When 'Gentrification' Is Really a Shift in Racial Boundaries

Jonathan Tannen has been tracking how neighborhoods change in the 100 largest U.S. cities, and what he discovered surprised him.

The diverse coalition of delegates who attended the Democratic National Convention last week may not have realized they were visiting one of the most segregated cities in the U.S. But even as a child growing up in a gentrifying, white enclave of West Philadelphia, Jonathan Tannen knew that people with his skin color rarely crossed 49th Street. It was the invisible line that separated his neighborhood from majority-black areas in the 1980s.

Two decades later, Tannen would spend six years at Princeton University working on a dissertation to quantify what he’d long suspected: that the invisible lines of segregation can be as real and hard as the bricks of any rowhome.“I wanted to see if I could measure lines between regions with very different racial characteristics,” he says.

Through his research he used a computer program to detect racial borders, like 49th Street, in the 100 largest U.S. cities. But along the way, he found something else that surprised him: As more suburban whites moved back to urban areas, old racial boundaries were moving, and spreading outward. But the neighborhoods themselves weren’t desegregating.

In fact, they were resegregating.

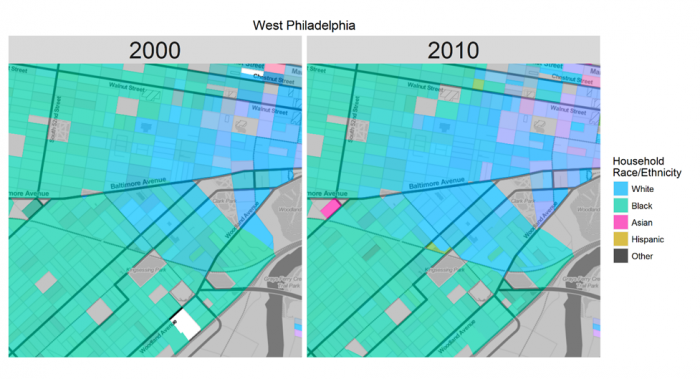

“You’re not seeing this historically black area becoming five percent white over ten years and then ten percent white. Instead, they went from almost 100 percent black to almost 100 percent white over ten years,” he says. “Philadelphia overall is becoming less white. But there are pockets of predominately white regions that are expanding. And the blocks along those boundaries are flipping very quickly, from a racial standpoint.”

Tannen arrived at these conclusions by feeding census data from 2000 to 2010 into what’s known as a Bayesian modeling system to see, essentially, if a computer could detect racial boundaries on its own. In his own neighborhood, the 49th Street boundary moved a full two blocks west between 2000 and 2010. Rather than desegregating, the formerly black blocks in between had become nearly all white.

Such findings about the nature of racial “boundary movements” could lead to some stark conclusions, especially in the context of the limited body of academic research into the processes behind neighborhood change.

“One of the arguments is that gentrification can’t be that bad if it serves to desegregate urban areas. And we have a lot of evidence that segregation is bad,” says Tannen, who today works as a researcher for Econsult, a Philadelphia-based analytics firm. “But if gentrification continues to happen by boundary movements, then that means the block level is never going to desegregate.”

The same boundary movements were present in the majority of the largest U.S. cities Tannen examined, including Chicago, New York, and Boston. But interestingly, and potentially uncomfortably for proponents of walkable urbanism, the phenomenon was only apparent in older, denser cities. In auto-centric cities, gentrification was more diffuse, and racial boundaries were less clear.

“Incoming white people in older cities are moving to areas that are around other white people. They’re saying ‘Oh, if I live here it’s somewhere I can afford, but it’s also close to [a bar] that I like.’ That process didn’t exist in places like Los Angeles.”

To be clear, his findings don’t suggest that gentrification is making segregation worse.

“Looking at racial data, it’s not that these gentrified regions are one hundred percent white, they’re actually very diverse for the country. So in some respects, looking at the country as a whole, the city looks less segregated,” he says. “You have 85-percent white clusters replacing 97-percent black clusters.”

Tannen acknowledges that his work is limited—it can’t quantify movements between a wealthy white neighborhood to an adjacent working-class white neighborhood. More importantly, it can’t say where the African-Americans who’d been living in these gentrifying neighborhoods are going or why they’re leaving.

“People start studying gentrification thinking they will be the ones to find the discrimination and the injustice in it. But these studies often end up complicating those ideas,” he says. “Displacement largely doesn’t happen.”

Recent research by the Pew Charitable Trusts confirms that the type of gentrification or neighborhood change described in Tannen’s work is actually rare. That study found that just 15 of Philadelphia’s 372 census tracts had gentrified over the same ten-year period. A Federal Reserve study, also focused on Philadelphia, indicated that displacement caused by gentrification is even rarer, and that non-gentrifying neighborhoods often lost existing residents even more rapidly than gentrifying areas.

Tannen says he thinks his findings are evidence that people are self-segregating, and it’s unclear what policy solutions could address that problem. Cities could start by being more mindful about the kinds of economic development projects they pursue along obvious racial borders, he says, due to their sensitivity to extreme racial change.

Ultimately, how cities can best tackle issues as thorny as segregation or displacement will not be solved by a single study. But Tannen’s research does at least answer, in part, why gentrification can feel like a big deal to residents even while it is also relatively uncommon.

“My work speaks to why that disconnect exists. Why can it feel to residents of cities that gentrification is real and it is extreme, even as the Pew study is correct in showing that the city as a whole is less white? How can those both be true?” he asks. “The boundary movements are an important part of that story—that gentrification is extreme to very small parts of the city. And where it happens, it happens very sharply.”

No comments:

Post a Comment