Most Wanted: San Francisco flyers name and shame Airbnb hosts

Posters in the city’s Chinatown claim Airbnb landlords are ‘destroying affordable housing for immigrant, minority and low income families’

Flyers in San Francisco’s Chinatown feature the names and photographs of individuals accused of ‘Airbnb’ing our community’. Photograph: Courtesy of Patrick Connors

Flyers in San Francisco’s Chinatown feature the names and photographs of individuals accused of ‘Airbnb’ing our community’. Photograph: Courtesy of Patrick ConnorsJulia Carrie Wong in San Francisco

@juliacarriew

Friday 22 July 2016 06.00 EDTLast modified on Friday 22 July 201613.29 EDT

San Francisco’s gentrification wars have long fostered a certain element willing to make the debate over affordable housing extremely personal.

During the first dot-com boom, members of the “Mission Yuppie Eradication Project” posted flyers encouraging residents of the once working-class Latino neighborhood to “vandalize yuppie cars”. During the current tech boom, asevictions soared, activists began using stencils to paint the sidewalks in front of certain buildings with an image of a suitcase and a message: “Tenants here forced out.”

‘Tech tax’: San Francisco mulls plan for taxing the rich to house the poor

But throughout all the turmoil, San Francisco’s Chinatown – 24 crowded blocks that have endured as a point of entry for generations of low-income Chinese immigrants – has remained largely insulated from the rancor.

Until now.

In recent weeks, “Wanted” flyers have been posted around the neighborhood featuring the names and photographs of 12 individuals. The crime in question? “Airbnb’ing our community” and “destroying affordable housing for immigrant, minority, & low income families.”

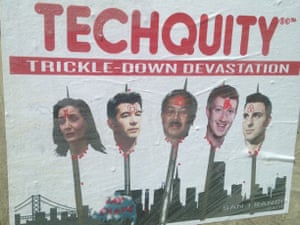

Unlike a flyer posted recently in the Mission District that featured the heads of various tech CEOs, including Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky, impaled on spikes, the Chinatown flyer names and shames individual Airbnb hosts.

FacebookTwitterPinterest A poster in the Mission district of San Francisco takes aim at big tech CEOs. Photograph: Julia Carrie Wong for the Guardian

“It expresses a growing sentiment and a reality that the community is being exploited by speculators and unscrupulous players in the housing market,” said city supervisor Aaron Peskin, who represents the district that includes Chinatown.

“There’s no question that there are an increasing amount of illegal short-term rentals throughout the city and in Chinatown.”

Indeed, Peskin said that just two weeks ago, he observed three French people leaving a Chinatown apartment building at 10am, rolling suitcases in tow.

‘Like a village’

The fact that a group of tourists staying in a residential building in the city that is home to Airbnb seemed remarkable is indicative of how insulated Chinatown has been from the market forces rocking the rest of the city.

“Chinatown has generally been preserved and defended against gentrification,” said Joyce Lam of the Chinese Progressive Association, a group that organizes workers and tenants in the neighborhood.

FacebookTwitterPinterest The Chinatown ‘Wanted’ poster. Photograph: Courtesy of Patrick Connors

Strict zoning laws enacted during the 1980s have protected the stock of single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels, which serve as low cost housing for newly arrived immigrants, as well as many elderly Chinese Americans. With their shared kitchens and bathrooms, Lam said the SROs can feel “like a village” to the multi-generation families crowded into single rooms.

But units that once changed hands solely through word of mouth or Chinese language flyers posted on the street are now popping up on Craigslist, Airbnb, and other short-term rental sites, as landlords have realized that they can earn more money renting to college graduates, single adults and white people, Lam said.

“It’s changed the fabric of the SROs,” Lam said, especially since the new residents often cannot communicate with Cantonese-speaking tenants. “It’s a different kind of feeling.”

The average rent of SRO rooms has increased as well, from $610 in 2013, to $970 in 2015, according to a survey conducted by the Chinatown Community Development Center. Those figures are enticingly low in a city where theaverage rent was $3,907 as of June, but increasingly unaffordable for many low-income immigrant families.

“Contrary to the posters, we don’t see the problem as being individual players,” Lam said, adding that her organization supports citywide reform legislation aimed at strengthening short-term rental regulation.

“We are more interested in having a meaningful discussion about San Francisco’s longstanding housing issues than responding to anonymous attacks on individual San Franciscans,” a spokesperson for Airbnb said in a statement.

The people on the poster

The appeal of Chinatown to non-traditional residents is described on Airbnb’s website, where a number of Chinatown listings feature photographs of the neighborhood’s famous Dragon Gate and paper lanterns.

“Cramped. Crowded. Dingy. Delightful,” reads the caption on Airbnb’s neighborhood description of Chinatown.

One Airbnb host who lists four rentals in Chinatown defended his preference for tourists over tenants.

“We rather leave rooms and apartment empty rather than renting because of rent control,” the host wrote to the Guardian. “Once tenants move in they own the property ... they have more rights than property owners.”

That host was not featured on the “Wanted” poster. None of the people on the “Wanted” poster who currently have Chinatown units listed on Airbnb responded to queries.

Justin Hobbs, who is on the poster, said: “I’ve seen this flyer and have reported it to AirBnB and will be filing a police report. If I’m able to find the creator of the flyer, there will also be a lawsuit filed for slander as this is completely untrue.”

Hobbs said that he lives in Nob Hill, not Chinatown, and he does not rent out his apartment, which is his only residence.

Another one of the people on the poster, who asked not to be identified, was also frustrated by it. The individual said that he no longer lives in San Francisco, but had used Airbnb once, several years ago, and has long since deactivated his account.

“I don’t see that what I did was criminal,” he said. “The reason why I left San Francisco is because it was way over gentrified and it was impossible to live as an artist, and now to get blamed as a gentrifier is just funny.”

Jeff Chen, who was also featured on the poster, was more sanguine about being singled out. Chen, who moved to a different part of the city in May, said that he rented his apartment a few times on Airbnb last summer, when he was traveling for work.

“I don’t really feel good about it [the poster], but I can see why members of the community are concerned about the housing situation,” Chen said. “I see stories about people who do [Airbnb] as a business, and I can see how that would drive up housing costs … I actually do identify with those concerns.”

No comments:

Post a Comment