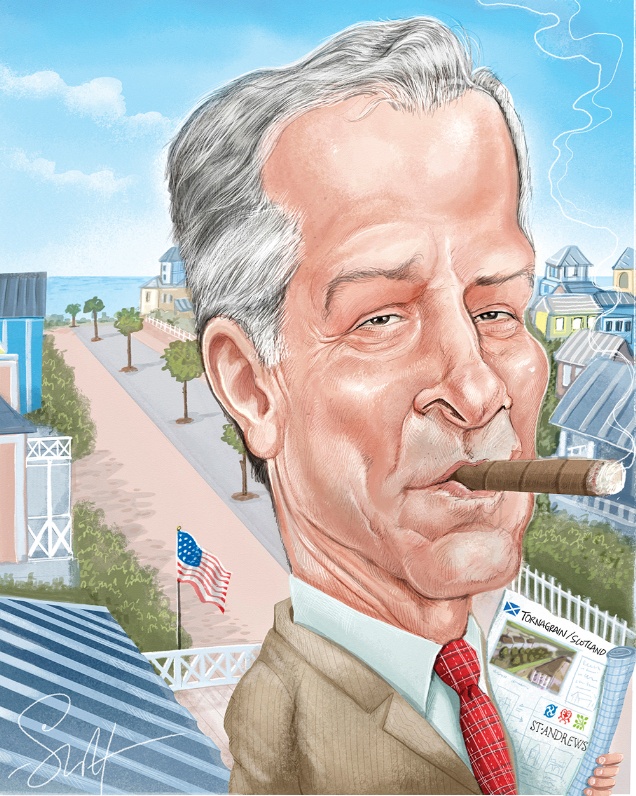

Source: Scott Clissold

Wearing tweed trousers, a tartan tie and a boyish air of can-do assurance, the architect and urbanist Andrés Duany was in London recently for one of his three annual visits to the offices of planning consultants Turnbury.

Duany’s Miami-based practice, DPZ — which he runs with his wife, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk — has become a regular collaborator with Turnbury over the past six years, providing the design input for a string of major developments in the UK. As the tie suggests, many lie in Scotland. The largest, Tornagrain, is soon to break ground on land near Inverness Airport and will ultimately house 10,000 people.

Co-founding the Miami-based Arquitectonica in the 1970s, Duany and Plater-Zyberk began their careers as architects. But for the past 30 years their interests have focused on the urban scale and in particular the lessons that historic towns might offer current development. Gaining international attention through their plan and design code for the neo-traditional Florida new town Seaside, they remain highly divisive figures.

And yet in Scotland, DPZ’s advocacy of coding has been received sympathetically, not least by the country’s recently retired chief planner, Jim McKinnon. Duany attributes this to the fact that Scots have an appetite for developing a planning culture to reflect their burgeoning independence. “When we arrived I could tell they had an attitude that they were becoming their own country,” he says. “McKinnon ultimately liked codes because they are rationalist. The Scottish enlightenment is not empirical. It’s a rationalist culture.”

Asking questions

As foreigners, he also felt the members of his practice were able to bring a fresh eye to the Scottish urban landscape and extrapolate lessons that could be applied to future developments. St Andrews, in particular, has served as a model for his schemes in the country.

“As Americans we were excited by what we saw,” he says. “We asked questions: What is a pend? What’s a wynd? How do you block the wind coming in from the sea? We asked questions the architects stopped asking.”

‘We’re not working with good designers but with builders. Acres of great architecture can be very oppressive’

Duany acknowledges that not all architects share his enthusiasm for design codes, but claims they offer more freedom than the traditional British system of planning by negotiation. “The idea that negotiating with an administrator is somehow a freedom, I find extremely obnoxious,” he argues. “I would rather deal with a rule than a person. That is a situation where I come in with rights.”

In the case of his three permitted Scottish projects, he is not expecting — nor even particularly hoping — that all the architecture will be of high quality. The likely outcome certainly sounds far removed from a project like Poundbury.

“Those were good designers working there,” he says. “We’re not working with good designers, we’re working with builders. I could design all the houses myself or I could get my buddies in but that’s not fair and it’s not urbanism. When you select the architects, you don’t need codes. It just becomes a large architectural project — and acres of great architecture can be very oppressive. There’s something that allows you to breathe when it’s not great architecture.”

Lessons from America

Duany is used to being attacked as a romantic but his arguments come rooted in pragmatic and even commercial concerns. Our conversation returns repeatedly to questions of affordability — a consideration that he believes should be given a much increased emphasis in discussions of urban form and sustainability.

He cites the development of America in the 1870s as a model for the kind of environment we should be seeking to create in our post-crash economy. With banks only lending in small increments and reluctant to extend loans on mixed-use buildings with complex leasing arrangements, he believes examples of urbanism from that period — such as the low-rise, small-grain grid of Portland, Oregon — have renewed relevance.

“The continent of the United States was colonised without a banking system from sheer common sense, management expertise and sequential design, and it created wealth. That technology, from the way it was managed to the way the bureaucracy ran — everything made sense. That 19th-century culture of engineering, married to a vernacular approach to delivering buildings — in the sense of thinking, not style — has a lot to teach us today.”

He argues that our current discussion of sustainability issues could also benefit from a dose of 19th-century common sense. He is particularly hostile to the demand for housing to incorporate hi-tech solutions. “Right now it is known that ecological design is more expensive, but it will pay for itself in the end, and I will not accept that,” he says. “Even passive technology is too expensive. I’d rather spend $500 on a beautiful curtain than triple glazing. The commitment to hi-tech is a commitment to cost — and we don’t have the money any more.”

Given that at Tornagrain the plan is to build 90 houses a year, Duany has no expectation of seeing the scheme completed in his lifetime. However, that is a situation with which he seems quite content. “As you become an urbanist you become a futurist. An architect finishes in five years; our Scottish projects may take 50 years to build out,” he says.

Slow as they may be to appear, it is a good bet that, like them or not, these projects will have a huge influence on future urban development in Scotland and beyond.

Three steps to new urbanism

Beginnings

Duany and Plater-Zyberk studied under Charles Moore at Yale before co-founding the Miami-based Arquitectonica in 1977. Their brand of mirror-plated pop modernism found fame through projects such as the Atlantis Condominium, which had a starring role in the opening credits of Miami Vice.

Discovering urbanism

A new engagement with urbanism followed their attendance at a lecture given by the young Leon Krier. “He was absolutely spectacular,” Duany recalls. “I thought Lenin must have been like this. And, of course, at first I reviled him. I spent two weeks in a yellow fury.”

Seaside

After founding DPZ in 1980, Duany and Plater-Zyberk planned the Florida new town Seaside, as an exemplar of the principles that came to be known as New Urbanism. The development prioritised pedestrian travel and directed the contributions of many architects — including Krier, Robert Stern and Steven Holl — through the application of design codes.

No comments:

Post a Comment