in North Bayshore.

While much remains unclear regarding Google's plans for housing, the search giant did confirm on Tuesday that it would build affordable housing into any residential project it undertakes, rather than paying in-lieu affordable housing fees. Mountain View allows builders either to either designate 10 percent of their project as affordable or pay the fees. Integrating affordable housing into market-rate residential projects is considered a quicker and more efficient way to gain affordable units, though it is not required.

Google also said in a letter to city officials that it would not restrict its possible apartment projects to Google employees. "Rather, projects would be designed to encourage any North Bayshore worker to reside in order to accomplish traffic mitigation and help achieve a better jobs/housing balance in North Bayshore," Golan wrote to the city.

Nathan Donato-Weinstein covers commercial real estate and transportation for the Silicon Valley Business Journal.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)