A blog about Marinwood-Lucas Valley and the Marin Housing Element, politics, economics and social policy. The MOST DANGEROUS BLOG in Marinwood-Lucas Valley.

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

Marinwood Pool Damage Discussion Nov 10, 2020

Wednesday, November 4, 2020

Wednesday, October 28, 2020

Wednesday, October 21, 2020

How Next-Door Neighbors With Opposing Political Views Stayed Friends

How Next-Door Neighbors With Opposing Political Views Stayed Friends

Troubled by the national discourse, the Gateses and Mitchells use signs to ‘send a message’ of civilityThe Mitchell and Gates families, longtime next door neighbors, don’t let politics interfere with their close friendship.

By

Clare Ansberry | Photographs by Ross Mantle for The Wall Street JournalOct. 20, 2020 12:08 pm ET

The Mitchells, lifelong Democrats, planted a Joe Biden sign in the front yard of their suburban Pittsburgh home. The Gateses, who live next door and are lifelong Republicans, put a Donald Trump sign in theirs.

Another homemade sign stands in each yard. It reads: “We (Heart) Them” with an arrow pointing to the other house. In the middle of each heart are the words “One Nation.”

“There’s so much hate,” says Chris Senko Mitchell, who came up with the idea. “We want to send a message.” The message, say members of the Mitchell-Gates households, is this: People on opposite ends of the political spectrum can actually like each other and be civil.

The question, for many people, is how.

Signs with arrows, reading ‘We (Heart) Them,’ stand alongside opposing political signs in the Mitchell and Gates front yards in Mt. Lebanon, a suburb of Pittsburgh.

Millions of Americans are alarmed at the bitter split in the country, with 9 out of 10 Americans saying incivility is a problem and two-thirds saying it’s a “major” problem—according to a 2019 poll by public relations firm Weber Shandwick taken before this year’s tumultuous events.

“People know how wrong this division is and actually want out of it, but they don’t know what to do,” says Carolyn Lukensmeyer, former executive director of the National Institute for Civil Discourse at the University of Arizona. The institute, which describes itself as a nonpartisan organization set up to promote healthy and civil political debate, offers programs on getting along despite differences.

People can start by listening attentively and with an open mind, says Dr. Lukensmeyer. Too often, people interrupt others or mentally prepare rebuttals while another person is talking.

“Listen long enough to understand how that human being came to hold the view they hold. If someone says something you don’t believe is factual, don’t respond in conflict or try to convince them otherwise,” she says.

The Mitchells—Stuart and Chris—and the Gateses—Bart and Jill—met 14 years ago on their suburban street in Mt. Lebanon, Pa., and quickly bonded. Each couple has three children, roughly the same ages, who often walk to their neighborhood schools together and swim in the Mitchell backyard pool. The families share a love for hockey, the boys playing on the same team and the dads serving on the high school hockey board. When the Pittsburgh Penguins play in the NHL playoffs, Stuart sets up a big screen and projector in his driveway, and the families gather with others to watch.

“Our lives are intertwined,” says Stuart. “We call each other family.”

From left, Chris Senko Mitchell, Stuart Mitchell, Jill Gates and Bart Gates and their six children. They gather Monday evenings for dinner.

Although they generally don’t talk about politics, they know where each household stands. When Barack Obama ran for president, Stuart, who is biracial, put a floodlight on a big Obama poster hung on his porch. Both families joked about his “Obama shrine.”

“They are pretty far left and we are pretty far right,” says Jill.

So how do they get along?

They don’t argue. They don’t label each other. They listen to each other’s perspective, look for common ground and recognize that reasonable and good people can reach different conclusions.

“I think it boils down to respect,” says Chris. “We have no desire or illusion that we are going to change them or each other’s minds.”

They also rarely bring up issues that are more divisive than others, like abortion.

The subject came up only once, soon after Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died. The oldest boys, along with Bart and Chris, were in Virginia for a hockey tournament. Jill and Stuart were watching the game live-streamed at her house. After the game, they started talking about President Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barrett, her stand on abortion and efforts to have her approved before the election.

Jill, a Catholic, opposes abortion and supported the nominee.

Stuart, who was raised Methodist and grew up in Brooklyn, was familiar with a time not long before when abortions were illegal and performed dangerously in the streets and in bathrooms. “We are not coming from the same place,” says Stuart, who was also concerned about an unbalanced Supreme Court.

“He grew up in New York City and saw way more difficult situations than I was ever exposed to,” says Jill. “We listened, had our discussion. It was never heated and it was over.” The next morning, Stuart came over with his cup of coffee and they watched their boys’ next match.

From left, Bart Gates, Jill Gates and Stuart Mitchell talked in the Mitchell home on Monday.

The families also look for common ground. Stuart, a banker, and Bart, an accountant, often talk about the economy, its ills and ways to address them. “We have a lot of shared ideas about what is wrong and whose needs need to be addressed,” says Bart. “We differ on the best way to handle it.”

Both agree the country’s debt levels are too high, that more revenue is needed, but disagree on how much individuals and corporations should be taxed and where spending cuts should be made. They agree many Americans are struggling and need help, but don’t agree on what role the government should play.

The “heart” sign was prompted by a conversation over a weekly dinner together, a relatively new tradition they call Monday Mixer.

Last month, when school began remotely, the families, who had been in each other’s bubble since the pandemic hit, began eating together every Monday night, taking turns hosting and cooking for six children and four adults.

Do you have friends who support opposing candidates and how do you get along with them? Join the conversation below.

One recent Monday, Jill was hosting the Mitchell family. They talked about school, children, hockey, the delicious Chicken Alfredo and chocolate-chip cookies. The conversation turned to yard signs.

The Mitchells said someone stole their Biden sign.

The Trump sign was gone, too, but not stolen. Jill said she felt pressured to take it down when once-friendly people started walking past her without saying hello. “I was being shaded, and I knew it was because of my Trump sign,” says Jill.

The more they talked that evening, the more disappointed and upset they became about the growing hostility nationally and locally, and the impact it could have on their own children.

“I’m going to make a sign,” Chris recalls saying, one that showed they loved their Trump-supporting neighbors. Jill said she wanted to make one, too, declaring affection for their Biden-supporting neighbors.

Along with making a public statement, they wanted to show their children that people can choose to get along despite their differences. “Our fundamental job as parents is to be a good role model for our children,” says Bart. ”We don’t see them as Democrats. They’re the Mitchells. We know they are good people who live next door. We love them.”

Good signs make good neighbors: the Mitchell front yard, left, and the Gates home, right.

At first, their teenagers were mortified. “They came home and said, ‘Oh my God, Mom. What the heck is this?’” says Chris.

Now Gillian, her 14-year-old daughter, doesn’t mind. “I’m not a voter, but I think people should be mature and not argue all the time or fight. Fighting just leads to more fighting.”

The couples say they haven’t had any backlash from their handmade signs. Stuart says he receives texts from people about work or hockey. At the end, they text “BTW, I love your sign and the Gateses’.”

Advice From the Mitchell and Gates Families

Stuart: Accept that you don’t have to be right. I thought I was right all the time growing up. If you don’t think you have to be right, you listen more.

Chris: Treat others the way you want to be treated.

Bart: Recognize that the other person deserves respect. Be willing to consider their opinion.

Jill: Don’t be so quick to judge someone because of the political sign in their yard.

Write to Clare Ansberry at clare.ansberry@wsj.com

Thursday, October 15, 2020

Marin’s Estimated Housing Quotas Are Off The Chart! (Especially Marinwood)

Warning Marinwood!

Marin’s Estimated Housing Quotas Are Off The Chart!

Posted by: Sharon Rushton - October 14, 2020 - 4:13pmA series of erroneous state and regional policy and planning decisions, some of which were pushed by Big Real Estate and Big Tech, have culminated in the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) being on the brink of assigning unprecedented, exorbitant, unrealistic and flawed housing quotas to Marin County and its 11 municipalities. These housing quotas, known as Regional Housing Need Allocations (RHNA), are off the chart!

The Regional Housing Need Allocation (RHNA) is the state-mandated process to identify the total number of housing units each jurisdiction must accommodate. As part of this process, the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) calculates the total housing need (referred to as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment) for each planning region, including the San Francisco Bay Area, for an eight-year period. Then, each region’s planning agency, including the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), distributes this need to local governments.

On October 15th, the Association of Bay Area Government Executive Board will decide whether or not to adopt “Option 8A” as the allocation methodology to determine the Regional Housing Need Allocations (RHNA) (AKA Housing Quotas) for jurisdictions throughout the Bay Area.

If the Board adopts this allocation methodology (Option 8A), then the Estimated Marin County RHNA (2024-2032) would be 14,210 housing units. This is more than the current number of homes in Sausalito and Mill Valley combined! Due to new laws, this means that Marin County jurisdictions would need to not only identify sites (and adjust zoning on those sites) for over 14,000 homes but, in addition, ensure that new housing is actually constructed on the sites, all within the 8-year RHNA cycle. An absolutely impossible task!

Marin's total estimated housing allocation of over 14k units for the 2024-2032 RHNA cycle is over 6 times as large as that for the last 2015-2023 cycle, which was 2,298 units. For some individual jurisdictions, it's even worse. Unincorporated Marin’s new housing quota of 3,830 units is 20 times larger than that for the last RHNA cycle, which was 185 units.

Please review the below charts. The first chart (CHART 1) shows the final Marin County Regional Housing Needs Allocations for the 2015 to 2023 planning period. The second chart (CHART 2) demonstrates a rough estimate of the Marin County Regional Housing Need Allocations for 2024 to 2032, if the Option 8A Allocation Methodology is adopted and if the HCD RHNA Allocation Approach, the Plan Bay Area 2050 Regional Growth Forecast and the “High Opportunity Areas Map” methodology are maintained.

CHART 1: Marin County Regional Housing Need Allocation, 2015-2023

CHART 2: Rough Estimate of Marin County Regional Housing Needs Allocations, 2024-2032

TOTAL 14,210

These estimated housing quotas are completely devoid of credibility, based on Marin’s historic population growth and respected forecasts of Marin’s future population and job growth.

Marin County’s Historic Population Growth Rate:

Marin’s population growth rate has been negative for the last five years. From 2016 through 2020, the growth rate has ranged from -.02% to -.35%. Please see the below chart [1]:

Forecast of Marin County’s Population Growth by the California Department of Finance:

The California Department of Finance forecasts are highly respected and used by most public agencies. The Department of Finance estimates that Marin County’s current population (YR 2020) is 260,800 residents and projects that at the beginning of the next RHNA cycle (YR 2024) our population will be 259,362 residents. Therefore, the Department predicts that Marin’s population will shrink by 1,438 residents by 2024.

Furthermore, the Department of Finance projects that, between 2024 to 2032 (the next 8-year RHNA cycle), Marin County’s population will grow from 259,362 people (YR 2024) to 259,591 people (YR 2032), which is an increase of only 241 more people. [2] [3]

A growth of 241 people doesn’t even replace the 1,438 residents lost between YR 2020 and YR 2024. Hence, at the end of the next RHNA cycle (YR 2032), we will have fewer residents than we do now. This does not translate into a need for a tremendous amount of new housing.

Marin County Job Growth: Per the 2019 Marin County Economic Forecast by the California Department of Transportation; “Job growth in Marin County is slowing and will slow further during the forecast period. Marin County is at risk of losing jobs by 2020 or 2021.”[4]

The above historic population growth rates and the population and job growth forecasts by the Department of Finance and the Department of Transportation demonstrate that the estimated 2024-2032 Marin County housing quotas are far from realistic.

Not only is the Option 8A RHNA Allocation Methodology untenable because of the sheer magnitude of the resulting housing quotas, but, in addition, the methodology is unsound because of where it targets housing growth. Most of the targeted areas in Marin are distant from employment and high-quality public transit, which if developed, would lead to new residents using vehicles for their transportation needs, thereby increasing Green House Gas emissions. Tackling climate change is overlooked.

In addition, many (or most) of the targeted locations are hazardous. These include areas subject to high fire hazards, unsafe evacuation routes, toxic contaminants, sea level rise, flooding, high seismic activity, and high traffic congestion. When trying to improve housing equity, it is unconscionable to expose vulnerable senior and lower income households to high hazard risks, when they have the least resources available to cope with the adversity caused by such hazards.

Perhaps the most important point of all is Marin County’s potential growth is greatly constrained by our limited water supply.

The 2007 Marin Countywide Plan’s Environmental Impact Report (EIR) examined the cities’ and county’s zoning designations and projected potential growth of 14,043 more housing units. This didn’t include density bonuses. Alarmingly, the EIR concluded that “land uses and development consistent with the plan would result in 42 significant unavoidable adverse impacts”, including worse traffic congestion and insufficient water supplies.

The total estimated RHNA (2024 to 2032) for all of Marin is 14,210 housing units. This is similar to the number of housing units (14,043 units) evaluated by the 2007 Marin Countywide Plan’s EIR. Marin’s water supply is insufficient for this magnitude of growth.

In summary, Marin County lacks developable land, has very poor public transit, is encumbered with many environmental hazards and constraints, including a very limited water supply, and has a rapidly growing senior population who will soon retire and contribute to lower employment levels. These factors stunt population, business, and household growth. Respected forecasts confirm that Marin’s population and job growth, and therefore the need for housing growth, will remain flat or decline.

ABAG's RHNA Allocation Methodology and subsequently Marin’s RHNA allocations should be altered to reflect these important factors.

WHAT CAUSED THE HOUSING QUOTA DEBACLE?

A series of erroneous state and regional policy and planning decisions, some of which were pushed by Big Real Estate and Big Tech, have culminated in unrealistic estimated housing allocations for Marin and other jurisdictions throughout the Bay Area.

The Stakeholders

To begin this discussion of “What Went Wrong?”, it’s worth looking at the Stakeholders who are members of the ABAG Housing Methodology Committee. This is the committee that oversaw the creation of the Option 8A RHNA Allocation Methodology and recommended it to the rest of ABAG.

The ABAG Housing Methodology Committee consists of 9 Elected Officials, 12 Staff, 1 Representative from the CA Dept. of Housing & Community Development (HCD), and 16 Stakeholders. The Stakeholders make up 42% of the committee. 14 of the Stakeholders (37% of the methodology committee) are affiliated with housing developers, the building industry, housing advocacy organizations, or transit-oriented-development advocacy groups. The other two Stakeholders are an environmental attorney, who is also an Associate Director at the San Francisco State University, and an executive at La Clinica de la Raza, which is a community health center. There isn’t a single Stakeholder from an environmental or sustainable-slow-growth organization.

Here is a link to the “Housing Methodology Committee Member Bios”:

https://abag.ca.gov/sites/default/files/hmc_member_bios_01_2020.pdf

Flawed Forecasts & Maps

Besides other factors, the ABAG RHNA Allocation Methodology Option 8A incorporates: the Bay Area Regional Housing Need Assessment, which mandates 441,000 more units in the Bay Area by Year 2032; the Plan Bay Area 2050 Blueprint Regional Growth Forecast, which projects an increase of 1.4 million housing units by Year 2050; and the High Opportunity Areas Map, all of which are flawed.

Bay Area Regional Housing Need Assessment (RHNA) Is Exorbitant & Flawed

The California Department of Housing and Community Development assigned the Bay Area region an exorbitant housing need of 441,000 housing units.

As part of the RHNA process, the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) calculates the total housing need (referred to as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment) for each planning region, including the San Francisco Bay Area, for an eight-year period. Then, each region’s planning agency, including the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), distributes this need to local governments. If HCD’s methodology for calculating the total California Regional Housing Needs Assessment is flawed, then all subsequent housing needs for regions and local governments are similarly flawed. The Embarcadero Institute’s report proves that the HCD methodology is indeed defective.

The Embarcadero Institute’s report entitled; “Double Counting in the Latest Housing Needs Assessment” found that; “Senate Bill 828, co-sponsored by the Bay Area Council and Silicon Valley Leadership Group, and authored by Senator Scott Wiener in 2018, has inadvertently doubled the Regional Housing Needs Assessment in California.”

“Use of an incorrect vacancy rate and double counting, inspired by SB-828, caused the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) to exaggerate by more than 900,000 the units needed in SoCal, the Bay Area, and the Sacramento area.” [5]

It is important to note that Senate Bill 828 was authored by Senator Scott Wiener, who is heavily financed by Big Tech, Big Real Estate, and California Yimby.[6]

The Plan Bay Area 2050 Regional Growth Forecast Is Unrealistic

By law, the Regional Housing Need Allocation (RHNA) must be consistent with Plan Bay Area 2050. Yet, Plan Bay Area 2050’s Regional Growth Forecast is unrealistic.

The following Table 2 illustrates the approved Regional Growth Forecast for Plan Bay Area 2050 (supposedly integrating impacts from the COVIC-19 Pandemic & the 2020 Recession). Between 2015 and 2050, the region’s employment is projected to grow by 1.4 million to just over 5.4 million total jobs. Population is forecasted to grow by 2.7 million people to 10.3 million. This population will comprise over 4.0 million households, for an increase in nearly 1.3 million households from 2015.[7]

The following historic population growth rates, population growth projections, and historic housing production demonstrate that the Regional Growth Forecast for Plan Bay Area 2050 is misguided.

The California Department of Finance Bay Area Population Forecast:

The California Department of Finance projects that the Bay Area Region will consist of 9,112,910 people in YEAR 2050. [8] [9] This is 1,217,090 less people than the above Plan Bay Area 2050 projection.

California’s Historic Population Growth Rate:

California’s population growth rate is at a record low and predicted to remain low. Estimates released on Dec. 20, 2019 by the California Department of Finance show that between July 1, 2018 and July 1, 2019, the growth rate was just .35%, the lowest recorded growth rate since 1900. During the same time period, the Department reported that there was substantial negative domestic net migration, which resulted in a loss of 39,500 residents – “the first time since the 2010 census that California has had more people leaving the state than moving in from abroad or other states”.[10] Since 2019, we have entered into the COVID-19 recession, which should further lower California’s growth rate.

Historic Versus Projected Housing Production:

Figure 6 (below) illustrates historic housing production and Plan Bay Area 2050’s projected housing production, based on the plan’s anticipated demand for housing units. The plan projects an increase of 1.4 million housing units through 2050. The extreme difference between historic and projected production implies that the plan’s anticipated housing demand is over-exaggerated.

The above historic population growth, forecasted future population growth, and historic housing production demonstrate that the Plan Bay Area 2050 Regional Growth Forecast is unrealistic.

The “High Opportunity Areas Map” is Flawed

The Option 8A Allocation Methodology targets 70% of RHNAs for Very Low and Low households and 40% of RHNAs for Moderate and Above Moderate Units in “High Opportunity Areas”.

Here is the link to the map of "High Opportunity Areas" across California. You can zoom into Marin:

https://belonging.berkeley.edu/tcac-opportunity-map-2020

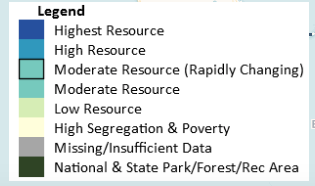

Below is a map of the “High Opportunity Areas” in Marin County.

Marin County High Opportunity Areas Map

However, the methodology for determining the “High Opportunity Areas Map” is flawed. Moreover, it appears that the Task Force, which created and oversees the Map, does not have accurate information about local characteristics. As a result, areas, which the methodology is supposed to exclude from development, are still being targeted with growth.

In February 2017, The California Fair Housing Task Force (Task Force) was created by the CA Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) and the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee. HCD and TCAC charged the Task Force with creating an opportunity map to further fair housing and “identify areas in every region of the state whose characteristics have been shown by research to support positive economic, educational, and health outcomes for low-income families - particularly long-term outcomes for children.”[11]

"High Opportunity Areas" are supposed to be areas with high quality public schools, proximity to well-paying jobs, a high-income population, and a clean and safe environment.

However, the Task Force’s methodology for creating the High Opportunity Areas Map fails to fulfill the requirement that the areas be healthy, clean and safe.

The report entitled; “California Fair Housing Task Force Methodology for the 2020 TCAC/HCD Opportunity Map – June 2020” [12] states that the map of “High Opportunity Areas” takes into account the following indicators, measures, and data sources:

Poverty (Percent of population with income above 200% of federal poverty line);

Adult Education (Percent of adults with a BA or above);

Employment (Percent of adults aged 20 to 64 who are employed in the civilian labor force or in the armed forces);Job Proximity (Proximity to low wage jobs filled by workers with less than a BA);

Median Home Value (Value of owner-occupied units);

Pollution Indicators “CalEnviroScreen 3.0 Indicators” (Exposure to traffic density and toxic contaminants in ground, air or water);

Math Proficiency (Percentage of 4th graders who meet or exceed math proficiency standards);

Reading Proficiency (Percentage of 4th graders who meet or exceed literacy standards);

High School Graduation Rates (Percentage of high school cohort that graduated on time);

Student Poverty Rate (Percent of students not receiving free or reduced-price lunch);

Poverty (Tracts with at least 30% of the population falling under the federal poverty line);

Racial Segregation (Tracts with a racial Location Quotient of higher than 1.25 for minorities).

According to the above list of data sources, the only public health and safety concerns that the methodology takes into account are traffic density and toxic contaminants in ground, air, or water. The methodology fails to consider the perils of areas subject to high fire hazards, unsafe evacuation routes, sea level rise, flooding, and high seismic activity,

It is worth repeating… When trying to improve housing equity and further fair housing, it is unconscionable to expose vulnerable senior and lower income households to high hazard risks, when they have the least resources available to cope with the adversity caused by such hazards.

Moreover, if you look at the “High Opportunity Areas Map” for Marin County, you will see that many of the locations with high traffic density and unsafe toxic contaminants are designated “High Opportunity Areas”, even though the methodology supposedly excludes such unsafe areas from growth. Therefore, it is assumed that the Map creators don’t have accurate information about Marin.

Other Problems with the Option 8A RHNA Allocation Methodology

By law, The Regional Housing Needs Allocations (RHNA allocations) must meet the five statutory objectives of RHNA[13] and be consistent with the forecasted development pattern of Plan Bay Area 2050. Yet, the Option 8A RHNA Allocation Methodology fails to fulfill the following RHNA statutory objectives and Plan Bay Area 2050 Draft Blueprint purpose, guiding principle, objectives, strategies, and policy:

The Second Statutory Objective for RHNA is; “Promoting infill development and socioeconomic equity, the protection of environmental and agricultural resources, the encouragement of efficient development patterns, and the achievement of the region’s greenhouse gas reductions targets provided by the State Air Resources Board pursuant to Section 65080.”[14]

The Sixth Statutory Objective for RHNA, pending state legislation, is; “Reducing development pressure within very high fire risk areas.”[15]

As mandated by Senate Bill 375, the main purpose of the Plan Bay Area 2050 Draft Blueprint, the Bay Area’s Sustainable Communities Strategy, is to lower Green House Gas (GHG) emissions from cars and light trucks while accommodating all needed housing growth within the region.

The Plan Bay Area 2050’s Guiding Principle entitled “Healthy” states; “The region’s natural resources, open space, clean water, and clean air are conserved – the region actively reduces it’s environmental footprint and protects residents from environmental impacts.”[16]

Plan Bay Area 2050 Strategy #8 states; “Reduce Risks from Hazards. Adapt the vast majority of the Bay Area’s shoreline to sea level to protect existing communities and infrastructure, while providing means-based financial support to retrofit aging homes.”[17] Until communities and infrastructure are actually protected from sea level rise, areas subject to sea level rise should not be further developed.

Plan Bay Area 2050 Strategy #9 states; “Reduce Environmental Impacts. Maintain the region’s existing urban growth boundaries through 2050, while simultaneously partnering with public and non-profit entities to protect high-value conservation lands. Further expand the Climate Initiatives Program to drive down greenhouse gas emissions.”[18]

The Plan Bay Area 2050 – Draft Blueprint states that Areas Outside Urban Growth Boundaries (including Priority Conservation Areas – PCAs) and Unmitigated High Hazard Areas should be protected.[19] As such, growth should not be targeted in such areas.

Contrary to the above RHNA and Plan Bay Area 2050 objectives, the Option 8A RHNA Allocation Methodology will not further Green House Gas reduction goals or protect residents from hazardous environmental impacts. Option 8A allocates too many housing units to suburban areas that are far from job centers, lack adequate public transit, and are subject to perilous hazards. Especially worrisome is the fact that the methodology increases development in high fire hazard zones with unsafe evacuation routes, and in areas subject to lack of water supply, sea level rise, and flooding.

------

The State’s (HCD's) and the Bay Area regional agencies’ (ABAG’s & MTC’s) approaches to determining the housing need must be defensible and reproducible for cities and counties to be held accountable. Unfortunately, the State and the Bay Area regional agencies are falling far short in this regard.

During the last Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) cycle (2015-2023), over 400 of California’s 480 municipalities have not reached their RHNA targets. New laws require local jurisdictions to not only identify RHNA sites but, in addition, to ensure that new housing is actually constructed on the sites. Yet, local governments are not developers and cannot force private property owners to build housing units. Indeed, the Embarcadero Institute found that the shortage of housing resulted not from a failure by cities to issue housing permits, but rather a failure by the state to fund and support affordable housing.

Moreover, non-performance in a RHNA income category triggers a streamlined approval process per Senate Bill 35 (2017), which lessens local communities’ control over land use, environmental protections, and quality development.

By issuing such inflated 2024-2032 allocations without providing funds for affordable housing, the State and Regional Agencies are setting local governments up to fail again.

[1] https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-counties/ca/marin-county-population

[2] http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/projections/documents/P1_County_1yr.xlsx

[3] http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/Projections/

[4] https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/transportation-planning/documents/socioeconomic-forecasts/2019-pdf/marinfinal-a11y.pdf

[5] https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.65/r3g.8a0.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Double-counting-in-the-Latest-Housing-Needs-Assessment-Sept-Update.pdf

[6] https://www.housinghumanright.org/inside-game-california-yimby-scott-wiener-and-big-tech-troubling-housing-push/

[7] https://www.planbayarea.org/sites/default/files/pdfs_referenced/Plan_Bay_Area_2050_-_Regional_Growth_Forecast_July_2020v2DV_0.pdf

[8] http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/projections/documents/P1_County_1yr.xlsx

[9] http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/Projections/

[10] https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-12-21/california-population-continues-to-decline-with-state-emigration-a-major-factor

[11] https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/ctcac/opportunity/2020-tcac-hcd-methodology.pdf

[12] https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/ctcac/opportunity/2020-tcac-hcd-methodology.pdf

[13] https://rhna-factors.mtcanalytics.org/data/RHNA_Statutory_Objectives.pdf

[14] https://rhna-factors.mtcanalytics.org/data/RHNA_Statutory_Objectives.pdf

[15] https://rhna-factors.mtcanalytics.org/data/RHNA_Statutory_Objectives.pdf

[16] https://www.planbayarea.org/sites/default/files/PBA2050_GP_Res.4393_Table.pdf

[17] https://www.planbayarea.org/sites/default/files/5b_PBA50_DraftBlueprint_StrategiesAction.pdf

[18] https://www.planbayarea.org/sites/default/files/5b_PBA50_DraftBlueprint_StrategiesAction.pdf

[19] Mayor Pro Tem Pat Eklund. “Report on ABAG to MCCMC”. September, 2020

Tuesday, October 6, 2020

Monday, October 5, 2020

Marinwood housing will surge with Low Income housing with new Plan.

Marin County and its 11 municipalities will be required to adjust their zoning to allow much more housing, particularly for low-income residents, if policies in the works at the Association of Bay Area Governments are adopted.

The association, a regional planning agency governed by representatives from the Bay Area’s nine counties and 101 cities and towns, approved a final blueprint last month for Plan Bay Area 2050.

Updated every four years, Plan Bay Area integrates transportation, land use and housing to meet greenhouse gas reduction targets set by the California Air Resources Board. In an effort to address concerns about racial equity, the latest iteration of the plan also identifies “high resource areas” near public transit where it recommends that increased housing development should be promoted.

Areas within Novato, San Anselmo, Corte Madera and unincorporated parts of Marin fall into this category. Discussion regarding possible policies to implement this strategy have not begun.

““We’re not at that point yet,” said Matt Maloney, director of regional planning for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission. “We will likely be taking that up next year.”

In the meantime, however, ABAG’s housing methodology committee approved a plan last week for deciding how many homes counties and municipalities should be required to plan for from 2023 to 2031.

Every eight years, the state Department of Housing and Community Development projects how much new housing will needed in the Bay Area to accommodate expected population and job growth. ABAG then decides how many of those homes to assign to each county and municipality in the Bay Area. Local jurisdictions are required to adjust their zoning laws to help make the creation of that amount of housing possible.

The methodology approved by the committee last week is aligned with the high resource area strategy contained in the Plan Bay Area 2050 blueprint. It would assign more of the very low- and low-income homes to counties and municipalities containing higher concentrations of “high opportunity areas.”

“Those are essentially the high resource areas,” Maloney said. “It’s synonymous with that term.”

“That includes most of Marin,” said Novato Councilwoman Pat Eklund, one of the few ABAG board members to vote against the methodology.

According to an ABAG staff report, the “high opportunity area” methodology approach seeks to “affirmatively further fair housing by increasing access to opportunity and replacing segregated living patterns.”

A committee convened by the California Department of Housing and Community Development and the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee developed the map of high resource/opportunity areas in use. The designated areas contain amenities associated with childhood development and economic mobility such as low poverty rates and high educational attainment, employment rates, home values and school test scores.

Marin’s share of the housing assignments amounts to only 1%. Under the new methodology, however, that share would triple to 3%, while Alameda County’s share would be reduced from 23% to 19%, and Contra Costa County’s share would drop from 11% to 10%.

Eklund said the impact of the percentage increase is magnified because the assignment total is more than doubling. In the current 2015-2023 cycle, the nine Bay Area counties had to plan for 187,990 residences. In the 2023-31 cycle, they will have to adjust their policies to accommodate 441,176 residences.

If the allocation procedure approved last week is adopted by the ABAG executive board later this month, Marin could see the number of residences assigned to them increase from 2,298 in the 2015-2023 cycle to 14,210 in the 2023-31 cycle.

For example, Belvedere would be required to plan for 160 new residences, half of which would have to be affordable for people with low-income status. In the current cycle, Belvedere had to plan for 16 residences.

Eklund said she disagrees with the ABAG committee’s decision to include the number of existing households in a jurisdiction, together with the number of households expected to be added over the next several decades, when projecting the need for new housing.

“To be straightforward, the legal requirements for housing elements have changed a lot since the last cycle,” said Daniel Saver, MTC’s assistant director for housing and local planning. “It is going to be much harder for local jurisdictions to adopt compliant housing elements this time around.”

Failure to do so, however, could prove costly. Assembly Bill 101, which became effective at the end of July 2019, authorizes the state attorney general to sue jurisdictions and fines ranging from $10,000 to $600,000 per month.

Supervisor Damon Connolly, Marin County’s representative on MTC, wrote in an email that he is concerned about the methodology and will work with local ABAG representatives to “push back and raise areas of concern.”

“For example, the 22x increase in the allocation for unincorporated Marin is startling,” Connolly wrote. “The methodology appears to emphasize ‘high resource areas’ without regard to proximity to jobs or high quality transit or other constraints.”

Supervisor Dennis Rodoni, who represents Marin County on the ABAG board, wrote in an email that the county needs to make sure that “unincorporated areas without infrastructure and good transit do not get over allocated, forcing density to outside city boundaries and more suburban areas.”

“This will be a challenge,” Rodoni added, “as most of the Bay Area is currently embracing the methodology for these allocations and many of our local opinions are in the minority.”

Saver said the path that ABAG is following is dictated by state law. For example, he said the 441,176 assignment total came from the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development.

Saver said the big increase in the number of units assigned is due to state Sen. Scott Wiener’s Senate Bill 828, passed in 2018. The law allows the state to take into account existing housing needs as well as projected future need when determining the number of housing assignments.

In 2016, management consultant McKinsey and Co. projected that California needed to create 3.5 million more homes by the middle of the next decade.

Saver said the incorporation of “high resource/opportunity areas” into Plan Bay Area’s equation is required because of Assembly Bill 686, which mandated that counties and cities implement the Obama-era policy of “affirmatively furthering fair housing.”

For decades, housing in the United States was segregated by race. The Federal Housing Administration financed the building of suburban subdivisions during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, but lent the money to builders on the condition that they not sell any of the new houses to African-Americans.

Saver said the state law remains in effect despite the fact that the Department of Housing and Urban Development, under the direction of Trump appointee Ben Carson, scrapped the policy at the federal level earlier this summer.

Saver said the state has allocated millions of dollars to help local jurisdictions comply with the loftier planning goals.

“We certainly hope that all of our local jurisdictions are able to adopt compliant housing elements, and we’re going to put resources into helping them get there,” he said. “It will be a big lift.”