California's Legal Assault On NIMBYs Begins

Over 100 bills aim to fix the state’s severe housing crisis, including many that would crack down on developers and communities that aren’t doing their part.

A California Department of Housing and Community Development report published earlier this year paints a dire picture: Home ownership rates are at their lowest numbers since the 1940s; homelessness is high. Existing homes cost far too much for low-income and even middle-income residents. But the report focuses most of its attention on the homes that don’t exist yet.

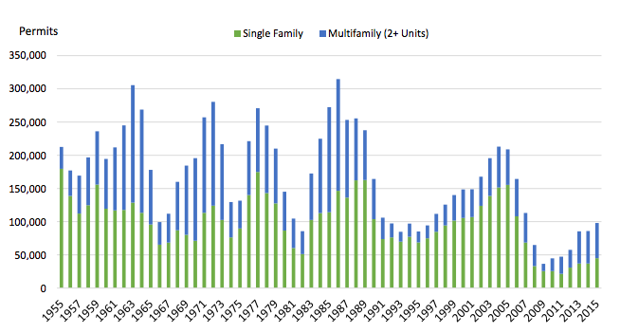

“In the last 10 years, California has built an average of 80,000 homes a year, far below the 180,000 homes needed a year to keep up with housing growth from 2015-2025,” the report says. “Without intervention, much of the population increase can be expected to occur further from job centers, high-performing schools, and transit, constraining opportunity for future generations.”

That latter bill epitomizes the frustration many young working people and families have as they try to attain what was once a milestone of adulthood—homeownership—that is now out of reach for even those making decent money. Some of those folks are YIMBYs, or supporters of a “Yes in My Backyard” agenda. “We know that our housing struggles are not the result of impersonal economic forces or lack of individual effort, but derive from bad policy and bad laws that have restricted housing growth for decades,” said YIMBY leader Brian Hanlon, co-founder of the California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund, at an April Assembly committee hearing.

California already has several laws on the books aimed at nudging localities to greenlight housing construction. One, the Housing Accountability Act, is even known as the Anti-NIMBY Act. But localities and residents have found ways around them. Many of the current proposals on the table either close loopholes opened by local governments, or add teeth to measures that some cities or neighborhoods have long ignored. A bill to strengthen the Housing Accountability Act, for instance, would even allow a court to authorize punitive damages against cities that act in bad faith. Another would set aside funds specifically for the state attorney general to enforce existing housing laws.

Democratic Assemblyman Richard Bloom, who represents several upscale Los Angeles neighborhoods including Santa Monica and Beverly Hills and who has written a package of housing bills, says many of the solutions that address localities aren’t meant to be antagonistic. “I think many in our local communities are very appreciative of clarifications. They recognize that things have gotten out of hand, and they’re not the right agencies to provide the clarity that we provide at the state level,” he says. “There are times, particularly in a time of crisis, that the state needs to step in and provide a better sense of expectations for local governments.”

Counterintuitively, some local officials might secretly crave punitive measures, says Dana Cuff, a professor of architecture and urban design and director of cityLAB-UCLA. “Because the most vocal and organized housing cohort is often a conservative one, city councils and local administrators have a hard time fulfilling their obligation in terms of providing more housing,” Cuff says. With state enforcement, she adds, “the local administrators will have a means to argue back that they have to do this or they will be punished.”

Other bills being floated, though, are more carrot than stick. One, written by San Diego Assemblyman Todd Gloria, would allow local housing authorities, which typically deal solely in affordable housing, to earmark some units in new projects for middle-income residents. Residents might be less likely to rally against a new project, the thinking goes, if it means their new neighbors will be teachers and firefighters in addition to those receiving housing subsidies.

During the recession, many market-rate projects that had been OK’d were abandoned by cash-strapped developers and converted into affordable housing projects because the government was the only entity doing any building. The community’s reception of a market-rate project compared with the same project when it became an affordable housing project was noticeably different, says Gloria, who was a San Diego city council member at the time.

“Whatever reason that might be, it could just be a pure no-growth approach or it could be a true fear of what affordable housing is perceived to be—and it’s never what it really is—maybe this [bill] is a way to address that,” he says.

It’s unclear what the chances for each bill are. Though legislators seem eager to spur more housing construction quickly, some of their allies might not be. Many environmentalists, for example, want new projects to comply with CEQA, the state’s landmark environmental law that requires developers to study and possibly mitigate the environmental impact of whatever they build. And developers are never quick to embrace mandates that they include affordable units in their projects.

If the bills do pass, will any of them actually make a dent in what’s become a crippling problem all across the state? The Sacramento Bee’s Dan Walters recently wrote off the current proposals in the Legislature as “tepid, marginal approaches that would do little to close the gap.” Cuff admits many critics dismiss individual bills as a drop in the bucket. “But on the other hand, let’s put a drop in the bucket,” she says. “A drop is better than a drought.”

Smaller, incremental solutions are also more likely to go over well with wary residents, as opposed to sweeping mandates that would never be implemented, Cuff says.

Bloom cautions that even if an explosion of housing production suddenly takes off, it will still take a long time for it to make a meaningful impact. Lawmakers also need to focus on solutions that can take the burden off of residents right away, he says, such as repealing certain restrictions on rent control.

“Even if I waved a magic wand today and we were to double our current housing production around the state, it would take us a minimum of 10 years to catch up,” he says. “I think that we need to give thought to the circumstances that tenants are facing today and see if there isn’t a way in which we can provide some immediate relief.”

No comments:

Post a Comment