How George Lucas’ bid for a Presidio museum misfired

By John KingApril 29, 2015 Updated: April 29, 2015 8:16pm

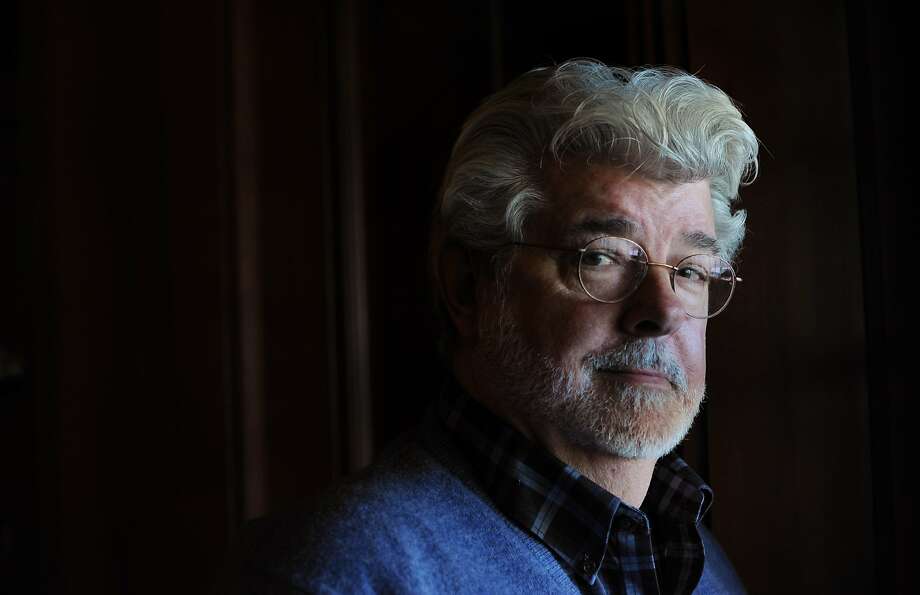

Photo: Erik Castro, Special To The Chronicle

Filmmaker George Lucas tried for three years to build a museum for his collection of digital and populist art before the plan combusted.

IMAGE 1 OF 5

Filmmaker George Lucas tried for three years to build a museum for his collection of digital and populist art before the plan combusted.

When the Presidio Trust announced last year that it was rejecting George Lucas’ bid to build a museum at Crissy Field, its leaders didn’t reveal that three days earlier they had been prepared to grant the “Star Wars” creator the land he sought.

Three members of the trust’s board of directors had met with Lucas at his office on Jan. 31, 2014, and the talking points prepared for them by Executive Director Craig Middleton included an offer to Lucas of “exclusive negotiations” for the 8 acres facing the bay if he agreed to change the look of his desired museum, a mock-classical temple that at one point had four ceremonial domes.

That revelation is among the previously undisclosed details of the strained relationship between the trust and the billionaire filmmaker found in several thousand pages of documents released to Lucas supporters this week in response to a Freedom of Information Act request signed by such luminaries as football legend Joe Montana, Twitter founder Biz Stone and Ron Conway, a venture capitalist with close ties to Mayor Ed Lee. The Presidio Trust also provided the documents to The Chronicle.

RELATED

George Lucas proposal out of place in Presidio

George Lucas proposal out of place in Presidio Major players in standoff over Crissy Field's future

Major players in standoff over Crissy Field's future Presidio Trust shoots down George Lucas' plan, 2 others

Presidio Trust shoots down George Lucas' plan, 2 others Chicago beats out S.F. for George Lucas' museum

Chicago beats out S.F. for George Lucas' museumInstead, Lucas rejected the offer. He complained about how he had been treated by the trust during his three-year quest to build a home for his collection of digital and populist art. On Feb. 3, 2014, the trust formally ended the competition, and five months later, Lucas was bound for Chicago.

Lucas first approached the trust “early in 2010,” according to an in-house review toward the end of the Crissy Field competition done for Middleton by senior staffer Tia Lombardi.

The land he sought was covered by a parking lot and a former commissary. It sits across from the marsh at Crissy Field, one of San Francisco’s most popular open spaces, with drop-dead views of the Marin Headlands and the Golden Gate Bridge. It also had been identified as a potential museum site as far back as the 2002 master plan for the Presidio, a 1,491-acre enclave within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

The initial design presented by Lucas is not part of the public record. But Lombardi’s later report described it as “very similar to the one in his final proposal. Some board members expressed tremendous enthusiasm, some were more ambivalent and some were perplexed.”

Instead of giving Lucas a yes or no, the trust waited until November 2012 before announcing a “request for concept proposals” with a March 1, 2013, deadline. During that time, the trust completed its design guidelines for the site while telling the Lucas team “two things,” Lombardi wrote: “that the building was not suitable for the site and that the trust would undertake a public process before determining the site’s use.”

That process brought proposals from 16 teams, but the only one that attracted national attention was the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. On display would be everything from comic books to animation cels, along with work by such popular 20th century illustrators as Norman Rockwell. Children and families would be welcome, Lucas told interviewers, and he would pay for the museum’s construction and endowment himself.

Even at this stage, the documents released this week show, there was a deep skepticism toward Lucas from Lombardi, the trust’s director of cultural affairs, and the consultant hired to help manage the process — Brent Glass, former director of the National Museum of American History.

In the months before the first deadline, they made overtures to a range of cultural institutions, including the de Young Museum and the National Building Museum. Lombardi also reached out to the local architecture firm WRNS Studio, which had worked for Gap founder Don Fisher duringhis unsuccessful bid to add a museum to the Presidio’s historic Main Post, characterizing them in an e-mail to Glass as “big thinkers.”

By contrast, Glass described Lucas’ concept in an e-mail to Lombardi as “the Empire meets Middle America.” To which Lombardi responded: “Or, Empire meets GWTW (“Gone With the Wind”) meets Middle America.”

Three finalists were announced at the end of April: Lucas, a team headed by WRNS and another one put together by the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, a nonprofit with a track record in fundraising and restoration efforts at the Presidio. All three were given until September to submit full designs and operational plans.

The months that followed included public open houses as well as choreographed campaigns of support on behalf of both Lucas and the Conservancy. Behind the scenes, though, tensions were high.

“Too bad that they use big clubs and we are slow to duck,” Lombardi wrote Glass in June, apparently referring to the Lucas PR campaign, which included endorsements by everyone from Lee to fellow filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola.

As for Lucas’ affection for the work of Rockwell, best known for his atmospheric Saturday Evening Post illustrations: “He was a brand. But a force? I don’t think so,” opined Lombardi, who no longer is with the trust. “In fact, who cares about Rockwell?”

Glass was even more scornful. In one exchange with Lombardi, he paired a Lucas quote dismissive of contemporary art with a quote from Adolf Hitler regarding “artworks that cannot be understood in and of themselves.”

Glass’ commentary: “75 years, ve have come full circle.”

In July, Middleton sent out a memo with the subject header “Remaining above the fray” to Lombardi and the trust’s top planner, Michael Boland.

“Hey team, allegations/rumors about our lack of objectivity regarding the 3 contenders persists,” Middleton warned. “I have no doubt about the integrity of our team and our process. ... We just need to be sure that nothing we say or do could provide even the slightest bit of fuel to these rumors.”

The now-public documents give no indication that the trust’s board of directors — six appointed by President Barack Obama, one by the U.S. secretary of the interior — knew of, or were influenced by, derogatory comments about the Lucas bid at staff level. Instead, e-mails among board members during 2013 and early 2014 show a desire to make room for Lucas without letting him call the shots, and frustration at his perceived unwillingness to meet them halfway.

The board’s chairwoman, Nancy Hellman Bechtle, in March of 2013 described the Lucas concept proposal as “very good.” But six weeks later, referring to “what George Lucas said, he wants a yes or a no,” she asked other directors, “Should we in some manner tell Lucas that a building that resembles the Palace of Fine Arts is not acceptable? That (the permissible) height is what is in the design guidelines?”

Another board member, developer Alex Mehran, initially gave his highest ranking to Lucas’ proposal. But in May he wrote that even though Lucas should be one of the three suitors asked to submit a full proposal, “the architecture needs to be addressed. Are they willing to seek expert architectural input?”

The design packets that arrived on Sept. 10 brought the tensions to a head: Lucas submitted a Beaux-Arts complex festooned with eclectic ornamentation, including copper domes and arches that rested on columns adorned with robed figures. Its stated inspiration was the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition that spawned the Palace of Fine Arts, and accompanying text declared, “The Lucas Cultural Arts Museum believes its chosen architectural vocabulary is worthy of the site.”

The Lucas proposal also exceeded the site’s 45-foot height limit by more than 20 feet. But as the trust attempted to do a set of simulations showing how each finalist would alter the views from various perspectives, the Lucas team disputed the accuracy of the results for much of the fall.

As the mid-November target date for a board decision neared, Middleton and Boland met with Lucas’ architects and the filmmaker’s project manager, Angelo Garcia. Middleton’s report back to the board was glum: “Neither Michael not I left the meeting feeling much optimism about their level of flexibility.” As for concerns about height and the classical design — at the board’s behest, Middleton and Boland had presented the Lucas team with images of contemporary buildings in traditional settings — Middleton wrote that Garcia had told him, “GL expects the museum to 'stand out.’”

Board members were hearing from the Lucas side as well.

The day after the meeting described by Middleton, Lucas attorney Mary Murphy sent a five-page memorandum to Mehran and Bechtle challenging the fairness of the view studies. She also objected to the idea that her client’s proposal might face legal obstacles because of the past agreements by the autonomous trust to run any major Presidio alterations by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

“We are concerned that the staff may be expressing a measure of alarm regarding the reaction of the consulting parties,” wrote Murphy, herself a former member of the trust’s board. “Although the Trust has an obligation to consult with other agencies ... the authority to approve the project rests with the Trust itself.”

That point was seconded by another Lucas supporter: Sen. Dianne Feinstein. “Those three agencies can only make recommendations,” Feinstein suggested in a letter to Bechtle after the two had lunch. “The final decision rests with you and the Presidio Trust Board.”

Even amid the flurry of comments flying in from supporters and opponents of the various teams, this advocacy from a U.S. senator stood out. “Do you think her interpretation of the approvals/consultation process is accurate?” one board member, Paula Collins, asked in an e-mail to the other six.

“I don’t know but we still have to get along with them,” was Bechtle’s response, referring to the other agencies. “Lawsuits by any would hold the project up forever.”

Pressure of another sort came from venture capitalist Conway. In November he sent a letter endorsing Lucas signed by dozens of leading figures in the world of high tech. He also spoke with Bechtle, following up with an e-mail: “All we want to do is encourage the parties to get to a constructive solution so it’s located in the Presidio and I know you are working on that per our chat.”

Two minutes later came Bechtle’s reply: “I’m doing my best, but compromises need to be made. As I said, if we lose it, it won’t be for lack of trying.”

Later that month the board sent all three teams back to the drawing board, announcing that it would delay a decision until 2014. Lucas was praised in the board’s statement for his desire “to draw diverse audiences to the museum and the greater Presidio.” But the statement added, “We have significant issues with the proposed building ... and believe it should be redesigned to be more compatible with the Presidio.”

On Jan. 17, the date set by the trust, the three teams sent in their revised proposals. Lucas’ included a one-story version — scoffed at in an e-mail from Lombardi to Glass as “the Never-ending (nightmare of a) Building scheme” — and a tweaked two-story structure with fewer decorations and a bit less height.

Despite the relatively minor changes, the appeal of having Lucas’ museum in the Presidio was strong enough that he appears to have been the only finalist who was offered the commissary site — provisionally — before the competition was suspended on Feb. 3.

Three board members, including Mehran and Collins, met with Lucas on Jan. 31. They were accompanied by Middleton, who that morning sent them a set of points that they might want to make. His notes accentuated the positive (“We think the program you are conceiving holds great promise”) but also called the design a “make/break issue.” It needed to be in a different architectural style, “light on the land, and fully integrated with the park improvements around it.”

Lucas’ reaction can be gauged by the e-mails between board members after what one, Mehran, called “a long and disappointing meeting.”

“I keep replaying yesterday’s meeting to see if there were any other points we could have conceded and I can think of none,” Collins wrote. “Craig, you get the Zen award for calmly deflecting all those comments about staff.”

Middleton responded in kind: “You were all great. I don’t think I added much other than allowing him to have someone to vent about.”

Mehran’s verdict? “I think we should prepare for a no go w Lucas release.”

The final encounter between the trust and Lucas occurred on June 25 — the day after Chicago media broke the news that Lucas was accepting an invitation from Mayor Rahm Emanuel to build his museum on the shores of Lake Michigan.

“Met with George today — he wanted to tell us in person,” Middleton said in a note that afternoon to Bechtle, who had not been invited. “We agreed not to talk about the meeting; we left the door open should he ever want to engage again about something in the Presidio, and wished him well.”

The one letter from Lucas in this week’s batch of documents is dated Sept. 18, 2013, shortly after he was quoted in the New York Times as complaining that the trust was “having us do as much work as we can hoping that we will give up ... they hate us.”

Lucas’ Sept. 18 letter was delivered by messenger to Bechtle: “As you know, I feel passionately about the Presidio. When the NY Times reporter called, I intended to talk about how art had impacted my life and why I thought the Presidio was the perfect home for the museum, but when asked about the application process I’m afraid my frustrations got the best of me.”

Bechtle forwarded the short note to other board members.

“Is there an apology in there somewhere?” was Collins’ response.

“Yes, I think so,” Bechtle wrote. “Oblique perhaps but maybe the best he can do.”

No comments:

Post a Comment