A new study challenges some widely held assumptions about urban and suburban development.

Sprawl is not sustainable. That’s the basic assumption shaping high-rises, infill developments, and master plans in cities around the world—not to mention a guiding principle of this publication.

But a new report by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat challenges one of the central tenets of urbanism from a few unexpected angles. Comparing the daily patterns household-to-household, researchers found that certain transportation habits and overall energy use can be more environmentally efficient in suburban housing than residential high-rises.

To date, most research into urban sustainability—in terms of, say, gasoline guzzled, miles traveled, and water, heat and electricity consumption—has not examined household data in such granular detail. Studies that have generally concluded that suburbs are less efficient “are not building studies, but urban scale studies,” said Antony Wood, the executive director of the CTBUH and research professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s College of Architecture. “It’s urban Chicago versus total Chicago.”

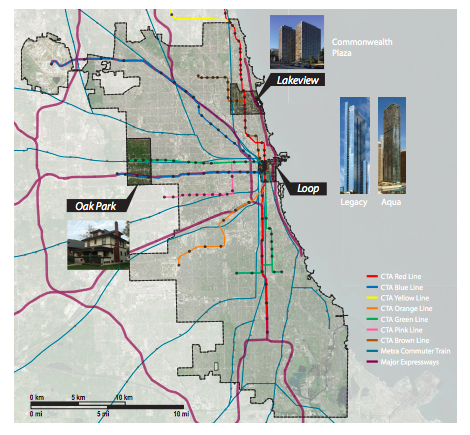

Wood and co-author, Peng Du, who is also a professor at IIT’s College of Architecture, wanted to capture more nuance than that. They created a survey comparing transportation patterns, energy consumption, and use of public space, which they administered to 249 households in four downtown Chicago high-rises and 273 single-family homes in Oak Park, a historic residential neighborhood. Over three months in 2014, respondents answered detailed questionnaires about their daily habits, and submitted 12 months worth of utility bills.

Wood and Du found many points of affirmation that urban life is indeed more sustainable. High-rise dwellers traveled more on public transit, walked and biked more, and made more efficient use of outdoor public space—no surprise there, since they lived closer to CTA stops, parks, and walkable amenities. The researchers also added up all the roads, water pipes, sewage lines, power and electricity supply required to serve the two types of households, and, glaringly, found that suburban development required roughly eight times more “infrastructure network length” per person than the downtown high rises.

Score one for dense urban development, right?

Overall, yes. But the details get more interesting. The building industry often assumes that suburban single-family homes require more energy to heat, light, and cool, since they have larger surface-to-volume ratios than smaller apartment units. But on a per-person basis, Wood and Du found that high-rise residents actually consumed about 27 percent more energy. On a per-floor area basis, probably because of all the shared hallways, elevators, gymnasiums, and lobbies, the downtown towers still consumed about 5 percent more energy than the suburban homes. Comparing travel habits, Wood and Du also unexpectedly found that downtown households actually traveled more miles by car, total, every year. The high rises also had more parking spaces per capita than the suburban dwellings.

What’s going on here? Demographic differences between the two groups in the study probably explain the surprising results. The large suburban households of Oak Park were full of kids, while the apartment towers held childless young professionals and empty nesters. That means, at least in a given room, more people are using the same amount of energy. Similarly, a stuffed minivan is more energy efficient than a lone commuter. “Suburban households were much more likely to have children that they bring with them during car travel,” the report states, “while single high-rise residents took more solo trips.”

This study is limited, but also important, because of the level of data it uses. On the one hand, its scope is much too small to make any sweeping conclusions about urban-vs-suburban eco-friendliness around the country or the world. Eventually Wood and Du would like to take on a larger-scale version with many more families, buildings, and neighborhood shapes. On the other hand, this pilot study offers quantified evidence that demographics count when it comes to environmental efficiency. A new LEED-certified apartment building near the subway may not be very eco-friendly if it’s full of people with resource-intensive lifestyles, as so many luxury developments are. Likewise, don’t get too pious about families out in the unsustainable suburbs: In some ways, they may be living greener than you are.

No comments:

Post a Comment