She handed a stranger $2,220 cash in a paper bag. Her reward: a BART parking spot

Rachel Swan Jan. 24, 2019 Updated: Jan. 24, 2019 1:19 p.m.

1of2Joy Hoffmann paid $2,220 cash for another BART rider’s permit to park in the Lafayette Station lot until she got a space in S.F.Photo: Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle

1of2Joy Hoffmann paid $2,220 cash for another BART rider’s permit to park in the Lafayette Station lot until she got a space in S.F.Photo: Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle2of2The Lafayette BART Station parking lot fills early, as do most other lots in the system — 7 a.m. in this case, some even earlier.Photo: Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle

It was like a drug deal.

Once a year, Joy Hoffmann would arrive at a Safeway parking lot next to the Lafayette BART Station clutching a paper bag with $2,220 cash. A white car would be idling there, with a woman waiting inside. Hoffmann would furtively hand over the bag, and the woman would give her a plastic tag to hang in her car windshield: 12 months of permitted parking at BART.

“And then I’d be jumping up and down,” said Hoffmann, a financial worker in Moraga who rode BART for 20 years from Lafayette to downtown San Francisco. She paid a huge markup for the permit — $185 a month, compared with BART’s fee of $105 — but the price was worth it. Before she stumbled on the subletting scheme, Hoffmann was among thousands of commuters marooned on a waiting list that never seemed to budge.

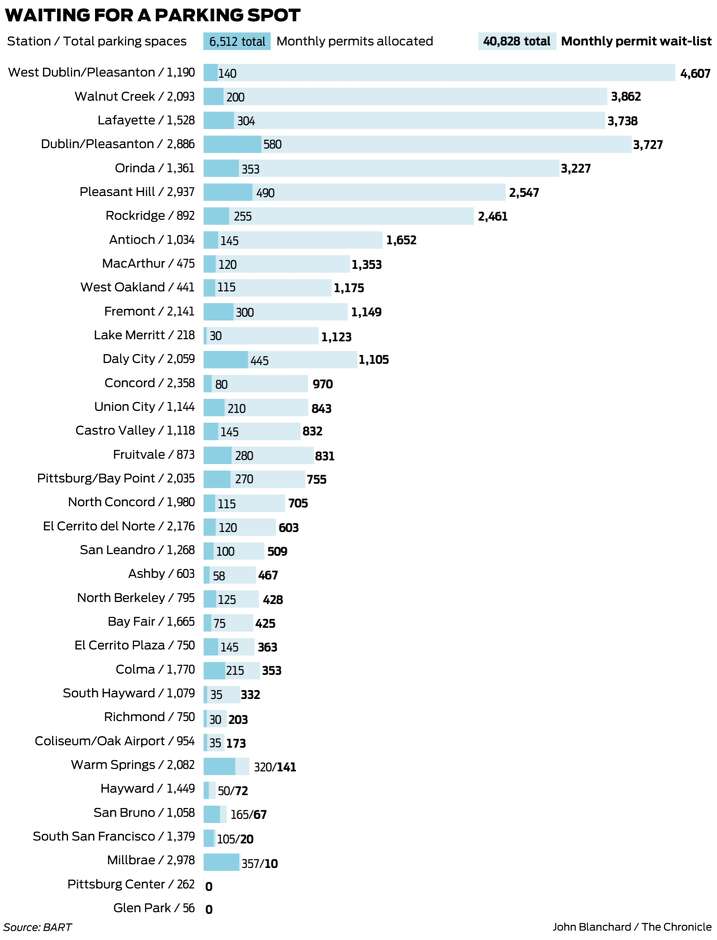

Today, the list of applicants is just shy of 41,000 people for 6,512 monthly parking spots scattered throughout the BART system. Board directors will discuss the crunch during an intensive two-day workshop that starts Thursday, where parking likely will emerge as a contentious issue.

“We’re seeing this shift to thinking about climate change, greenhouse gases, that we should eliminate cars,” said board Director Debora Allen. Her district spreads through the hills and flatlands of central Contra Costa County, where driving is essential to daily life.

The car-free vision works in San Francisco, which has robust alternatives to get from Point A to Point B, Allen said. But in suburban areas where housing is sprawled out and buses are scarce, commuters are out of luck.

BART’s numbers show that parking permit demand is highest in the suburbs. At West Dublin/Pleasanton Station, 4,607 people are lined up for 140 permitted spaces. Walnut Creek has 3,862 people jockeying for 200 monthly permit spots. And in Lafayette, 3,738 people linger on a wait-list for 304 monthly permits, at a station that draws commuters from as far away as Dixon and Davis (Yolo County).

Those conditions opened the door for gray market trading, which came as no surprise to some board directors, riders and city officials who are pressing for more parking. They say the situation will only get worse when BART starts filling its lots with housing under a state law enacted last year.

“BART could care less about parking,” said Lafayette Mayor Cameron Burks. He opposed the law, arguing that dense development at BART stations — without any requirement for a garage or parking structure — will only put more cars on the road. When people circle a parking lot and can’t find any space, they wind up on the freeway, Burks and others said.

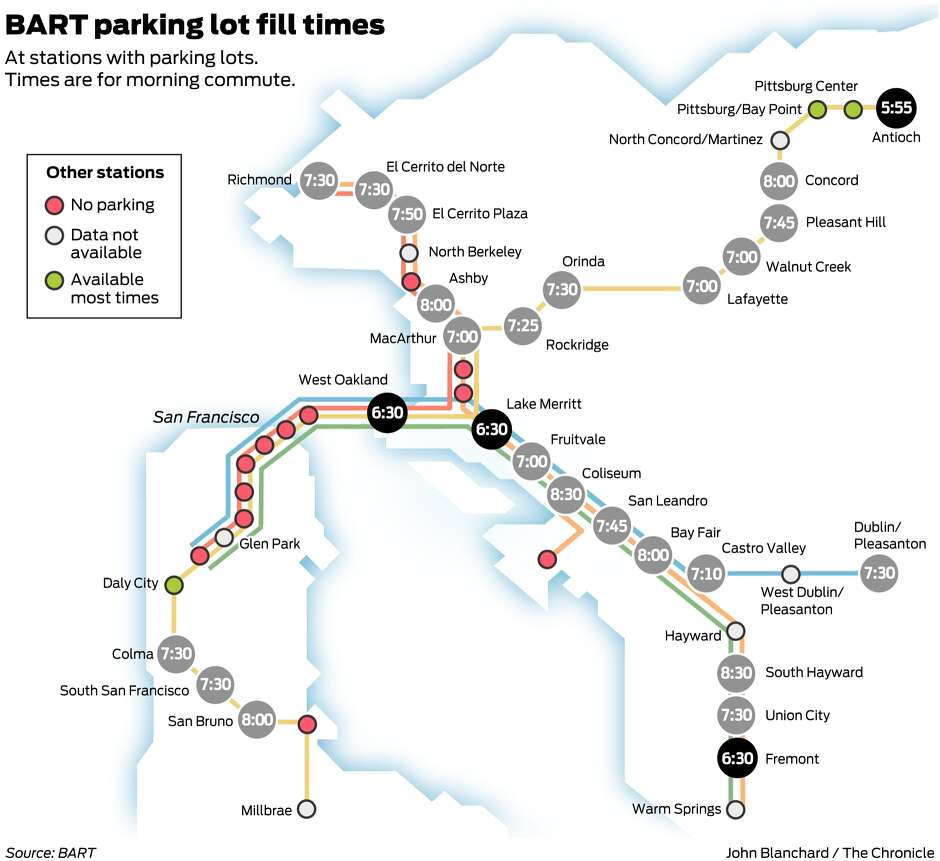

BART also sets aside one-day permitted spots for people who reserve them in advance, and spaces for travelers seeking to stow their cars for several days. The vast majority of BART’s nearly 50,000 parking spaces are not reserved, and at most stations they fill up by 7:30 a.m. on weekdays.

After 10 a.m. anyone can park in permitted spots, which doesn’t help people who have to be at work hours earlier, Allen said.

The issue has created an ideological split among BART riders. Some cling to the concept that shaped BART back in 1972: suburban stations with vast parking lots that guaranteed a space for every commuter. But others see those lots as prime space for apartments, plazas and town houses — a form of urban design that would wean people off cars and reduce carbon emissions.

“If we stopped subsidizing housing for cars, we’d have enough money to subsidize housing for people,” said Jeffrey Tumlin, a principal at the San Francisco transportation consulting firm Nelson\Nygaard. “And then people wouldn’t need to drive.”

Fear of parking scarcity has made the monthly permits a valuable and sought-after commodity.

Lark Hilliard, who lives in Orinda and got a permit several years ago, said she still hangs on to it even though she no longer rides BART every day.

“I knew I’d never get it again,” she said.

That sentiment appears to be widespread. Permit turnover has been slow, said Bob Franklin, department manager of customer access and accessibility at BART. In December, he said, the agency issued just 136 permits, barely chipping away at its long queue. Anecdotally, people wait as long as two years to get a spot.

Subletting permits is against the rules, but that hasn’t stopped people from doing it. Since 2016, BART officials caught at least five permit holders who advertised on Craigslist or NextDoor, Franklin said.

“Other people on the wait-list see that and call it to our attention,” he said. “They don’t appreciate it.”

He also recalled three instances in the past three years of people putting fake parking placards in their windows.

Joy Hoffmann at the Lafayette BART Station parking lot where she used to pay a premium to a permit holder for use of their tag.

Photo: Photos by Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle

Hoffmann said she found her dealer by posting a desperate plea on an internet discussion board. The exchange was somewhat complicated — besides paying cash in a paper bag, Hoffmann also had to give the woman her license plate number so it could be linked to the tag — but it worked for three years. Then, in 2017, Hoffmann snagged a parking space at a private lot through her job.

She urges BART to adopt a more equitable permit strategy, with incentives for people to give up their spaces.

“This is like people who sublet apartments in New York when they have rent control,” Hoffmann said. “It’s the same model.”

One solution that’s not on the table: more parking. BART doesn’t have land or money to build new structures or lots, which cost $20,000 to $30,000 a space. The planned surface lot at Antioch Station, scheduled to open next year with 850 spaces at a cost of $16.4 million, will likely be BART’s last parking expansion.

Instead, the agency will focus on modernizing its carpool program so that people who share a vehicle can be guaranteed a spot. Board directors will also discuss new enforcement tools, such as license plate readers, which could free up police while clamping down on underground trading.

Board Director Lateefah Simon, whose district stretches from Richmond to downtown San Francisco, said she gained a new perspective on suburban commuting last August, when she moved from West Oakland to North Richmond.

Simon doesn’t drive, so she takes Uber or Lyft to Richmond BART each morning.

“A bus to BART would take 45 minutes, and as a single mom with multiple jobs, I don’t have that kind of time,” Simon said. “I now understand in a different way the complexities of why people need a place to park.”

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com

No comments:

Post a Comment