Many years ago, a prominent man wrote to one of his favorite authors about his latest book. This man had been a soldier, a hunter, an athlete, an historian, and a social reformer, and was now employed in a post of some significant responsibility. He had many children, and was by all accounts a bluff and hearty father.

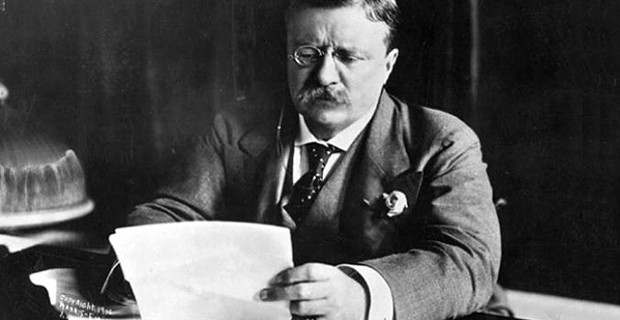

“My dear Mr. Grahame,” he wrote,My mind moves in ruts, as I suppose most minds do, and at first I could not reconcile myself to the change from the ever-delightful Harold and his associates, and so for some time I could not accept the toad, the mole, the water-rat, and the badger as substitutes. But after a while [my wife] and two of the boys, Kermit and Ted, all quite independently, got hold of The Wind Among the Willows [sic] and took such delight in it that I began to feel that I might have to revise my judgment. Then [she] read it aloud to the younger children, and I listened now and then. Now I have read it and reread it, and have come to accept the characters as old friends; and I am almost more fond of it than your previous books. Indeed, I feel about going to Africa very much as the sea-faring rat did when he almost made the water-rat wish to forsake everything and start wandering!And he closes with all good wishes, “Sincerely yours, Theodore Roosevelt.”

I felt I must give myself the pleasure of telling you how much we had all enjoyed your book.

Now that’s a letter from a different world.

It makes my gorge rise, after that breath of fresh air with the tang of the river in it, to have to utter the words “Common Core Curriculum,” and its relentless, contemptible, soul-cramping, story-killing, pseudo-sophisticated, utilitarian focus not on the beauty and truth and goodness that good art reveals, not on the imaginative worlds that good books can open up to someone simply willing to receive them as gifts on their own terms and enter into them with gratitude, but upon scrambling up supposed skills in suspicion, superficial criticism, and dissection.

Yet I have to do it. I hate the task, just as I’d hate to have to pull on rubber galoshes to clear out a clogged cesspool. But someone has to do it.

Let’s look at that letter again. It is written by the Theodore Roosevelt, who, whatever may be one’s opinion of his policies, was not only an immensely learned man. He was an immensely imaginative man; it comes across in all of his words and deeds. And he, President of the United States at that time (1904), did not write to praise Kenneth Grahame for helping his brood of children to “actively seek the wide, deep, and thoughtful engagement with high-quality literary and informational texts that builds knowledge, enlarges experience, and broadens worldviews.” I can imagine Teddy taking the birch switches down from the wall to give a thrashing to someone who could write such a dimwit sentence. For we do not read The Wind in the Willows in order to build knowledge about talking rats, or to broaden worldviews, whatever that term from political sloganeering is supposed to mean. We read The Wind in the Willows to enter the world of The Wind in the Willows, and maybe learn something about ourselves in the process. But the aim of reading the work is simply the joy and the wonder of it; it is a good book, because it tells us good and true things in an artful way.

Teddy did not praise Kenneth Grahame for helping the Roosevelt children to learn how to analyze what the CCC calls, with revealing ugliness and reductiveness, “text,” so that he would “reflexively demonstrate the cogent reasoning and use of evidence that is essential to both private deliberation and responsible citizenship in a democratic republic,” as if the noblest task of mankind was to listen to a political advertisement or to cast a vote. Teddy praised the man for giving him new friends: Toad of Toad-Hall, the Rat, the Mole, and the Badger. If you are not reading novels to make new friends, or to wander across the fields, or to sail the sea, then you should not read them at all.

And that, as it happens, is one of the very things you learn from The Wind in the Willows itself. When the story begins, the shy and pleasant Mole is invited to join the Rat in a boat. The Mole, being a Mole, hasn’t ever been in a boat before, and he finds it really quite nice, as he leans back and feels the swell of the water beneath him.

“Nice? It’s the only thing,” said the Water Rat solemnly, as he leant forward for his stroke. “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing around in boats. Simply messing,” he went on dreamily: “messing—about—in—boats.”

Is it too much to ask that teachers of young children remember, hidden somewhere underneath their encrustations of sin, false learning, ambition, treadmill-pumping, work for work’s sake, and jaded familiarity with the surfaces of things—underneath the calluses of adulthood—that the Rat is right, and that there is nothing, absolutely nothing, half so much worth doing as simply messing around in boats? I mean this. Is it too much to ask that teachers of young children remember that works of the imagination are for the soul? That our first response to them should be one of wonder and gratitude? And our second response, and our third?

The Common Corers get things exactly backwards. You do not read The Wind in the Willows so that you can gain some utilitarian skill for handling “text.” If anything, we want our children to gain a little bit of linguistic maturity so that they can read The Wind in the Willows. That is the aim. I want my college students to read Milton so that they can enter the world that Milton holds forth for us. I show them some of his techniques as an artist, since they’re mature enough to appreciate them, but not so that they can reduce the poem to an exercise in rhetoric. I show them those techniques so that they may understand and cherish the poem all the more. I want them to become “friends” with Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. I want them to climb with Dante and Virgil the glorious mountain of Purgatory. I want them to stand heart to heart with the Geats as they watch the flames devour the body of their deceased king Beowulf.

Those are the important things, the permanent things. If you are not reading The Wind in the Willows as Theodore and Edith Roosevelt and their children were reading it, then you should not read it at all. If you are turning Tom Sawyer into a linguistic exercise with a veneer of intellectual sophistication, then you should not read Tom Sawyer—in fact, you cannot have understood a blessed thing about Tom Sawyer. If you are reading The Jungle Book for any other reason than to enter the jungle with Mowgli, Bagheera, and Baloo, then you had best stay out of the world of art, keep to your little cubbyhole, cram yourself with pointless exercises preparatory for the SAT, a job at Microsoft, creature comforts, old age, and death.

But what baffles me most about this latest and hugely expensive exercise in inhumanity is that it has never been cheaper or easier (were it not for distractions and the insanity and moral squalor around us) to give children a splendid education in arts and letters. Back in 1904, books were still relatively expensive for most families. There were no paperbacks. You couldn’t order five or six used novels by Dickens for the price of a couple of pizzas. You couldn’t go to library book sales—dumping classics among the trash—and pick up a copy of The Wind in the Willows for the price of a candy bar.

There’s no excuse for us. Any school librarian with a free hand and a very modest amount of money can quickly put together a set of a thousand or two thousand classic novels and books of poetry fit for children, that would have been far beyond the means of almost anyone a hundred years ago. And what about the teachers? Let us not fall for educational patois and the unspoken assumption that it requires experts with special knowledge and secret recipes of twenty five herbs and spices to make children learn against their will. For the most important thing that any teacher of reading can do for children is to read good and great books with them and for them, with imagination and love. It is not like designing a rocket to go to the moon. It is at once far easier and far more profound than that. It is like silence, and play, and prayer. It is like messing around in boats.

The views expressed by the authors and editorial staff are not necessarily the views of

Sophia Institute, Holy Spirit College, or the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts.

Sophia Institute, Holy Spirit College, or the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts.

No comments:

Post a Comment