California Bill Would Allow Unrestricted Housing by Transit, Solve State Housing Crisis

Is this the best use for land around the Expo Line in Los Angeles?

Payton Chung via Flickr

San Francisco’s state senator, Scott Wiener, has introduced a bill that would all but abolish the city’s famously strict land use controls—and virtually every other residential zoning restriction in California’s urban neighborhoods. It’s just about the most radical attack on California’s affordability crisis you could imagine.

Wiener’s bill, SB-827, flies in the face of every assumption Americans have held about neighborhood politics and design for a century. It also makes intuitive sense. The bill would ensure that all new housing construction within a half-mile of a train station or a quarter-mile of a frequent bus route would not be subject to local regulations concerning size, height, number of apartments, restrictive design standards, or the provision of parking spaces. Because San Francisco is a relatively transit-rich area, this would up-zone virtually the entire city. But it would also apply to corridors in Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego, and low-rise, transit-oriented suburbs across the state. It would produce larger residential buildings around transit hubs, but just as importantly it would enable developers to build those buildings faster.

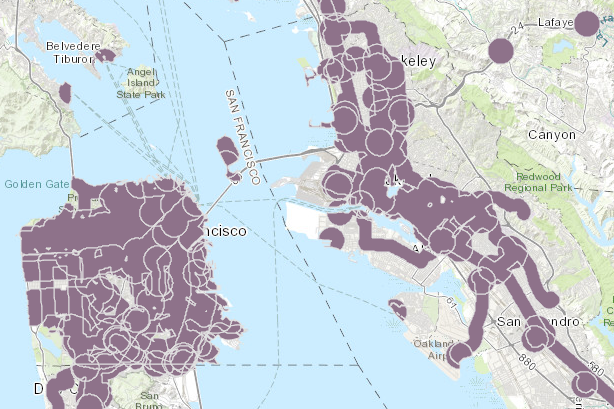

Purple areas correspond to “transit-rich” zones under Wiener’s bill.

Courtesy Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

Almost everyone agrees California needs more housing. The state is home to 6 of the country’s 10 most expensive metro areas, in part because of decades of under-building. New building permits are hard to come by thanks to balkanized power structures within and between cities, in addition to various structural incentives not to approve new housing units. Ironically, because transit access is an amenity people pay for and then hoard, even some areas around commuter rail or subway stops are required to hold only houses with big front yards.

Of course, transit hubs are exactly where more housing can be built with the least effect on traffic, so that’s the practice Wiener’s bill tries to promote. It would establish a minimum height (45 to 85 feet, depending on street with and distance) for new buildings sitting on the valuable land that abuts transit corridors. It would end parking minimums and pave the way for skyscrapers around every subway stop in California, and along many big avenues as well.

In a Medium post announcing SB-827, Wiener pointed to a McKinsey study that shows the tremendous potential of transit-oriented development in California. The state currently has 1.16 million housing units that can be considered transit-oriented. The law could open the door to as many as 3 million more.

At first glance, the bill is too radical to pass; California homeowners would revolt, or at least use their remaining local power to shut down a whole lot of bus routes. At least one advocate for equitable development in South L.A. has compared the bill to Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Like most attempts to build more housing, it will likely be crushed between homeowners seeking to preserve property values and renters fearful of the resultant tear-downs and evictions.

Still, it represents a reassuring trend in California politics: the rising tide in the statehouse to overwhelm local restrictions on housing construction. In September of 2016, for example, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law that eased the approval of accessory dwelling units, or granny flats, across the state. The result has been a bona fide housing boomlet in the backyards of cities like Los Angeles, whose byzantine permitting process had stymied would-be builders.

Wiener’s transit-oriented development bill, if it passed, would have the most radical impact of any California law since Prop 13, the 1978 resolution that permanently lowered the state’s property taxes (and dealt a blow to state finances that continues to this day). But even if it doesn’t, it puts some smaller good ideas on the table. If anyone were in a position to get some part of this passed, it would be California Gov. Jerry Brown, who is in the final year of his well-received second stint in charge of the country’s most populous state.

No comments:

Post a Comment