Levittown, on New York’s Long Island, new starter homes were plentiful in the late 40s and 50s. Click to visit the Instant House blog, a tribute to manufactured homes.

I had a depressing conversation recently with someone who does big housing construction deals for a big bank. There’s only two types of deals that work, he said. 1) Building pricey, premium granite countertop homes for well-off folks or 2) Building affordable housing with government subsidies. Roughly speaking: construction for the rich or the poor. Nothing in between.

Most important, nothing for that apartment-dwelling couple with a toddler and a baby on the way. That’s the lament I hear from all my urban friends around the country. Where can I start my family? Where is my starter home?

It’s gone. Builders and banks just can’t make money off humble homebuilding, or at least they think they can’t.

If he’s right, my banking friend solved a riddle that has been at the heart of The Restless Project: why do middle class folks feel so lost, even if they have decent jobs?

I set about trying to confirm my friend’s sentiment, and it was harder than I thought. There’s little agreement on what a starter home is. He blamed demanding millennials, who refuse to live in a house without granite. While that’s partly true, I think the problem is much deeper.

In fact, you could argue (and I will) that starter homes are basically disappearing. They aren’t being built and those that exist are either falling into functional disrepair (they are old), or more likely, being snapped up by investors to rent to young families.

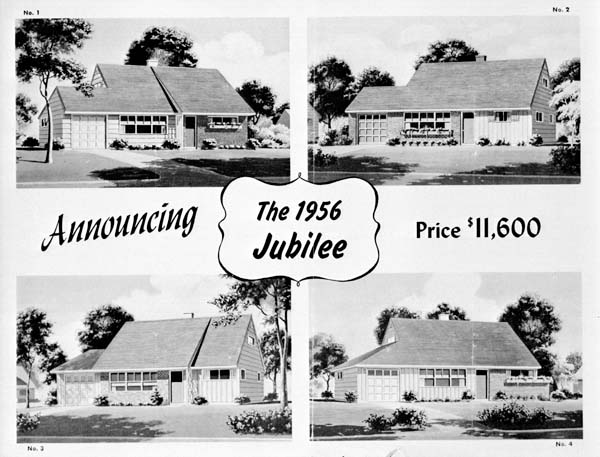

First, a little housing lesson. Back in the post-War boom, America’s housing industry was on fire. Single-family housing starts jumped an incredibly 400 percent during the decade. According to this great housing history, in 1950, the average price was $11,000. For perspective, median income, in real dollars, was about $3,300.

But here’s the number to watch: the average home was 963 square feet. A majority of homes had two bedrooms and one bathroom.

By 1972, prices had jumped to $30,000 while family income was nearly $10,000. Homes, which typically had three bedrooms and at least a bath and a half, now averaged 1,600 square feet. That kind of house can pretty comfortably shelter a family with 2.3 children.

Today, families are smaller — from 1970 to 2014, family size shrunk by about half a person. What’s the average square footage of a home? About 2,500. More space, fewer people.

That’s progress, of course. Now homes have central air and finished basements and man caves and spa tubs and yes, granite countertops. But all those things are useless to young families who have no idea where to find the $500,000 they have to pay to live in a place with decent schools that’s within 50 miles of their workplace.

A healthy housing market would provide a wide spectrum of housing – the $200,000 tiny place, the $400,00 step-up home, the $700,000 dream home. I promise you that plenty of my apartment-dwelling friends would love a two-bedroom starter home on a cozy lot. But they don’t seem to exist. Why?

This BuilderOnline.com story, “Are new starter homes history,” offers a tidy explanation. For now, let’s peg $200,000 as a starter home price. (For a fun fact, $30,000 in 1970 has the spending power of $185,000 today. But I’m going with round numbers). It begins with a tale I’ve told in other places — if a builder can construct homes that cost 2.5 times median household income in a neighborhood, the homes will sell like hotcakes. Two-and-a-half times? Median household income is roughly $50,000 in America today. See a lot of $125,000 homes sprouting up?

No. You don’t even see $200,000 homes sprouting up. In fact, only 46,000 new sub-$200,000 new homes were sold in 2014. Anywhere.

And here’s why, according to BuilderOnline.

Making a $200,000 home work as a home builder is junior-high–level arithmetic. Solving for profit—say, 20%—land and building direct costs can not exceed $160,000. Problem is, a 20% margin on a sub-$200,000 house has become frighteningly elusive in the past decade.

The lowest build cost is around a $50 a foot,” says David Goldberg, a home building and building products manufacturers analyst for UBS, New York. “If you do a 2,000-square-foot house, which is what you’d have to do to compete with existing stock, that leaves you with $100,000 of sticks-and-bricks cost. The maximum cost on the land would be $60,000.”

The catch to all this is that it’s not just one problem. No single culprit is killing the new starter home. A stream of factors—land, operational risk, labor, material costs, entitlement fees—converge at a single, all-too-real vanishing point where affordability becomes unaffordability.

Even if land can be secured at a reasonable cost, cash-thirsty localities heap fees upon fees that weigh more and more heavily on final home price tags. Chris Cates, co-owner of Fayetteville, N.C.–based Caviness & Cates Communities, estimates that regulations that stipulate he has to convert stormwater ponds to permanent ponds and bond items such as street lights, sidewalks, landscaping, and retention ponds have doubled his development costs.

So the numbers just don’t work. But left unsaid in another obvious factor, typical in all industries — every business strives to sell premium, high-margin goods. Your coffee shop wants to sell you pour-over brews at twice the price. You bar wants you to buy microbrews. Your car dealer wants you to buy an Ford Escalade, not a Ford Focus. The low end of the market is for suckers, or Walmart. At least until demand becomes overwhelming in that segment. But even then…housing isn’t like hamburgers. Even if builders today decided America needed 5 million new mid-range affordable homes, it would take years for projects to take shape, get approvals, get financing, etc. Housing is very slow to react to demand.

But that’s why there’s “used” homes, right? Young families are supposed to buy a needs-TLC place in their 20s, fix it up, and trade up to their dream home later.

The problem is cheaper, older starter homes are nearly as hard to find. Here’s one piece of evidence: The folks at RealtyTrac ran the numbers for me, and it turns out that year-to-date sales of sub-$200,000 homes is down this year compared to the last three years. That’s strange, given that sales above $200,000 are up. For example, two years ago, there were 395,000 sub $200,000 homes sold from January to May. This year, there were only 343,000. Rising prices can’t account for more than a fraction of that drop.

Worse yet, families who would buy cheaper homes are being edged out by investors who buy the homes and rent them out. Non-occupant buyers of single-family homes hit a record last quarter, according to RealtyTrac.

Worst of all — that’s even more true in hot, affordable communities where families are fleeing to avoid NYC and San Francisco prices.

Among metropolitan statistical areas with a population of at least 500,000, Memphis, Tennessee posted the highest share of institutional investor purchases of single family homes in the first quarter of 2015 — 14.1 percent — followed by Charlotte, North Carolina (12.1 percent), Atlanta, Georgia (9.6 percent), Jacksonville, Florida (8.5 percent) and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (7.6 percent).

Of course investors are buying in those places. At a time when it’s very hard to make money by saving, and the stock market appears fragile, renting to stable families is a great way to make return on investment.

Housing expert and loan officer Logan Mohtashami talks about the “cracked equilibrium” that has led to this state of affairs. Dual income parents with decent jobs shut out of the housing market because there’s just nothing but luxury homes to buy, trying to stick it out in their one-bedroom apartment. I keep saying that average people with average jobs can’t afford average homes in America, and that’s the source of untold strife.

There’s no law of nature that says buying a home is superior to renting one. There are plenty of logical reasons that young folks might choose to rent instead of buy, and more power to them. It’s been good for America to shed the idea that housing is a guaranteed investment / retirement plan. But Mohtashami warns about the potential long-lasting social consequences of an all-renter / landlord society.

“Are we at the beginning of a sociological movement away from middle class home ownership and towards a cultural split between the investment property landlords and their renters both of whom may have less personal investment in neighborhood security, local schools and shared public facilities compared to primary homeowners?”

Buying has one huge advantage over renting — fixed monthly payments. In all but the most unusual situation, that means housing really becomes cheaper as time passes, thanks to inflation. That is not true of renting, and certainly not now. Rents are rising at record rates around the country.

That puts families who want a place to live between a rock and….no place, really.

No comments:

Post a Comment